A pregnant teenager stands alone in a cinder-block cell in one image. In another, a young body shivers, curled up in an oversized T-shirt huddled in the far corner of a cold cement room.

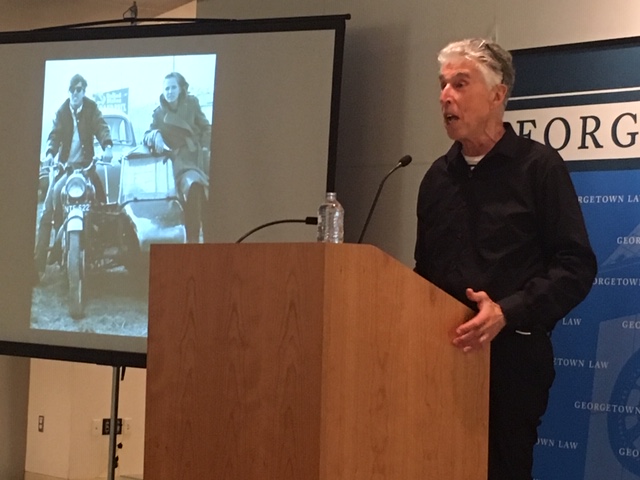

The pictures are just a few of the thousands in a collection by Richard Ross, who uses his photography as a vehicle to highlight the needs of the estimated 48,000 children in custody each day.

Ross has documented the lives of young people caught up in the juvenile justice system in Juvenile-in-Justice, a project he founded to connect human faces to a story often told in terms of cold statistics.

Ross has documented the lives of young people caught up in the juvenile justice system in Juvenile-in-Justice, a project he founded to connect human faces to a story often told in terms of cold statistics.

“My whole focus for the last 15 years has been interviewing these kids and being a co-conspirator with them in terms of trying to be the conduit for their voice,“ he said.

Ross was one of three juvenile justice experts on a webinar hosted Tuesday by the Dui Hua Foundation as part of a series focused on unique issues girls face when they come into conflict with the legal system.

Ross was joined by Michelle De Young, a social worker in the juvenile unit of the public defender’s office juvenile unit in San Francisco, and Kasie Lee, an assistant district attorney for the city and county of San Francisco.

A common thread was the power of storytelling to both inform and reform the juvenile justice system.

Ross has talked with more than 1,000 young people over the years, but he puts a special priority on amplifying the voices of those he’s visited in solitary, or isolation units.

“When you put a 10-year-old in a cell like this, and a steel door closes you can hear the sound, you can hear the cold and then four deadbolts are thrown across there, how much damage does it do to these kids? How do you imagine you’re doing something good?” Ross said, referring to an image of a child on the screen.

How to humanize cases

His images have been presented at congressional subcommittee hearings, as well as dozens of hearings on juvenile justice reform at the state and local level. They are stark indictments of a broken system.

The key to making reform a reality is not to just give faceless data, but to share a compelling story, with a human face, according to Ross.

“Any institution might say it’s an anomaly, a time-out room, it’s administrative segregation, any number of words, but when you put them all together — and I can do that in a compelling and artistic fashion — it pulls you in,” Ross said.

“It’s hard to see these kids as perpetrators of crimes when you realize how much they’re victims of crimes,” he said, adding that nearly all the young people he’s met with have been in need of mental health services.

Lee said she focuses on the individual stories and experiences of young people when deciding whether to press criminal charges against those accused of breaking the law. She knows her decision will be life-altering.

While accused of crimes themselves, many of the girls in her caseload are victims of commercial sexual exploitation of children, a category of crimes known as CSEC. For years, children in California were prosecuted for prostitution and other charges regardless of the abuse they’d suffered, Lee explained.

“The act of bringing them into the system, handcuffing them, putting them into these cells in juvenile hall with no windows, that really just retraumatized them,” Lee said, adding that California passed legislation in 2017 to prevent the charging of minors with prostitution and to allow more leniency for those charged with other crimes who have been victims of human trafficking.

‘Looking for safety’

In part, she credits those who listened to young people for that small success. Still, she said there is an enormous amount of work to be done.

“We often find that the mothers of these youth were also part of the dependency system, the child welfare system and that they were victims of abuse and neglect and abandonment — so this is part of a vicious cycle,” Lee said.

DeYoung, who works in the public defenders’ office to coordinate social services to teenage girls, said that reality can bring out challenging behavior.

“My youth test out everyone’s boundaries — not to rebel or to act out, but because they’re trying to find a solid wall, something they can identify and hold on to, something that makes sense and is always constant,” she said. “They’re looking for safety.”

Part of the key to doing that is having adults who will listen to and validate their stories, DeYoung said, adding that the young people also need coping skills.

“Most of my girls don’t know how to process their emotions or even know what they are,” DeYoung said. “Most of my girls can’t describe to you what being embarrassed, anxious, sad, happy or vulnerable feels like. When we ask, they say they’re irritated or angry — those are the only emotions they know and are easiest to feel. That’s how they’ve survived.”

While DeYoung’s priority is to keep the girls she works with out of locked facilities, Ross’ goal for more than a decade has been to get himself inside.

“My role is to get into these places, which takes endless emails, endless phone calls, endless who-knows-who. I wear a journalist hat, I wear a professorial hat, I do anything possible, and I am relentless,” Ross said.

“Once you get in there, you have to very quickly develop trust with the kid, and I do that by knocking on the door, taking off my shoes, asking for permission, and sitting on the floor and giving these kids power over me,” Ross said.

He is keenly aware that children of color are disproportionately represented in the system, but makes it a point to include portraits of white girls in his work because policymakers are predominantly white men.

“I want to have an image like this so they can identify and say ‘Maybe we should do something like this because she looks familiar in terms of my own family, my own community, my own church, my own school, so I can’t dismiss it as the ‘other,’” Ross said, referring to an image of a white teen.

All of his work emphasizes simplicity. A photo, few words of text and audio with the child’s own voice has the power to reach everyone from policymakers to high school students, Ross said, pointing out that high school students are the policymakers of the future.

“Simple, simple stories, simple data. I need to have this information repeatable for it to have an effect,” Ross said. “The power of the voice, the power of telling the story from their own experience — I want these things to haunt you.”

► See Ross’ work on our sister site, Juvenile Justice Information Exchange,

Richard Ross: Juvenile Lifers

JJIE featured a series of photos and recordings by Richard Ross from his interviews of people sentenced as juveniles to life without parole. Some are now geriatric.

► For more information on juvenile justice issues and reform trends, visit the JJIE Resource Hub