AFTERSCHOOL ALLIANCE

AFTERSCHOOL ALLIANCE

The widening gap between rich and poor in America — even before the pandemic — is shown in a new report on children’s access to after-school programs.

A survey of 30,000 households in January through March 2020 by the Afterschool Alliance showed a large drop in the number of children attending after-school programs and showed that parents have less access to these programs.

The drop “came as a surprise to us,” said Jodi Grant, executive director of the Afterschool Alliance, in a panel presentation Tuesday unveiling the report “America After 3 PM: Demand Grows, Opportunity Shrinks.”

“Today there are 2.4 million more kids who don’t have after-school opportunities than in 2014. What’s even more troubling is that we know which kids have lost these opportunities,” Grant said.

The survey found that, while 10.2 million children attended after-school programs six years ago, only 7.8 million children were in after-school programs in early 2020.

It also found that a higher number of parents expressed a need for the programs.

This unmet demand “is greatest for families of color and low-income families,” Grant said. “They just can’t afford it anymore.”

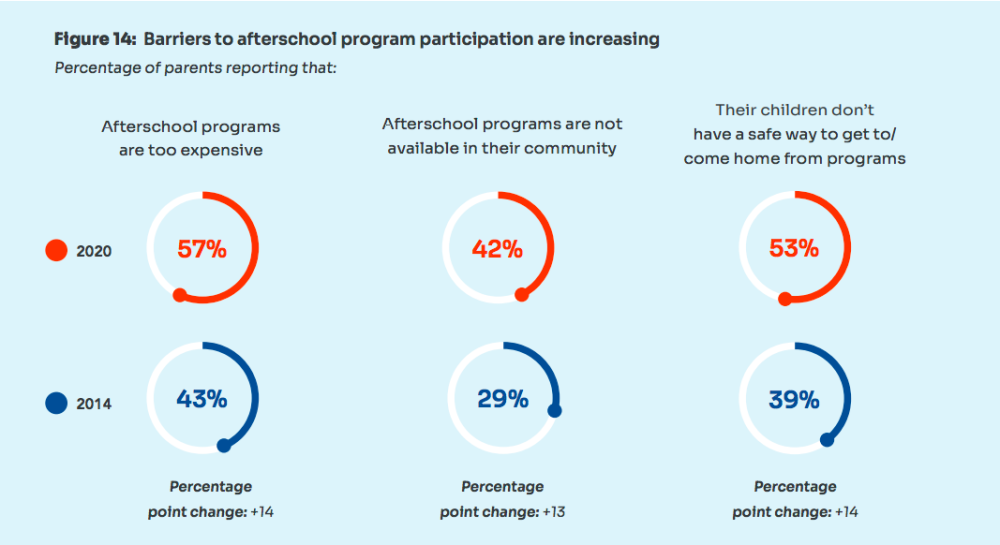

Parents reported that cost is an increasing barrier and that programs are not available. In 2014, 43% of parents said they couldn’t afford a program. Now, 57% of parents say it. More parents also said their children don’t have a safe way to get to a program.

The Afterschool Alliance has conducted its broad survey of households in 2014, 2009 and 2004.

One note of caution in interpreting the recent survey results: Parents reported a decrease in all forms of care outside of parent/guardian care, and a new company, Edge Research, was conducting the survey.

Afterschool Alliance

Chart from “America After 3 PM: Demand Grows, Opportunity Shrinks” report.

Nevertheless, the survey showed that the parents of 25 million children would like after-school programs if a program was affordable and available in their area.

The survey showed the opportunity gap for children based on income. Families in the highest income bracket reported spending more than five times as much on out-of-school activities annually than families in the lowest income bracket. The one-fifth with the highest incomes spent roughly $3,600 annually versus the one-fifth with the lowest incomes, who spent $700.

For example, 41% of high-income parents said they enroll their child in some after-school music, art or dance lessons. Only 21% of low-income parents said that.

After the pandemic

The survey preceded the COVID-19 outbreak in the United States. But an additional survey of 12,000 households in October (included in the report) showed a further drop in after-school participation. It found 11% of school-age children were in a program in October, compared with 14% at the beginning of 2020.

Even before the pandemic, after-school programs were an important support for low-income families, based on survey responses.

Zelda Waymer, president and CEO of the South Carolina Afterschool Alliance, called the programs a lifeline for parents. “They can’t get back to work without after-school programs,” she said at the report unveiling.

An open letter signed by 50 nonprofit and community-based organizations in August, ranging from the National League of Cities to the U.S. Chamber of Commerce Foundation, made a similar point.

The survey took a look at other supports.

In the January to March 2020 survey of households, low-income parents reported that the after-school snacks and meals were important to them. Two-thirds said programs connected them to community resources, such as dental clinics and financial planning assistance. Slightly more said that the programs connected them to parent education resources.

A parent from Fort Worth, Texas, also appeared on the panel. Stacy Medford said she worked from 9 a.m. to 6 p.m. but couldn’t afford to pay for after-school for her 6-year-old daughter. She moved to a different Fort Worth neighborhood strictly because the school, John T. White Elementary, offered a free after-school program.

Snapshot of programs

So who’s in after-school programs? The survey gives a snapshot.

Public schools provide half of all after-school programs across the country. In addition, community-based organizations often operate programs at school sites. That results in about three-fourths of after-school locations being on school property.

Aside from public schools, 14% of providers are Boys & Girls Clubs, 14% are private schools, 10% are cities or towns (often through their parks and recreation departments) and 10% are YMCAs.

Children and youth in after-school programs attend an average of 3.7 days a week for an average of 5.6 hours a week.

The average cost is about $99 a week; 15% of parents get assistance that pays for most of the cost.

The pandemic has changed the landscape, however. A separate survey of after-school providers in November by the Afterschool Alliance showed that just 68% are operating in person. Most of the others are offering some form of virtual programming. The ones that are open reported they are not able to accommodate as many students because of the need for social distancing and other virus protection protocols.

They also face increased expenses meeting the health and safety protocols, said Rico X, vice president of school age services at the YMCA of Middle Tennessee.

In recent years, after-school providers, assisted by supporting organizations such as state after-school networks, have focused on putting quality standards into place. This, plus a nationwide interest in STEM programming, may contribute to a higher positive feeling among parents of the value of after-school programs.

In the survey, a higher proportion of parents (94%) expressed satisfaction with their child’s after-school program in 2020 than in 2014 (89%).

Parents in 2020 were more likely to say that after-school programs support children’s social and emotional growth and help them succeed.

The report also showed how access to programs varies from state to state. For example, Georgia was one of the few states that saw a rise in the number of children in after-school programs.

Sen. Lisa Murkowski, R-Alaska, long a supporter of after-school funding, pointed out her state’s high participation in after-school programs in a video statement.