Design and Animation: Kelly Flynn/Sound Design: Sara Bernard/Reporting: Allegra Abramo

It’s nearing the end of another day of online school, and the fourth grader has pulled the headphones off his mop of light brown curls. His computer screen can’t compete with a nearby window on this sunny late-November afternoon. A camouflage gaiter rests beneath the boy’s chin as he chews on a straw.

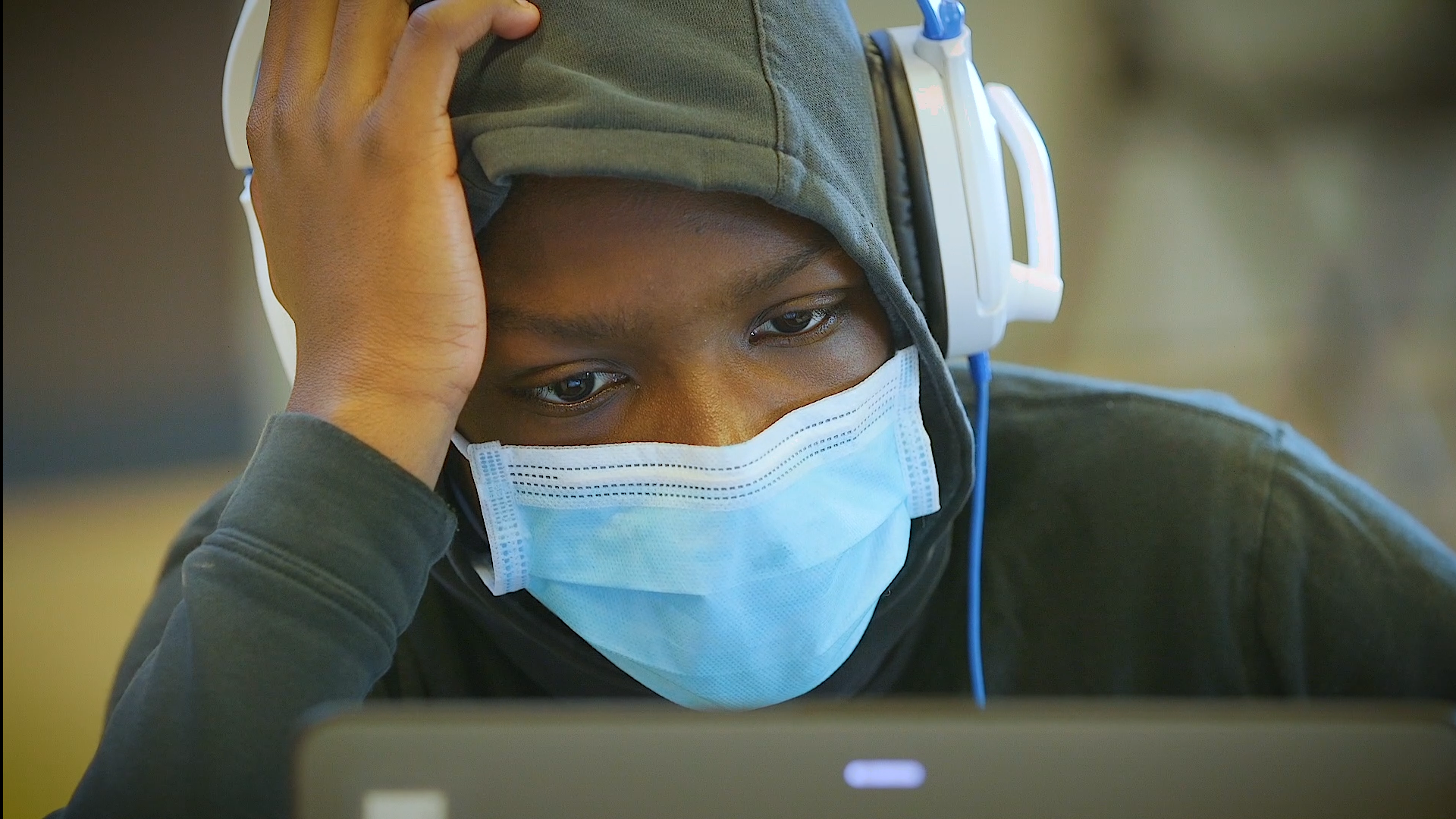

“Make sure your headphones are on and you’re listening, please,” says Daniel Russell, who is neither the boy’s teacher nor his dad. Russell, a youth services specialist at Metro Parks Tacoma, is in an entirely new role invented to solve an entirely new problem caused by the COVID-19 pandemic: When classes are run remotely, how do kids living in homeless shelters, cars or doubled up with relatives participate in online classes?

More than 40,000 K–12 public school students in Washington experienced homelessness in 2017–18, a number that has nearly doubled in the past decade and likely will continue to grow because of pandemic-driven job losses. For these youth, remote schooling might mean attending class in a shelter room they share with their mother and two siblings. It might mean missing classes due to glitchy Wi-Fi or insufficient cellphone data. And, especially for homeless youth who are on their own, it might mean not having an adult who can help them with assignments and prod them to stay on track.

That’s where people like Russell come in. Individual school districts, homeless shelters and community groups have cobbled together a patchwork of solutions. In Tacoma, the school district and parks department this fall set up what they call “camps” to serve children in kindergarten through ninth grade. The program buses a few dozen children, most living at nearby family shelters, to two community centers. There, they get a safe, quiet space to log on to classes, plus three meals, access to showers and plenty of play time. And, perhaps most important, adults like Russell make sure students are showing up for class and doing their work.

That extra support is crucial, because students experiencing homelessness, who are disproportionately students of color, already struggle to keep up in school. Four in 10 were chronically absent from school in 2018, according to an analysis of state data by Building Changes, a Seattle-based nonprofit focused on family and youth homelessness. Only 56% graduated from high school on time, compared with more than 83% of housed students. These disparities are likely to widen as a result of the prolonged school closures, advocates say.

The pandemic on top of the trauma of homelessness has been “a double whammy” for these youth, said Sara Berner, adolescent shelter program manager at YouthCare, which runs several emergency shelters and transitional living programs for youth and young adults in Seattle. “And I do worry that they’re going to continue to fall further and further behind,” she said.

Scrambling for solutions

When Gov. Jay Inslee announced in March that schools would cease in-person instruction to help stem the spread of the nascent coronavirus pandemic, YouthCare and other shelters that serve families and youth found themselves scrambling.

Suddenly, kids who normally would have been in school during the day were stuck inside shelters. Some students quickly received school-provided laptops or tablets, while others had to wait weeks or months. (At the end of October, more than seven months after schools shuttered, Inslee allocated $24 million in coronavirus relief funds to buy 64,000 devices for students still lacking them.) Shelters’ internet connections couldn’t support the number of students logging on to classes, shelter managers say. Common spaces had to be converted into classrooms.

“It’s a fundamentally different service model, where we are now essentially a boarding school,” said Shoshana Wineburg, director of public policy and communications at YouthCare, “except it’s also a boarding school in which everything is in one main room.”

And not just one boarding school. Since homeless students have the right under federal law to continue attending their home school district even if they move outside it, a dozen children in a shelter can be attending a dozen different schools.

“We’re now running seven to eight virtual high schools within one program, and all have their own curriculums and own way that they’re doing online learning,” Wineburg said. “Youth counselors are suddenly having to troubleshoot all of these technological things,” and some are tutoring in subjects they’re unfamiliar with.

Casey Madison/Tacoma Public Schools

Julian McGilvery, a youth services supervisor with Metro Parks Tacoma and former juvenile parole officer, takes children’s temperatures as they enter the STAR Center for a day of remote schooling. Each student has a health and temperature check before entering.

At Tacoma’s camps, the counselors are not schoolteachers, but they help students with academics when they can. In a room with a half-dozen second and third graders, a counselor sat next to a boy attending the program for the first time. As they read through a math problem together, a child at a nearby desk wriggled out of his chair and onto the floor. “Do you think that’s addition or subtraction?” the counselor probed, before asking the other child to sit in his chair. “Read it one more time.”

When students fall behind, teachers alert the counselors, who then nudge their charges. “A lot of these kids, if they weren’t here, they wouldn’t be completing their assignments,” said Julian McGilvery, a youth services supervisor at Tacoma Metro Parks who oversees the camp serving middle schoolers.

Online learning presents extra barriers for students who have learning or behavioral challenges that qualify them for special education, or who are learning English. Both those groups are overrepresented among students experiencing homelessness.

For students learning English (who make up 17% of those experiencing homelessness compared with 12% of housed students, according to Building Changes), classes can be particularly hard to follow and participate in over a computer. They also lose important opportunities to practice and improve their English.

“It’s different when talking to people in person, you learn so many things,” said a high school senior who came to the U.S. from Guatemala as an unaccompanied minor at age 16. Today he’s doing his classes from his room in a transitional living program run by Friends of Youth, which operates shelters for homeless youth in King County. “I would be learning much English going to school,” he said.

The one in five homeless students who have a special education plan also are struggling, their caregivers say. Most have lost access to paraeducators who assist students with special needs, although some schools offer limited in-person instruction for special education students.

Dorothy Edwards/Crosscut

Gosefa Velázquez (left) and her three children had been staying at the shelter Mary’s Place in Seattle when the pandemic started. Her daughter Janice, a sixth grader, is on her lap. Velazquez is also attending classes online, studying business administration. “I do my homework and then help them with their homework,” she said. “It is really hard right now for them going to school because they are locked down all the time.”

Gosefa Velázquez, who lives with her three children in a Seattle family shelter run by Mary’s Place, worries that her 11-year-old son, who normally receives one-on-one support and had to repeat fifth grade, might be held back again. “It’s really hard for him to focus on the classes,” Velázquez said in an interview at the shelter in mid-November. “It’s stressful, because he’s not listening, he’s not doing what he has to do.”

Velázquez’s daughter, 11-year-old Janice, used to be an honors student, she and her mother said. Now she’s at risk of failing classes because she hasn’t completed several assignments. On a computer, Janice said, “you can go to games, you can go to YouTube — other things distract you sometimes.”

So that Velázquez can work part time and attend her own online college classes, her three children spend school days at the Boys and Girls Club, in a program similar to Tacoma’s that also is available to the general public. But that has come with other tradeoffs.

In early December, the family was quarantining in a hotel for a third time. Two of those resulted from potential COVID exposures at the Boys and Girls Club, Velázquez said (no one in the family has become ill). Trying to do school while cooped up with four people was hard, especially when the Wi-Fi kept going out, Janice said. Her exhausted mother joked, “I want to make a tunnel and escape.”

No COVID outbreaks have occurred at the Tacoma camps, according to the program manager. Signs posted around the community centers remind youth to “Keep one zebra of space between you and others.” Now Russell, the youth services specialist, just says “Zebra!” when they get too close to each other. “If we had a dollar for every time we said zebra,” he said, “we could retire.”

Students falling through the cracks

A year ago, the Tacoma public school district had 1,228 students who qualified as homeless under the federal definition of lacking “a fixed, regular and adequate nighttime residence.” This school year, it says it has identified only 761 so far.

That’s not because fewer are experiencing homelessness. Rather, school counselors and social workers can’t find them.

Instead of the usual paper questionnaire that goes home in kids’ backpacks, school counselors are visiting shelters to find kids and meet regularly with parents. At Tacoma’s DeLong Elementary School, most of the 43 students identified so far live in a nearby family shelter, said Courtney Lawson, the school counselor and lead for homeless students services. But she knows that leaves out many more families who have had to move in with relatives because a parent lost a job. Statewide, nearly three-quarters of students defined as homeless were doubled up due to economic hardship.

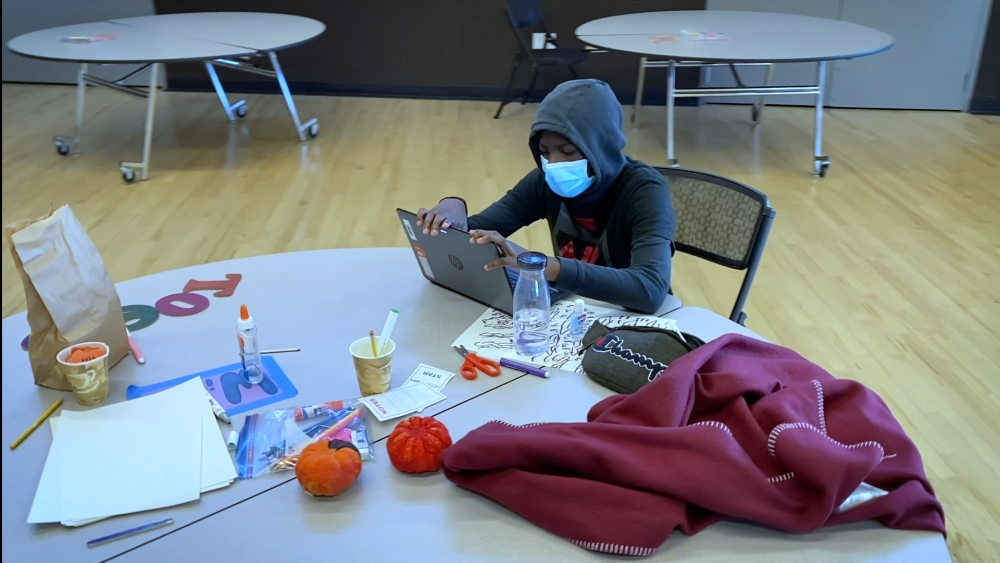

CASEY MADISON/TACOMA PUBLIC SCHOOLS

Each student gets their own assigned table and supplies provided by the school district. Schools also provide breakfast and lunch, and the children take home food for dinner.

Without that connection, families are missing out on the many ways schools provide help, from food and clothing to assistance signing up for insurance and finding housing.

“I’m worried we’re missing families,” Lawson said. “And that scares me, that haunts my dreams.”

Most of the 50 children regularly attending Tacoma’s camps also reside in the area’s two family shelters. The program could expand to a total of four sites with the capacity to serve about 100 children, still just a fraction of all those experiencing homelessness in the district.

Some parents prefer not to risk COVID exposure by sending their children to learn in a group setting, Lawson said, so many youth still attend school from shelters. Children there can have a hard time finding a quiet corner in which to study.

“I had a kiddo learning on her bunk bed with her mom,” said Lawson. “And her teacher, not realizing that she was at the shelter, was like, ‘If you don’t sit next to your mom, maybe you would be able to focus better.’ And she had nowhere else to go.”

A widening gap

Students experiencing homelessness are missing out on more than academics when they can’t go to school. “They’re missing out on the connections that they have with people … that have been constantly there for them,” said YouthCare’s Berner. That could be a trusted school counselor or teacher, she said, along with friends and perhaps even siblings or cousins who attended the same school.

For many youth, these connections are their motivation to attend school, she said, and now that’s been taken away. She and other youth shelter workers say it’s becoming harder and harder for kids to stay engaged in school.

CASEY MADISON/TACOMA PUBLIC SCHOOLS

Metro Parks McKinney Vento Camps provide vital access to technology for middle school students experiencing homelessness.

Standardized testing data from this fall suggest smaller learning losses as a result of the spring school closures than some studies had predicted. Three different national tests found students lost ground in math over the spring and summer, but performed nearly as well in reading. But, with many schools remaining largely or entirely virtual, learning losses are likely to grow. A recent analysis by McKinsey & Company estimates that, by the end of the school year, Black and Latino students could be 11 to 12 months behind in math, compared to seven to eight months for white students, unless schools make significant improvements in remote teaching or return to in-person instruction in January.

Addressing these growing inequities will require more robust funding, advocates said. The state’s 295 school districts receive $2.5 million a year in state and federal grants to support homeless students, but need closer to $29 million, according to a 2019 report by the Washington state auditor. Much of that funding helps pay the salaries of homeless student liaisons that schools are required to have under federal law. Yet two-thirds of liaisons spend four hours or fewer a week supporting homeless students, according to the Office of Superintendent of Public Instruction.

One lesson reinforced by the pandemic, said school counselor Lawson, is the importance of relationships with families. But building those relationships takes time that school staff often lack. Lawson said she’s fortunate to work in one of the few schools in her district that has both a social worker and a counselor, and “that extra person has been critical for getting needs met.”

Lawson sees the difference it has made for one of her homeless students. When the family was doubled up with relatives in another school district, the child struggled just to show up, she said. But since his family moved to a shelter in Tacoma, Lawson and the social worker have met with them regularly, masked and distanced.

“This kiddo has been in class every day,” she said. “At one point, he’s in the lobby in the shelter, and there’s kids running around everywhere, and it’s loud. But he’s there, and his mom is sitting there watching him, making sure that he’s signed on.”

Related videos, stories and podcasts

- Video and story: Washington state young adults often end up homeless after leaving treatment

- Podcast and story: Upended by COVID-19, some nonprofits went online, on the road and otherwise innovated to aid homeless youth

- Podcast and story: Youth leaving foster care, juvenile and other systems are aim of Washington housing effort

- Podcast and story: Washington’s new youth homelessness ‘Lifeline’ service lags

***

Allegra Abramo is a freelance writer whose stories and photos have appeared in ProPublica, NBCNews.com, InvestigateWest, and other local and national outlets. She grew up on the East Coast but loves the mountains and trees of the Pacific Northwest too much to ever go back.

This story has been updated.

This article and animation, done in collaboration with Crosscut, is part of a series by Youth Today on homelessness in Washington state. Read the first installment and watch the video here. This project is made possible in part by support from the Raikes Foundation. Crosscut and Youth Today maintain editorial control.