IVANOVA TANJA/SHUTTERSTOCK

IVANOVA TANJA/SHUTTERSTOCK

When Han Johnson thinks about her younger self, she wonders how she would have survived the COVID-19 pandemic during high school. It’s hard enough for her now as a college student without a home and family.

After the virus hit in March, her college closed, and Johnson, a sophomore studying archaeology and environmental science, had three days to move out of the dorm at Weber State University in Ogden, Utah. She had nowhere to go. She’d been on her own for three years.

“It’s a constant thing, every summer and every holiday,” trying to find somewhere to live until school resumes and the dorm opens, she said in a July 14 online congressional briefing sponsored by four nonprofits that advocate for homeless and foster youth. One of them was SchoolHouse Connection, which partners with educational and other institutions to help homeless youth gain access to a good education.

“It’s a constant thing, every summer and every holiday,” trying to find somewhere to live until school resumes and the dorm opens, she said in a July 14 online congressional briefing sponsored by four nonprofits that advocate for homeless and foster youth. One of them was SchoolHouse Connection, which partners with educational and other institutions to help homeless youth gain access to a good education.

Johnson left home as a teenager after years spent with a mentally ill single mother who would threaten her with a knife, she said. When she was in seventh grade, she first reported her situation to authorities. Because she was a A student, a social worker didn’t believe she could be in abusive circumstances, she said.

She ran away to a youth shelter and lived there a year while finishing high school.

Johnson and three other college students spoke at the congressional briefing, which was held to urge Congress to provide funding for homeless youth and families during the pandemic.

One goal was to push for passage of the Emergency Family Stabilization Act, a bipartisan-sponsored bill that would provide emergency funding to community organizations to address the needs of homeless youth during the pandemic. SchoolHouse Connection is urging Congress to include it in the next COVID funding bill.

Johnson also urged youth workers and teachers to make a concerted effort to reach out to young people right now.

“Reach out to them in more than one way,” she said. “A lot of children have slipped through the cracks.” Ask what they need, she urged.

“It’s really about asking and listening,” she said.

In addition to SchoolHouse Connection, the event was sponsored by National Network for Youth, Family Promise and First Focus on Children. The organizations also urge the authorization of $300 million in funding for the Runaway and Homeless Youth Act, which provides for street outreach, crisis intervention and transitional housing. Reps. John Yarmuth, D-Ky., and Don Bacon, R-Neb., who sponsored the legislation, also took part in the briefing.

Impact of pandemic on homeless kids

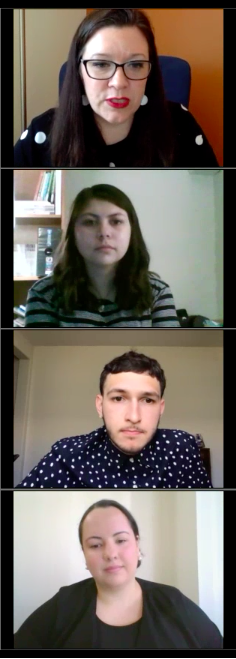

From top to bottom, Darla Bardine, executive director of National Network for Youth; students Yesenia Garcia and Anthony O’Leary; and Jordyn Roark, SchoolHouse Connection director of leadership and scholarships.

Johnson and the other students explained the difficulties they faced and how the pandemic would have made things far worse.

“If my education had moved online [while in the youth shelter], we would have had a battle for computers and constant chaos,” Johnson said. The shelter had 14 residents and six computers, she said.

“If I’d been stuck at home during quarantine with my mom, I don’t know if I would have survived. School was always my safe space,” she said.

Another student, Yesenia Garcia, 18, has a scholarship to attend Heritage University in Toppenish, Washington, this fall. She works as Swan Vocational Enterprises, a vocational training program for Native American youth in Yakima, Washington. Growing up, she lived with her five siblings in two tents at a campsite after her parents lost their house. Her parents were drug users and her stepfather was abusive, she said.

The family had an electric generator they used for one hour a day at the campsite. Had the pandemic occurred then, Garcia wonders how she would have done schoolwork online in those circumstances.

“I would have been trapped in that camp,” she said. She currently lives with her boss, who offered her a place to live after her mother died in April.

Christine (who wanted her last name withheld for privacy reasons), 19, is a rising junior studying communications at Stanford University in New York. She said her family had moved 18 times when she was growing up. Her mother was a nurse, but economic stability was elusive. They lived in various hotels and once spent five days living in their rented storage facility, Delianne said. She and her sisters would leave the storage unit at 6 a.m. when her mother went to work and spend hours during the day in the public library, she said. She described living in hotels where a sex worker was murdered in the next room, a police standoff occurred across the hall and pimps tried to recruit her and her sisters.

School was the place she received assistance. The assistant principal kept an eye on her and her sisters, let them spend time in her office and brought them meals, Christine said.

Because she lived in a hotel and was not technically homeless, she said she did not qualify for resources through programs for homeless families and youth. Programs often define homelessness in a narrow way that limits help for young people who need it, she said.

Anthony O’Leary, 19, has completed his freshman year at UCLA, where he’s interested in pursuing sports management. He, too, had to scramble to find a place to live when his housing contract at the university ended.

A gap in policy?

When O’Leary was younger he was placed in foster care as a result of his father’s abuse, he said. Other relatives took guardianship, allowing him to leave the foster care system. He eventually returned to live with his father, whose custodian job was not enough to make ends meet, O’Leary said. The family was evicted and moved from hotel to hotel, he said.

Had the pandemic occurred then, O’Leary said he would not have had access to the technology to do schooling online.

Living in a house where physical abuse was common would have created even more anxiety, he said.

“School was a second home,” he said.

O’Leary urged teachers and school staff to use the connections they’ve built with students.

“Have open arms, especially for those homeless youth who don’t necessarily have a place to go,” he said.

O’Leary was able to get support through programs including Guardian Scholars, which assists California foster youth in getting a college education. Many of the supports he received would not have been available had he not been in the foster care system, he said.

The Emergency Family Stabilization Act uses a broad definition of homelessness and recognizes the forms it takes for young people, said Barbara Duffield, SchoolHouse Connection executive director. Narrow definitions have been a barrier to accessing services, she said. The bill would fund existing systems that already work with homeless youth, she said.

“It’s able to meet a wide range of emergency needs” and fills a gap left in previous COVID-19 relief bills, she said.

“There’s a significant gap in policy as it relates to homelessness,” she said. SchoolHouse Connection is asking for $2 billion to be allocated in the act.

It also would like to see $500 million be dedicated for the existing McKinney-Vento Act, which identifies homeless youth in the public school system and provides services for them.

“School is often the only source of support and services for children and youth experiencing homelessness,” Duffield said.

This story has been updated.