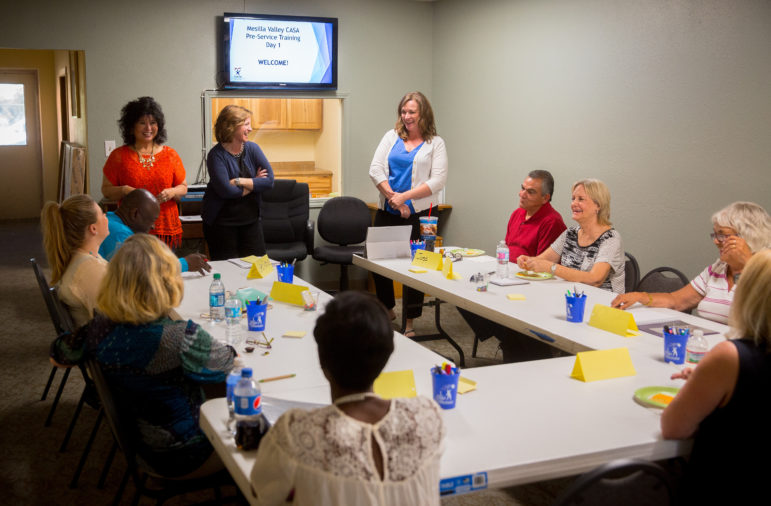

Jett Loe/Sun-News file photo

Mesilla Valley CASA staff and volunteers gather at the CASA offices for the beginning of 30 hours of training. Doreen Gallegos is at the head of the table in a red shirt. Brandie White is in a white cardigan at the head of the table on April 24, 2016.

In April, as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic, the state Children, Youth and Families Department (CYFD) extended its foster care services to youth who have turned or will become 18 years old between February and July 2020. Instead of exiting from care and into an uncertain, coronavirus-impacted world, these older foster youth will continue receiving crucial state services such as monthly stipends and health insurance.

But what if a youth happened to turn 18 on Jan. 30, for example, or at the tail end of 2019? They were out of luck.

Mesilla Valley CASA recognized that youth who didn’t meet the Feb. 1 cutoff might fall into dire straits.

“CYFD has really been onboard to try to help us because they’re under such restrictions and they have their hands tied in certain areas,” said Doreen Gallegos, Mesilla Valley CASA executive director. “We’re not under that government reach and as a nonprofit, we can maneuver a little easier sometimes.”

CYFD has been under strict guidelines imposed by the New Mexico Supreme Court, which continues to largely outlaw in-person visits between children in state custody and their biological parents or guardians in abuse and neglect cases.

In Las Cruces, Mesilla Valley Court Appointed Special Advocates is making sure that these youth aren’t falling off the cliff. CASA, a national organization that has been scrutinized by the public and in several legal challenges, has been able to fill some of the gaps. The private nonprofit hasn’t been subjected to a number of the state government’s public health restrictions that have hamstrung CYFD, the state’s child protective services organization.

Local CASA volunteers, who advocate for foster youth in Las Cruces’ Third Judicial District Children’s Court proceedings, normally work with youth ages 12 to 17. However, Mesilla Valley CASA, realizing that older youth could be left behind, have delivered food boxes, housing services and other supports to this susceptible population.

“We’ve really had to scramble, but we’re trying to make sure kids don’t fall through the cracks,” Gallegos said. She has also been a Democratic state representative in Doña Ana County since 2013. “The good piece is that if COVID[-19] wouldn’t have hit, we probably wouldn’t have gotten involved because we’ve always been strict with age 18,” she said.

‘Somebody still has to be there’

In March, shortly after coronavirus shut down schools, two youth who CASA works with were forced into a long-stay hotel. According to Mesilla Valley CASA program director Brandie White, the local housing authority had halted services for a few weeks, leaving the youth with nowhere else to go.

A CASA volunteer contacted a friend who owns a small apartment building, who agreed to let the kids move into the complex and helped them complete housing voucher paperwork. CASA volunteers called the electric company to establish service, and bought towels, shower curtains and cooking items for the young people.

“We had to work really hard and creatively to find housing services for youth,” White said. “We’ve collected the things that we could collect so that they don’t have to buy them. I actually have a box of pans in my office that have been donated to a youth.

[Related: NM Schools Providing Academic Coaches, School Packets, Food to Struggling Students]

[Related: Gallup Schools Hope For CARES Funding for Tech Purchases]

[Related: State Outreach Helping Aged-out Foster Youth Amid Anxiety About Lost Oil Field Jobs]

[Related: Pandemic Accelerated Rollout of Extended Foster Care ‘in Really Good Way’]

“Somebody still has to be there for some of these youth who don’t have reliable adults in their lives,” she said. “CASA volunteers have filled in some of those gaps” such as helping young people open bank accounts and procuring Social Security benefits by phone since the Social Security office is closed for in-person appointments.

Gallegos and White say that other area organizations, such as local food pantry CASA de Peregrinos (House of Pilgrims), which is led by Lorenzo Alba, contributed vital assistance to the two youth who were forced into a hotel due to the pandemic before they moved into an apartment.

“He knew that the youth didn’t have access to a stove and that they only had a small refrigerator, so he made specific food boxes for their needs,” White said.

COVID adjustments

“Our CASA volunteers have been the ones to move furniture into a youth’s apartment at this time because there are so many restrictions on CYFD from the state about what kind of work they can do in the community,” White added.

The pandemic has also forced Mesilla Valley CASA to adjust its volunteer training curriculum. Traditionally, new volunteers enroll in a 30-hour classroom-style course followed by in-person court observation. Now, everything is done by videoconferencing.

Court hearings also look drastically different. White says the judge, court reporter and the attorney for CYFD are the only ones allowed in the courtroom. Everyone else appears by phone.

“We’re handing in reports differently and making sure that the judge still has the information that she needs to make long-term decisions for these kids,” White said. “It has been an ongoing adjustment.”

Gallegos admits that each day brings a new test for Mesilla Valley CASA but also a chance at improving the system for kids.

“It has definitely been challenging but I’m really proud of my staff because kids right now are in more danger than ever. They’re not going to school and there’s not a lot of outside contact. People are home and frustrated and scared … and it leaves kids much more vulnerable,” she said.

“We’ve always known that it’s a problematic system, but now we’re really walking through the process with these kiddos and we’re committed to try to make it better,” she said.

This story is part of a Youth Today project on foster care in New Mexico. It’s made possible in part by the May and Stanley Smith Charitable Trust. Youth Today is solely responsible for the content and maintains editorial independence.