Family Independence Agency

Photo is from a June 2000 publication from the state of Michigan.

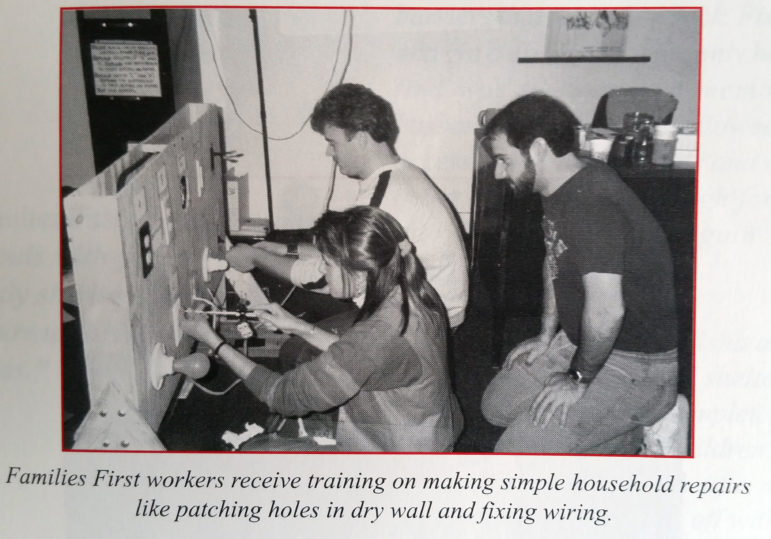

The first time I saw the photo, nearly 20 years ago, I was so moved it almost made me cry. That may seem an odd reaction to a picture of a bunch of people learning basic home repairs. But the people learning to patch holes in drywall and fix wiring were therapists. Their master’s degrees were in social work or related fields.

Richard Wexler

They were learning these skills because, for the therapy they were about to practice, they’re essential. They were caseworkers for Michigan’s Families First program, an Intensive Family Preservation Services program that rigorously follows the model of the first such program, Homebuilders, in Washington state. The picture is in an old publication commemorating the program’s 10th anniversary. That one photo explains why such programs are so effective — and also why they have been the object of a decadeslong smear campaign by pillars of the child welfare establishment.

Homebuilders was created in 1974. The very term “family preservation” was invented to describe Homebuilders. The program has been tested, studied and proven effective over and over again. But research has never been a match for politics in child welfare.

Perhaps now, things will change. Because now has come the ultimate measure of vindication. Homebuilders is one of the very few programs that has met the absurdly high standards for approval by a clearinghouse established as part of the Family First Prevention Services Act. In fact, it received the highest rating from the clearinghouse. That simple fact means the Family First law now has the potential to be vastly more useful than skeptics such as myself thought it would be.

WHAT IT IS AND WHAT IT ISN’T

Homebuilders is not for every family. There are plenty of cases in which foster care could be avoided simply by providing basic, concrete help — child care, housing or cash. Homebuilders is for tougher cases; a crisis intervention program for situations in which the child is on the verge of losing her or his family by being taken to foster care because of a real safety threat that cash alone can’t fix.

A Homebuilders intervention is short but extremely intense. Family preservation has been falsely characterized as a “quick fix.” In fact, Homebuilders workers have caseloads of no more than three, so though they are with a family for no more than six weeks, they can spend several hours at a time with that family — often equivalent to a year of conventional “counseling.”

The end of the intervention does not mean the end of support for the family. The Homebuilders model requires that the family be linked to less intensive support after the intervention to maintain the gains made by the family.

The worker spends her or his time in the family’s home, so s/he can see the family in action and so the family doesn’t have the added burden of going to the worker’s office. The worker gives his or her home phone number to the family and is on call 24/7.

The worker begins with the problems the family identifies, rather than patronizing the family and dismissing their concerns.

Workers are trained in several different approaches to helping families, so they don’t become hostile to those families if their first attempts to help don’t work.

None of that explains why Homebuilders generated such hostility. But this does: Family preservation workers combine traditional counseling and parent education with a strong emphasis on providing “hard” services to ameliorate the worst aspects of poverty.

For traditional social workers that strikes at the heart of their self-image as noble healers — and it involves a lot of scut work. It was explained best by Malcolm Bush in a quote I’ve cited before from his book “Families in Distress”:

“The recognition that the troubled family inhabits a context that is relevant to its problems suggests the possibility that the solution involves some humble tasks … This possibility is at odds with professional status. Professional status is not necessary for humble tasks … Changing the psyche was a grand task, and while the elaboration of theories past their practical benefit would not help families in trouble, it would allow social workers to hold up their heads in the professional meeting or the academic seminar.”

At its worst, this desperate desire to see themselves as reserved solely for “grand tasks” can be seen when a caseworker simultaneously brags about her master’s degree and complains about having to drive foster children to appointments, or even wait with them in the E.R. — instead of seeing both as a perfect opportunity to learn about the children and discover new and better ways to help them and their families.

But Homebuilders makes things even worse for traditional caseworkers. When you simply point out that, say, what the family needs is help to clean and repair the house, the traditional caseworker can say, “Well, yes, and isn’t that too bad. But we don’t do windows, so we’ll have to take away the kids.” One study found that workers actually are, to use that favorite child welfare phrase, “in denial” about housing problems because they can’t — or don’t want to — fix them.

Homebuilders doesn’t allow such copouts. Homebuilders demands what is seen in that photo: The therapist — complete with master’s degree — is expected to actually help with the windows, and the floors, and the repairs. By actually helping with such things, the Homebuilders worker can forge a bond with a family that is beyond the reach of the typical patronizing approach. Consider this example from Lisbeth Schorr’s book, “Common Purpose.”

“A [Homebuilders] therapist told of appearing at the front door of a family in crisis, to be greeted by a mother’s declaration that the one thing she didn’t need was one more social worker telling her what to do. What she needed, she said, was to get her house cleaned up.

“The Homebuilders therapist … responded by asking the mother if she wanted to start with the kitchen. …

Homebuilders also plays a vital role in the first weeks after a family is reunified — when bonds are most fragile and stress is highest. Consider this recent case involving three sisters reunified because Los Angeles County officials felt elderly family members living with their foster parents were at risk of contracting COVID-19:

“For the three sisters, that solution may have sounded better than facts on the ground would allow. They said soon after moving back in with their parents on March 25, things went downhill. Family disagreements — exacerbated by household stress after both parents lost their jobs — had made staying together too hard, and ‘unhealthy habits’ returned, Natasha said.”

Homebuilders is designed to change the facts on the ground. What if, instead of simply removing the children again, Los Angeles County had sent in a Homebuilders worker? And yes, even now that can be done. Butler County, Ohio, for example, understands that few jobs are more essential than keeping families together. The county child welfare agency and its contractor are continuing their Intensive Family Preservation Services program, which appears to follow the Homebuilders model.

The intensity of a Homebuilders intervention gives it another advantage: A Homebuilders worker is likely to be the first to know when a family really can’t be preserved, and the children must be removed. That helps account for the program’s outstanding track record for safety — something foster care can’t claim.

THE SMEAR CAMPAIGN

Homebuilders is one of the most intensively studied interventions in child welfare. Study after study found that when programs stick rigorously to the Homebuilders model they are highly effective and they are safe.

But those threatened by the whole Homebuilders approach mounted a successful two-front smear campaign. First they cited the interim results from one study of programs, most of which didn’t follow the Homebuilders model. Instead they diluted the model with higher caseloads and less intensive help.

Not surprisingly the interim report found that in most locations studied, the program didn’t work. Professor Ray Kirk of the University of North Carolina aptly called this “a non-finding from a failed study.” (Even this study, in its final version, found enough benefits in enough places to be cited by the Family First clearinghouse as evidence of Homebuilders’ effectiveness.)

Second, though Homebuilders is a trademark, “family preservation” is not. So whenever a child “known to the system” died, anything labeled “family preservation” became the scapegoat.

In perhaps the most notorious example, in 1993, 3-year-old Joseph Wallace died after being in a family preservation program that diluted the Homebuilders model. But even then, the family preservation worker was the one — the only one — to sound the alarm that Joseph was in danger and recommend against reunification. Yet still family preservation was blamed — setting off one of the largest foster care panics in modern child welfare history.

It’s amazing the lengths to which some social workers will go to avoid having to scrub floors or repair wiring.

WILL PERCEPTION CATCH UP WITH RESEARCH?

The research about Homebuilders’ effectiveness has been piling up in the years since that one failed study.

A detailed review of studies conducted by the Washington State Institute for Public Policy found that:

“IFPS programs that adhere closely to the Homebuilders model significantly reduce out-of-home placements and subsequent abuse and neglect. We estimate that such programs produce $2.59 of benefits for each dollar of cost. Non-Homebuilders programs produce no significant effect on either outcome.”

Then the California Evidence-Based Clearinghouse for Child Welfare — the model for the one created by Congress in the Family First Act, gave Homebuilders its second highest rating — something achieved by only about 16% of the programs it reviews.

And now the Family First clearinghouse itself has found that Homebuilders is one of only 14 programs to meet the extremely high bar that any program has to meet to receive the most access to Family First funds.

All that’s needed now are child welfare leaders with the courage to use a large part of the money made available through Family First on Homebuilders. Unfortunately, such leaders may be even harder to find than social workers willing to learn how to repair wiring.

Richard Wexler is executive director of the National Coalition for Child Protection Reform.