Festa/Shutterstock

.

Violence is the only major health epidemic not currently managed by health and public health methods. As a result, many areas throughout the world continue to experience unmanaged violence epidemics, including local epidemics of community violence, domestic violence, hate crimes, mass shootings, belief-inspired violence, violent recruitment and terrorism, group-on-group violence, violence between states and violence against oneself, or suicide.

Gary Slutkin

Although the problem of violence appears stuck, and even at times and in some places worsening, there is now a clear way out. All these types of violence have been shown to be contagious. Therefore, the same methods we use to manage other epidemics can be used to prevent violence, manage outbreaks and potentially make acts of violence rare — just as cases of other contagious problems, such as plague, leprosy, SARS and bird flu, have become rare.

This approach involves treating violence as a contagious health issue, using the same methods we have used to contain these other diseases. A transition to this approach to violence requires that we re-understand the people affected as having a transmissible health problem, and put in place epidemic control systems with specific workers to interrupt the spread, change the behaviors and influencers of behavior of those most likely to spread violence, and change the norms locally and more broadly that encourage the spread.

Re-understanding people showing signs of violence

Violence is a contagious problem. This is not just a metaphor. Recent advances in neuroscience, behavioral science and epidemiology demonstrate that violence behaves like other contagious problems, a discovery that requires us to understand people who behave with violence in a new light. Violence has been shown to be transmissible in virtually all forms and transmissible between syndromes. People who have been exposed to and infected with violence need and deserve care, support and treatment to heal, perhaps when even in an asymptomatic or incubating form of the disease.

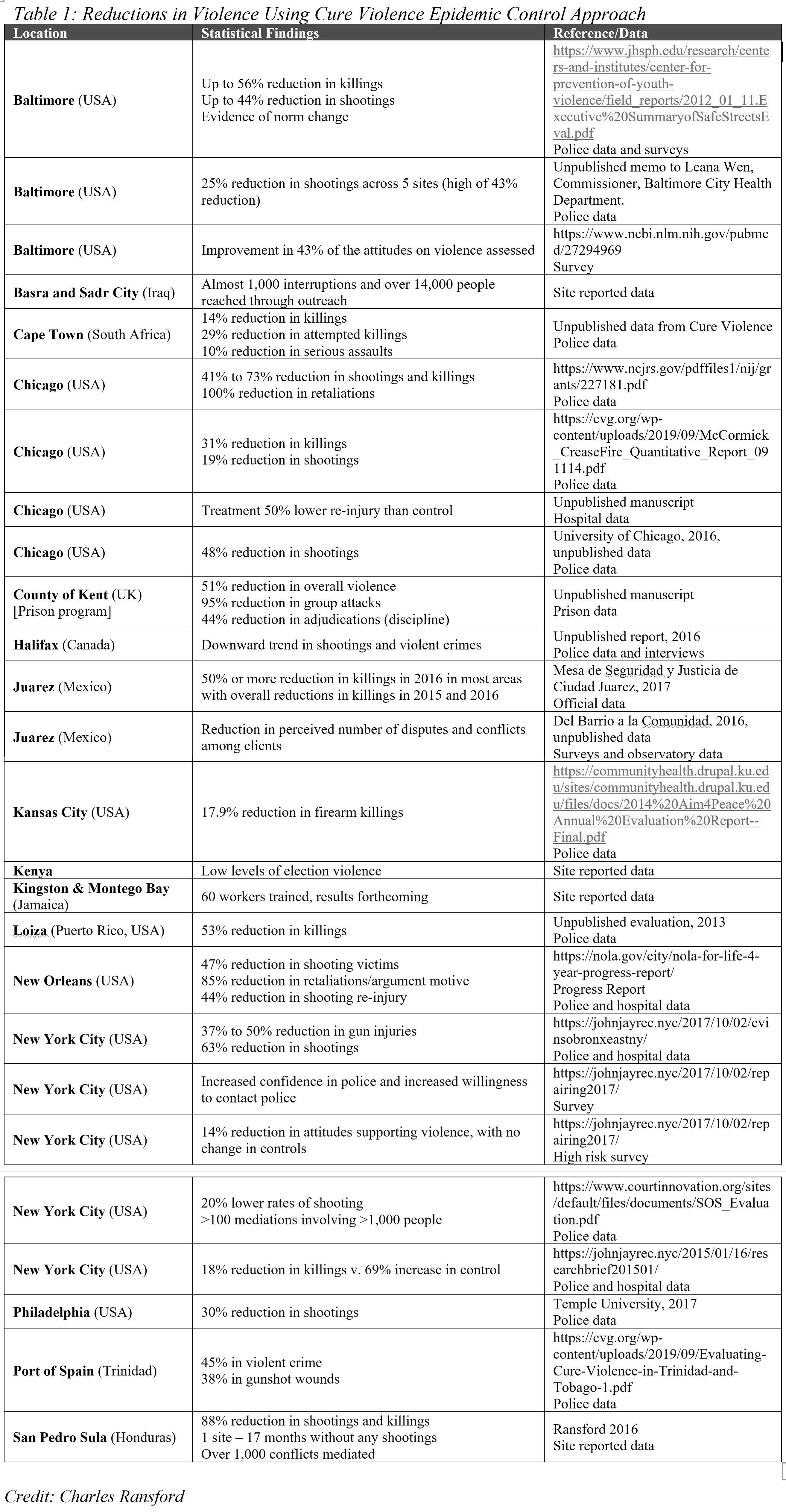

Charlie Ransford

People who have acquired “violence disease,” as evidenced by clear signs and symptoms, as well as those at risk of progression to a symptomatic form, have acquired the initial infection in the same general way that people acquire tuberculosis or cholera — through exposure. The contagion of violence, initiated by exposure to traumatic events, is then processed by the brain into scripts, copied behaviors, local norms and social expectations.

In other words, the brain mediates exposure to violence, as the lungs serve as the organ where replication of tuberculosis occurs and as the intestines serve as the site where more cholera is produced. The result is that more of the contagion to which an individual is exposed is produced — tuberculosis and cholera organisms multiplied and potentially transmitted to others, violence scripts and expectations replicated and transmitted to others. As for most contagious processes, not all persons exposed develop a clinical problem, due to modulating factors, in particular dose, social proximity and age at time of exposure.

Research shows that exposure to violence that can result in transmission includes both victimization and direct observation. New contagious variations are occurring through social media.

Some of the brain processing mechanisms are now known or hypothesized, including cortical mirror neuron-like networks for copying behaviors, dopamine and pain centers mediating social factors (e.g. need for attention and approval), and limbic systems that can enhances contagion through hostile attribution (the tendency to interpret others’ behaviors as having hostile intent) and hyper-reactivity.

Different parts of these processes are thought to be responsible for contagions of child abuse, family/spousal violence, retaliations in gang or cartel violence and warfare, mass shootings and terrorism. These phenomena have been well summarized by the Institute of Medicine and demonstrated by recent studies. They can also be seen in everyday events, such as when social pressure encourages violent responses.

However, as has now been shown in multiple geographic settings and contexts, these brain mechanisms can be countered, bypassed or prevented by the application of well-designed, highly granular, peer-based outreach methods of persuasion, social learning and local norms.

The epidemic approach for managing contagious violence

Understanding violence as contagious allows us to understand communities that experience violence as having epidemic outbreaks. Within each of these local epidemics, the persons or groups who are spreading the contagion, and the hot spots where violence is most likely to spread, are well known to community and local leaders. Yet, unlike other epidemics, health workers are not deployed to respond.

Over the last 20 years, Cure Violence and its partner organizations and agencies have used epidemic control methods to prevent and reduce community violence in more than 60 communities in more than 20 cities in the U.S. and on five continents around the world. Some of the reported and evaluated results of these methods are summarized in Table 1.

The basic approach to reducing epidemic violence will be recognizable to those who have worked in epidemic control. Specialized community-based health workers are selected, trained, supervised and supported. They work closely with the health sector to reduce spread and reverse epidemic processes. The Cure Violence approach accomplishes this aim through three components:

- Detect and interrupt the transmission of violence by detecting situations in the community where the risk of future violence is high and preventing these situations from becoming lethal, thus interrupting the contagion where it is potentially occurring.

- Change the behavior of the highest potential transmitters by identifying those at highest risk for violence and working to change their behavior (in the same way that health outreach workers identify and treat those suspected of having tuberculosis, syphilis, gonorrhea, HIV/AIDS or even Ebola).

- Change community norms through public education campaigns, community events, community responses to every shooting and community mobilization.

For community violence, a new cadre of health workers is selected from among the groups where the violence is occurring. The most important characteristic of these workers is credibility, which gives them the ability to gain the trust of those at highest risk for engaging in violence. Some of these new workers include:

- Violence interrupters prevent violence by identifying and mediating potentially lethal conflicts in the community and following up so that the conflict does not reignite.

- Outreach workers focus intensively on behavior change with a small caseload of the highest-risk individuals, including daily interactions, home visits, street check-ins, referrals to services and mentorship.

- Site supervisors coordinate with neighborhood associations, service/resource and other providers to change norms and facilitate access to health, education, employment, housing and other support services.

- Hospital responders prevent retaliation and interrupt the cycle of violence by responding to gunshot, stabbing and blunt trauma patient during a “teachable moment.”

- Hospital case managers provide support to trauma patients to coordinate long-term recovery, community-based support and make referrals to outpatient counseling, employment resources and education services to prevent reinjury or retaliation.

Violence is just like any epidemic

Increasingly, people are referring to violence as an epidemic and as a public health problem. There is a much deeper and more meaningful truth in classifying violence in this way. Violence exhibits all the population characteristics of epidemic diseases attributes such as clustering, spread and transmission. Further, like any contagious process, past exposure to violence is the strongest predictor of violent behavior, with each violent event representing a myriad of missed opportunities for prevention. This new understanding of violence must now transform how we as a society view and approach violence.

This type of new understanding and approach — from a science and health perspective — has been used before to solve previously stuck problems. Long ago, other epidemics ravaged many areas of the world, killing millions. There seemed no end in sight and the thought of a world without these deadly problems likely seemed impossible at the time.

Thankfully, scientific discovery revealed these diseases for what they are by uncovering the invisible microorganisms that cause them. This revelation allowed us to understand these problems — as well as the people afflicted — differently, and to design new methods and strategies to stop spread. These methods have developed over several decades and in some areas of the world have successfully eradicated many of the deadliest epidemic diseases.

Invisible contagious brain processes are even more difficult to view than microorganisms, yet scientific discovery has revealed the existence of these processes and their contagious nature. And just like the discovery of microorganisms, this new information has the potential to dramatically alter how we approach violence. Understanding that violence is a contagious health problem allows for new epidemiological and public health approaches to treating violence.

To achieve the promise that this new understanding and approach hold and stem the harms and inequities of current misguided practices, we must now shift the narrative about violence toward health and contagion. Furthermore, we must implement policies and approaches that support health and community-based approaches, the same methods that have worked to address other contagious problems.

To date Cure Violence Global and its partners have successfully applied this approach to community violence, cartel and tribal violence, election violence and prison violence, and have also been piloting the approach to situations of mass shootings and to conflict zones. With more widespread understanding and implementation of health approaches, more thoroughly built-out health systems to address violence and further development of these methods, violence can be reduced to much lower levels in our communities and in our world — and perhaps, as for other ancient problems in our history, even to rare events.

Dr. Gary Slutkin is a physician and epidemiologist formerly of the World Health Organization, the founder and CEO of Cure Violence, and an innovator in epidemic management, public health, behavior change and data-based approaches to local and global problems.

Charles Ransford is the senior director of science and policy for Cure Violence, where he leads Cure Violence’s movement to make violence a health issue, oversees all research and development projects, and plays a central role in the development of the organizations strategic and operational plans.