Paul Nyhan

Poder in Action, a grassroots organization in Phoenix, works with families who are building a more just and equitable society.

Marguerite Casey Foundation

PHOENIX — When someone broke into Viri Hernandez’s West Phoenix home in 2012, she called the police. But she quickly realized the officers who knocked on her door about an hour later weren’t really interested in investigating the break in.

Instead, the officers questioned Hernandez. Where was her ID? Why was she showing them a Grand Canyon University ID, a passport and a document from the Mexican consulate? Hernandez didn’t have what the police wanted because she was undocumented and in limbo, waiting for the recently enacted Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) program to begin. And she was scared.

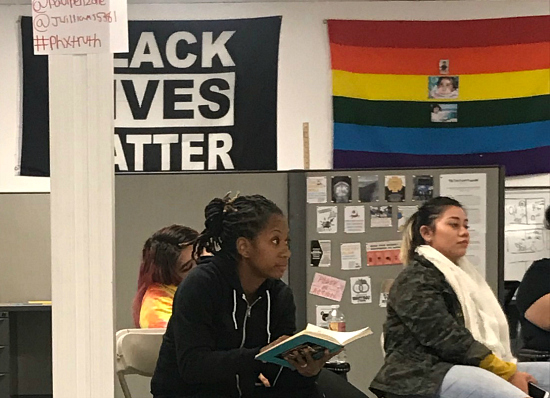

Paul Nyhan

Poder’s community college organizer Parris Wallace at a staff meeting.

Poder in Action’s work reaches college and high school students, mothers and daughters, teenagers, millennials, middle-age parents and more. And from its leadership to its volunteers, the organization is approximately 90 percent women.

Hernandez had been scared for nearly two decades. Living undocumented in Arizona had cast a shadow over her life since she arrived as a toddler with her mother from Jojutla, Mexico. At 19, she didn’t always feel safe at school, in stores or even in her own home. When Hernandez looked around her Maryvale neighborhood, she saw that same fear etched on the faces of neighbors, friends and classmates.

But Hernandez knew her rights. “You should leave if you are not going to take my police report,” she told the officers. They stayed and took a report.

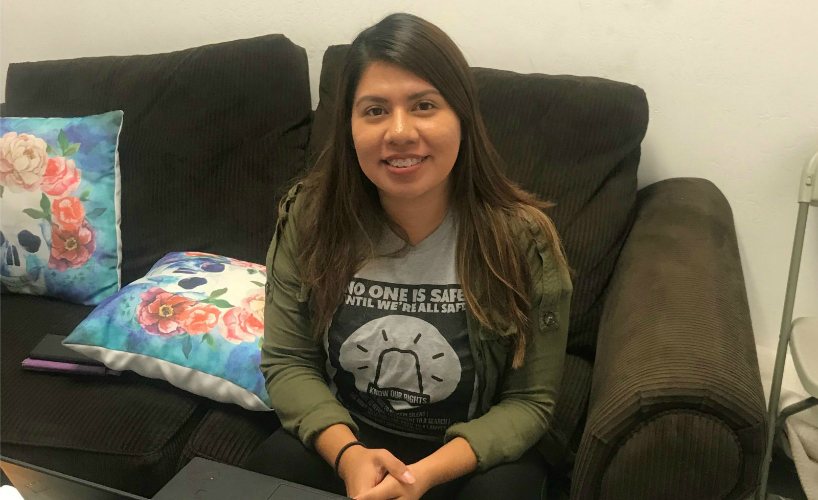

Paul Nyhan

Viri Hernandez is executive director of Poder in Action.

Hernandez knew her rights because she had been working on City Council re-election campaigns, leading civic actions and attending know-your-rights clinics for the last year. The work revealed rights that had been hidden by that shadow of fear.

“I wasn’t just undocumented. I wasn’t just young. I wasn’t just a woman,” Hernandez said. “All of those identities were actually very powerful. It is very much a process where…you have to realize your own power.”

In the five years after her house was broken into, Hernandez realized that power, as she rose through the ranks of a grassroots organization, from volunteer to paid staffer to policy director. Then, in 2016, she became the executive director – when she was just 25.

In her work, Hernandez saw that those targeted by unequal systems of criminal justice, immigration and education – including people of color, members of LGBT communities and families of mixed or undocumented immigration status – were the most capable of changing those systems.

Today, Hernandez is surrounded by people doing just that as executive director of Poder in Action. Poder is led by one-time volunteers who are challenging how Phoenix polices people of color and marginalized communities, creating safer and fairer schools and colleges and helping families understand and exercise their rights. Hernandez and other members were inspired, in part, to join the work by the 2010 enactment of SB 1070 in Arizona, seen as a harsh anti-immigrant law.

Unapologetically Building Power

Tucked in the corner of a West Phoenix strip mall, Poder in Action is a nerve center for a new generation of grassroots organizers like Hernandez, who live with the barriers they are fighting to dismantle. They are undocumented and documented immigrants, gay, straight, mothers, daughters, brothers, Brown, Black, White, students – lots of recent and current students – and nearly all women.

“[We] come into this space because we are scared of something,” Hernandez said. “We have lived in fear our whole lives. We know what that feels like. And we are now experiencing what power feels like.”

In its day-to-day work, Poder helps families protect themselves from police violence and unfair immigration enforcement, works with students to create fairer and safer schools and empowers college students. That includes those trapped in limbo as their DACA status is threatened by the Trump administration.

The work is focused on helping all of them understand their rights in a state and country where they face threats of being locked up, deported and forced to the margins of society. Poder is part of a broader movement dedicated to helping those hit hardest by oppressive systems realize they are best positioned to build more equitable communities.

“We wanted to be unapologetic to say we are building power,” Hernandez said. “Being women, young and previously undocumented, the identity of our people who are part of Poder, other people don’t see it as a strength…But people who are impacted by these systems are the most equipped to imagine a new reality.”

That imagined reality is a city with immigration, criminal justice and education systems that work for all of Phoenix’s families. But first, members are applying Poder’s mantra – disrupt, dismantle and determine – to the status quo.

One November morning they disrupted rush hour by hanging banners marking the latest police-related shooting from highway overpasses. Later that day those banners were draped in front of City Hall. Another day, they talked about inequitable policies in meetings with Phoenix’s city planner and City Council members. And they continually work to develop the next generation of leaders among the youth of Maryvale, the predominantly Latinx neighborhood Poder in Action calls home.

Paul Nyhan

Members of Poder in Action work on a banner to mark the 40th police-involved shooting in Phoenix.

A big part of Poder’s work is challenging myths that threaten families and communities in this city of more than 1.6 million people. Kate Tutaya, Poder’s former head of communications, named one of the most dangerous myths: That Phoenix’s undocumented community is a “small, rogue, violent population that is here without papers.” That myth forces parents and children to live in fear of being detained and torn from their families – and keeps many from going to hospitals, the police and even banks.

Like all myths, this one isn’t true. But it can overshadow the reality of Phoenix’s immigrant community: families working, supporting the region’s economy, raising their children and building a future in which they have a say.

“If you are anyone in Phoenix, you have friends who are undocumented,” Tutaya said. “That is not the story they tell. The undocumented community out there is strong and thriving and alive.”

Poder in Action wants to bring that reality out of the shadows by changing how people think of what it means to be undocumented, safe, policed and members of a community. Instead of living in fear, Potter’s members are fighting to control their story – telling who they really are, not who they are portrayed to be.

“People who are talking about the issues and pushing policies are not the people who have been affected,” Hernandez said.

Poder in Action’s work reaches college and high school students, mothers and daughters, teenagers, millennials, middle-age parents and more. And from its leadership to its volunteers, the organization is approximately 90 percent women.

This flips a traditional power structure in Phoenix, where volunteers and staff at grassroots organizations have been predominantly women, but those making decisions have been largely men, Hernandez points out.

This switch “definitely has something to do with our success,” she added.

Power at Four Folding Tables

If you want to understand Poder in Action, sit down at its community desk, really four folding tables pushed together in the middle of its wide-open office space. The community desk is littered with cartons and bowls of food, burnt sage, papers, smartphones and laptops.

It’s an organic but organized hive where everyone eventually sits during the day, from Potter’s director to its volunteers. It’s where they talk about everything: upcoming meetings, painting Potter’s values onto the walls outside the office, the latest twists in their relationship with the city’s police chief, and the upcoming NCAA bowl game.

Amid this ever-present buzz, Viri Hernandez works with Poder’s community college organizer Parris Wallace on a PowerPoint presentation for their upcoming meeting with Phoenix’s city planner. They plan to push for a participatory budget that would give Maryvale’s residents a say over how to spend a slice of Phoenix’s public dollars.

A Map, a Whiteboard and a Future

Looming over all of this at the front of the room are two guideposts: a giant whiteboard and a map with a growing number of pushpins.

The whiteboard holds a handwritten timeline of Poder in Action’s recent progress and its plans for the coming year, which include targeting the city budget process, state legislative session and upcoming negotiations over a new union contract for the city’s police officers. It’s the communal brainchild of a recent staff meeting.

The map, on the other hand, is both a memorial and a reckoning, where pushpins and colored index cards mark 40 police-involved shootings – a record for the city.

Together, the map and whiteboard represent the two sides of Poder in Action. One holds the tragic fallout from the oppression it’s fighting. The other is the latest draft of its plan to dismantle systems of that oppression and create a more equitable city.

While that oppression dates back generations, Poder in Action is less than a year old. The organization was born from what was the Center for Neighborhood Leadership, which itself was about four years old.

After spending a year rethinking its work, members and staff created Poder in Action from the bones of the Center. Poder would be hyperlocal – based in the Maryvale neighborhood of West Phoenix that it represents – and committed to creating power and change, while also “focusing on leadership development, systems change and local public policy.”

The move to Maryvale reflected Poder’s focus on helping families, including the undocumented, go from living in fear to recognizing and using their rights.

“A big part of it, leadership development, is trying to get a high school student, undocumented mother or a community college student to find their power and feel ownership over the political process in Phoenix,” said Tutaya, Poder in Action’s former communications leader.

‘We are making them change’

Poder in Action is beginning to lay groundwork to dismantle at least portions of what many see as the city’s inequitable systems.

In mid-November, for example, Viri Hernandez reported the city planner was interested in a participatory budget, one that would give Poder’s members and Maryvale residents a voice in the budget process.

By January, city officials had asked Poder to join an ad hoc committee to explore the city’s responsibilities in officer-related shootings and the issue of police brutality.

It’s only a beginning, but one that’s hopeful and a bit startling, coming from a state that’s an epicenter of one of the most anti-immigrant periods in modern U.S. history.

These sometimes-quiet changes aren’t coming from within the chambers of the Phoenix City Council or the mayor’s office, though.

The changes echo the thinking of those at Poder in Action.

“They are not changing,” Hernandez said. “We are making them change.”

Paul Nyhan is the storytelling and partnership manager at Marguerite Casey Foundation.

See the original article here.

This article was written for Equal Voice, Marguerite Casey Foundation’s publication featuring stories of America’s families creating social change. With Equal Voice, we challenge how people think and talk about poverty in America.