Photo illustration by Yunuen Bonaparte

.

Foster youth who identify as LGBTQ face significantly more hurdles in their educational path, experiencing harassment, homelessness and depression at higher rates, but researchers don’t have enough data yet to determine the impact on their high school and college graduation rates.

“These young people have experienced so much failure and setback … They urgently need our help,” said LD Thompson, founder of Sanctuary Palm Springs, a home for LGBTQ youth transitioning out of foster care.

Until recently there has been little research focusing on this group of foster youth because federal laws don’t yet require social service workers to gather information about foster youth’s sexual orientation or gender identity. The data that does exist, however, shows that LGBTQ foster youth tend to show lower school functioning due to greater instability in their lives than other foster youth.

Estella Delgado, a student at Fullerton College and a former youth in care who is lesbian, said she used to think about dropping out in high school, but decided college was the only way to overcome a life of poverty. Delgado, 20, struggles with similar challenges as other foster students, such as not having any family, but what she finds the most challenging is dealing with prejudice and harassment for being lesbian.

“Since I was in high school, there were always guys who thought I chose to be lesbian and made stupid jokes about it. One guy even tried to kiss me and was touching me everywhere,” said Delgado, who cited a hostile home environment as the reason she ended up in foster care.

UCLA School of Law

Bianca D.M. Wilson

Many LGBTQ youth end up in foster care due to lack of acceptance from their own family about their sexual orientation or gender identity. They often fail to find that acceptance in foster care. That lack of acceptance forms the root of other disparities they experience that affect their schooling, such as harassment and high rates of school absenteeism, according to a study published in Pediatrics in February.

“Finding that they experienced the system itself as harsher or less positive is important for us to keep in mind,” said Bianca D.M. Wilson, a public policy expert on lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender issues at UCLA School of Law’s Williams Institute who collaborated on the Pediatrics study. “It’s not just about how they got into the system, it’s also about figuring out a way to make sure that their experience in the system is respectful and affirming, and we do need to make sure that they find a permanent home.”

High percentage in LA

The 2018 California Children’s Report Card assigns a grade of D+ to the state’s education support for students in foster care, citing the fact that foster youth change public schools an average of 3.5 times in the first four years of high school. Only about 50 percent of California’s foster youth graduate high school, with a tiny fraction of those getting a college degree by the time they’re 26 years old. Whether LGBTQ foster youth as a group fare similarly, better or worse in terms of educational attainment remains unknown.

However, Wilson’s research does show that LGBTQ youth are overrepresented in foster care in Los Angeles and urgently need care that is more supportive of their sexual orientation and gender identity. In Los Angeles County, nearly 20 percent of foster youth identify as LGBTQ. The Pediatrics study surveying California middle and high school kids found that as many as 30 percent of foster care youth could be LGBTQ.

Seven states have laws that are considered harmful for LGBTQ youth in schools. California is one of 18 states with laws designed to protect LGBTQ youth in schools from discrimination and harassment due to their sexual orientation and gender identity, but this hasn’t always translated into effective policies.

“A teacher once told me it would be better if I didn’t tell people I’m gay,” said Jed McDonald, a Pasadena City College student and former youth in foster care.

“I think she meant it as helpful advice because she wasn’t a mean teacher, but it didn’t feel that way,” Many LGBTQ youth have lower grade point averages and are more likely to consider dropping out of school due to harassment or a school climate they perceive as hostile, according to the 2017 School Climate Survey conducted by GLSEN, a nonprofit advocate of LGBTQ issues in education.

In California, a pending bill aims to bolster existing laws to help California’s schools create a more supportive environment for LGBTQ youth. The Safe and Supportive Schools Act would require all school districts to provide annual training for teachers to learn how to better support LGBTQ students.

Emerging Arts Professionals

Shani Heckman

San Francisco filmmaker Shani Heckman is one of a small percentage of former youth in care who have earned a master’s degree. She found that her success relied on hiding that she’s a dyke (her chosen term; she considers lesbian a classist label). Heckman, 49, earned her bachelor’s degree in global economics from University of California, Santa Cruz in 1995, a time when there was less awareness about the needs of youth in foster care and even less about those of LGBTQ youth.

She became an orphan at 13 after both her parents died, leaving her with a small trust fund and the dream of going to college. While she was in foster care, someone from DeVry University showed up at her Delaware group home to recruit students. She signed up.

“I was lucky that I came from an upper-middle-class home. My mother had always told me she wanted me to go to college,” Heckman said.

The small trust fund was just enough to pay for her first year of college there. She later transferred to UC Santa Cruz. She remembers falling into a deep depression while studying abroad in Italy, watching fellow students receive care packages while her mailbox remained empty. Heckman remained closeted, feigning interest in men and going on “fake dates.”

Helping those behind her

After graduation, Heckman thought about how difficult her journey had been.

She had to push for her group home to allow her to attend a traditional high school, where she could take academically challenging college-prep courses that would help her stand out to colleges. Normally the home required all its foster youth to enroll in tech school, whose graduates did not tend to go to college, she said.

Heckman became determined to help other foster youth have a better path in college.

“The college route was never something that was offered to foster youth,” she said. “It was something you had to fight for.”

For her master’s in filmmaking, Heckman focused on the lives of four California LGBTQ foster youth in her 2012 film “America’s Most Unwanted.” The film offers an intimate view into the lives of these youth as they grapple with challenges such as homelessness, prison time and suicide attempts. It also depicts their successes as they overcome these challenges in various ways, including one who writes a book and others who go to college.

University of Chicago

Matilda Stubbs

Anthropologist Matilda Stubbs shows the film to social workers and other students in classes she teaches at the University of Chicago and other colleges as an adjunct instructor. She has the rare perspective of a former foster youth who never had a permanent home, combined with being an academician.

From infancy through her senior year in high school in 2001, she was in the foster system, with her last bed a living room couch at a friend’s house while she worked two jobs.

Stubbs spent years researching the bureaucracy of the foster care system. She knows well the deficiencies of being a child in care, understanding exactly how “it all impacts your ability to go to class and focus.”

“Foster youth are held up to this ridiculous standard,” she said. “If they mess up in any way, they’re immediately labeled as pathological.”

Stubbs had two stabilizing forces in her life. As an elementary school student, she signed herself up for the Girl Scouts, and now has a tattoo to symbolize her life membership and the lifelong friends she met there. And she credits UC Santa Cruz’s Smith Society with creating a community that helped her and other foster youth thrive in college.

“There are people doing great things, but the great things they’re doing aren’t getting the leverage they should,” she said.

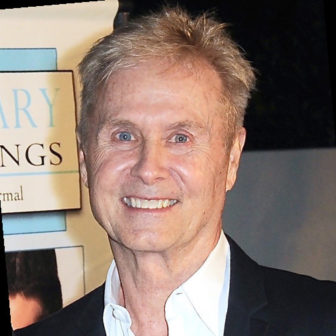

LD Thompson

Sanctuary Palm Springs runs on a program founders Thompson and David Rothmiller created that stresses education, while offering services specifically designed for the needs of LGBTQ foster youth. It’s a state-licensed home for LGBTQ youth aging out of the foster care system at 18 to 21 that opened its doors about two years ago.

Former foster parents for LGBTQ youth in Washington and California, they knew many of these youth lacked homes where they felt accepted and could learn how to become self-sufficient adults.

They think the home, which has a live-in staff of eight, is the only one of its kind. Calls from Louisiana, Michigan and Mississippi have asked for help to replicate their program, Thompson said.

And in Los Angeles County, the 2014 Williams Institute study prompted officials to assess how well it was serving LGBTQ youth and prescribe solutions to deficiencies, a process that is still ongoing.

LA County has the largest population of foster youth in California. The state has the largest foster youth population (about 49,000) in the country.

“We have policies. We have verifiable data. Folks are actually attempting to do something,” said consultant Khush Cooper, who has advised LA County on its agencies’ awareness and ability to meet the needs of LGBTQ youth. “Are we there yet? No. But it’s very different than 10 years ago when people weren’t even aware that they were serving LGBTQ youth.”

This story is part of a Youth Today yearlong project on youth transitioning out of foster care. It’s made possible in part by The New York Foundling, which works with underserved children, families and adults with developmental disabilities. Youth Today is solely responsible for the content and maintains editorial independence.