Reuters/Edgard Garrido

Daily life in some parts of Central America is so fearsome for parents and children that crossing Mexico and risking detention in the U.S. seems less fearsome.

Gang violence and expanding criminal networks have made El Salvador, Honduras and Guatemala — an area of Central America known as the “Northern Triangle” — some of the world’s most dangerous countries.

El Salvador’s homicide rate in 2016 — 109 murders per 100,000 people — was more than 25 times that of the United States. It was almost triple New York City’s homicide rate during New York’s bloodiest years in the 1970s and 1980s.

Murders have generally declined across the Northern Triangle in recent years. Yet thousands of Central Americans each month make a risky trek across Mexico to seek asylum in the U.S from what is still pervasive violence in their home countries.

The continued influx spurred Attorney General Jeff Sessions to say “the immigration system is being gamed,” suggesting that migrants were only pretending to flee violence to gain asylum in the U.S. The Trump administration has adopted a “zero tolerance” policy of arresting and prosecuting all migrants as criminals.

But life is actually getting more dangerous for some Central Americans: teenagers.

Why families and children flee

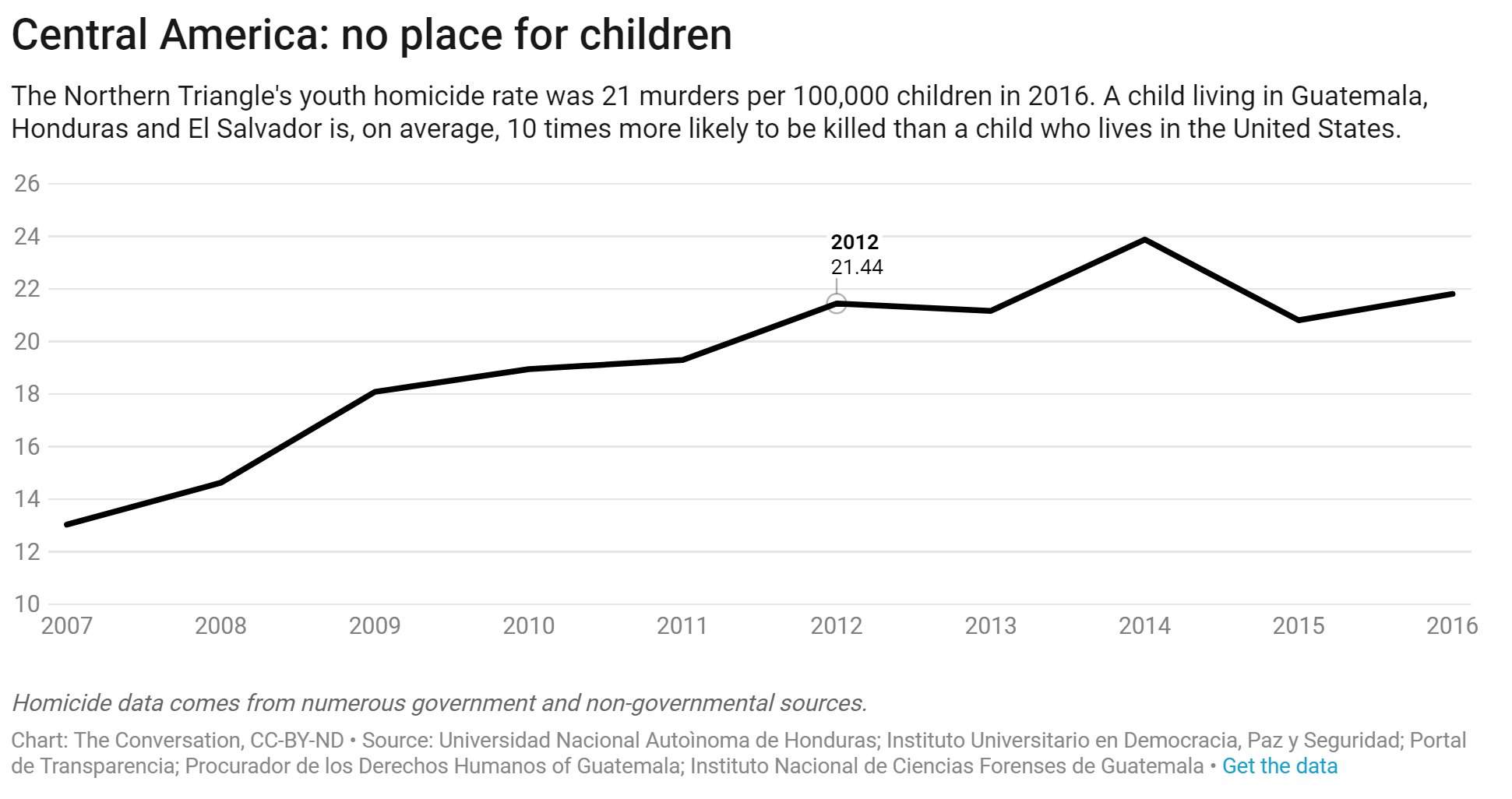

My research in the Northern Triangle shows that homicide rates among people aged 19 or younger have been steadily rising since 2008. Youth homicides in the region are now over 20 per 100,000 — that’s four times the global average.

Put another way, Central American children are 10 times more likely to be murdered than children in the United States. Kids aged 15 to 17 face the highest risk of death by homicide.

I believe this disturbing, little-discussed trend explains why so many families and young people continue to arrive at the U.S. border, despite knowing the perils that await them on their journey and in U.S. immigration courts.

Children in Honduras, El Salvador and Guatemala are in so much danger that crossing a thousand miles of Mexico — a journey during which 60 percent of women and girls will be assaulted physically, sexually or both — apparently seems like a better bet.

I already knew from other research that an increase in overall violence in the region causes additional unaccompanied child migrants. To find out whether record-high youth murder rates were impacting migration patterns among children and families, I paired U.S. Custom and Border Protection data on over a million individual apprehensions with homicide data from the Northern Triangle and Mexico.

The results suggest that targeted violence against children is the main reason that families and unaccompanied minors decide to migrate.

Central American children traveling without their parents first began arriving en masse at the U.S.-Mexico border in 2009. That year, roughly 8,000 northern Central American unaccompanied minors were caught crossing into the United States unlawfully, according to U.S. Customs and Border Protection data.

Back in the Northern Triangle, violence against young people was starting to rise, too. In 2007, 13 children were killed for every 100,000 in the region. By 2009, the figure was 18 per 100,000.

The homicide rate among people 19 years or younger spiked in 2014, rising 12 percent to 24 murders per 100,000. That’s six times the U.S. national homicide rate.

Up at the U.S.-Mexico border, the number of families and solo children apprehended likewise increased, by 40 percent.

The next year, in 2015, child homicide rates in Central America declined 13 percent. Apprehension rates at the U.S.-Mexico border dropped back to pre-2014 levels, down 40 percent.

Excluding other drivers of migration

My analysis on child and family migration controls for other reasons people might decide to go to the United States, such as generalized violence, poverty and family networks.

I also tested alternative explanations for migration patterns among young people and families, such as changes to U.S. legislation that might make migrating more appealing or sudden economic opportunity for migrants. The timing did not line up for either.

These and other factors certainly do figure into Central American migration trends. Child murder rates in the Northern Triangle do not explain all migration among young people and families.

But I believe they are the driving force behind it.

Reuters/Jorge Lopez

Parents who’ve seen children buried may see the perilous journey through Mexico and the US as their only chance at safety, despite the ever-rising risks.

Why deterrence won’t work

Consecutive U.S. presidents have tried simply to stop asylum-seekers by making migration to the U.S. unappealing.

Faced with an influx of unaccompanied minors, President Barack Obama in 2014 began putting families in detention centers in New Mexico. The U.S. also enlisted Mexico in its immigration enforcement efforts, funding an aggressive security initiative to prevent people from crossing Mexico’s southern border with Guatemala.

Migrant numbers have risen and fallen since then, but the trend among children and families is upward.

An estimated 8,391 families and 15,625 unaccompanied minors were apprehended at the border in 2011. Six years later, in 2017, these numbers had increased to 63,411 families and 33,012 solo children, according to Customs and Border Protection data.

The Trump administration has taken an even more punitive approach to immigration, including separating children from their families. Yet 2018 is currently on track to break last year’s record for the total number of migrant families and children apprehended at the border.

My study suggests that virtually no immigration policy could scare some Honduran, Salvadoran and Guatemalan parents more than everyday life already does.

Ultimately, securing American borders will mean making the most vulnerable citizens of Honduras, Guatemala and El Salvador more secure, too.

Julio Ernesto Acuna Garcia is an assistant professor in the economics department of the Universidad San Francisco de Quito in Ecuador.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

![]()