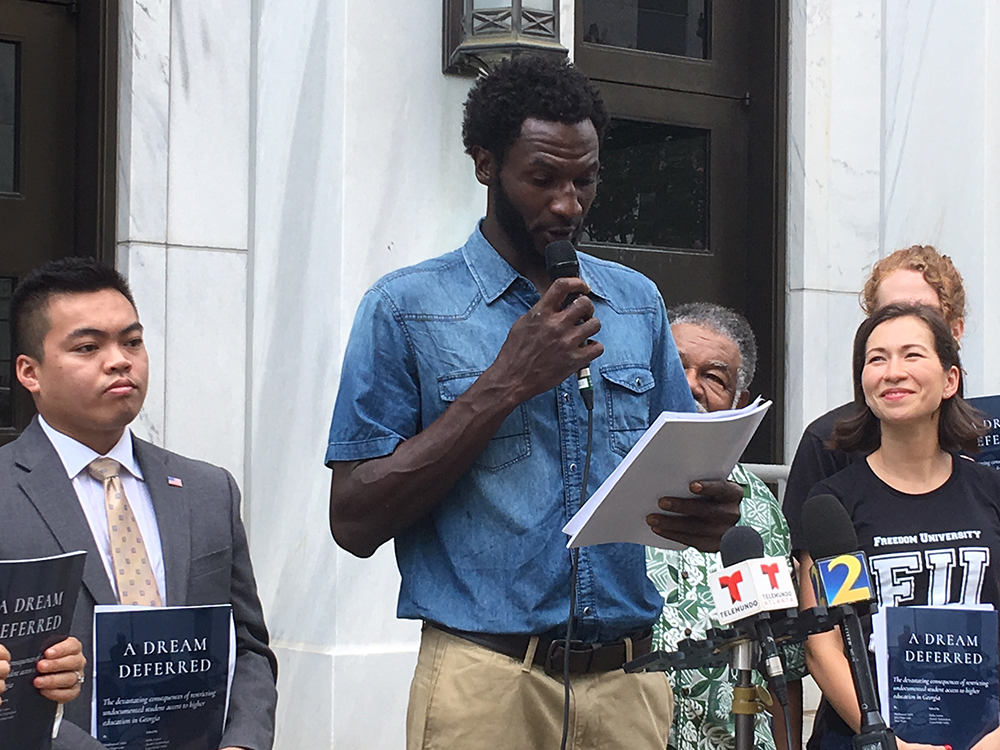

Photos by Stell Simonton

Mamadou Diakite, 28, spent his 20s working in road construction after losing a college scholarship because he was undocumented.

When Mamadou Diakite was a sophomore at a small Georgia public college, he lost his scholarship. Officials from the national science organization that awarded it found out he was undocumented and revoked it. His college career came to a halt.

At age 11 months, Diakite had come with his parents to the United States from Mali, West Africa.

He grew up in Georgia, graduated from Riverdale High School in Clayton County and, in his mind, was “a normal American kid.”

But he experienced one of the many obstacles undocumented students face in Georgia — where about 3,000 graduate from high school each year — and across the nation. Georgia is one of the three most restrictive states, prohibiting undocumented students from attending certain public colleges and requiring them to pay out-of-state tuition at others.

When access to higher education is made so difficult, what happens to these students?

“They overwork in low-wage jobs,” said Laura Emiko Soltis, executive director of Freedom University.

Diakite, now 28, has worked in road construction since leaving college.

They also battle depression and fear, she said. Freedom University is a “freedom school” founded in Athens, Ga., in 2011 that offers free courses to undocumented students and assists them in gaining scholarships.

Poor advice

A new report from Freedom University and the nonprofit Project South details the impact of barriers to higher education for undocumented students. The report, “A Dream Deferred: The Devastating Consequences of Restricting Undocumented Students Access to Higher Education in Georgia,” was unveiled in Atlanta.

Students lose motivation and come to feel there is no point in doing well in school, the report said.

Some evidence shows that young women are particularly affected, facing more pressure to marry or go into low-paid domestic work.

[Related: Scholarships, Financial Aid Available for Undocumented Students in Some States]

Guidance counselors and college admissions officers are often ill-informed and unable to advise students effectively, according to the report, and the financial hurdles seem insurmountable.

The University System of Georgia issued a statement in response to the report, saying that Georgia policies on undocumented students comply with federal and state laws and mirror guidance from the office of the attorney general.

“These laws require public higher education — including the University System of Georgia — to ensure that only students who can demonstrate lawful presence are eligible for certain public benefits, including in-state tuition or access to institutions that admit students on a competitive basis,” the statement said.

Arizbeth Sanchez, 24, speaks at a press conference in Atlanta, explaining how she was affected by being unable to go to college when others in her high school graduating class were headed there.

Erosion of confidence

“I wish I could have gone to college with my peers,” said Arizbeth Sanchez, 24. She was an excellent student and attended Norcross High School in Atlanta.

But the barriers to college came as a shock. The law requiring her to pay out-of-state tuition was a giant roadblock, she said.

“I couldn’t understand it,” she said.

Sanchez took classes at Freedom University and now works there as community engagement and volunteer coordinator.

“The hardest part … is not blaming yourself,” she said. She remembers hearing teachers encourage students by telling them they could do anything. But when students can’t move ahead in their education, they wonder what’s wrong with them.

It creates a sense of “internal shame,” Sanchez said. Students question whether they really have worked hard enough, she said.

Raymond Partolan, 25, came to the United States with his parents from the Philippines when he was little more than 1 year old. His father was a physical therapist and sought permanent residency.

But when Partolan was 10, his father’s green card application was denied.

“I was plunged into undocumented status,” he said.

Suicide attempt

“My mom instilled in me the value of education,” he said, but by his junior year in high school, he realized that no matter how hard he worked he might not be able to go to college.

That was the year he tried to kill himself.

“I didn’t feel like I belonged here,” Partolan said.

What helped him climb out of the darkness was to start talking with others about how he felt.

Expressing his feelings with others took a burden off him. “It showed me people actually did care,” he said.

Partolan applied to 14 colleges and received a full scholarship to Mercer University in Macon, Ga., where he became the student body president.

He now works as a paralegal for attorneys Kuck | Baxter Immigration and hopes to go to law school.

Diakite, who lost his science scholarship, returned to school via Freedom University, where he took biology classes, last year. The school helped him gain a full scholarship to Delaware State University, where he will begin classes in 2019, studying sustainable urban agriculture.

His view about the barriers undocumented students face:

They label us as criminals and make us hate ourselves, he said. “We’re not meant to succeed.”