Photos by Clarissa Sosin

New York City Chief of Detectives Dermot F. Shea testified at City Hall in Manhattan Wednesday about the NYPD’s gang database. This was the first hearing to provide transparency into the controversial database.

NEW YORK CITY — Ninety-nine percent. The number sent an audible gasp throughout the City Council chamber. Chief of Detectives Dermot F. Shea had just read off the percentage of people of color on the NYPD’s controversial — and until now — largely secretive gang database.

Shea was talking publicly for the first time about one of the New York Police Department’s most popular crime-fighting tools. He testified Wednesday before the City Council’s Committee on Public Safety in the database’s first comprehensive public examination.

Shea read the numbers from a stack of papers in front of him.

African Americans: 65 percent.

Non-white Hispanic: 24 percent.

Black Hispanic: 10 percent.

Shea said the gang database, whose number fluctuates as names are added and purged, stood at 17,441. Given those percentages, that means 17,267 of the individuals in the database are either black or Hispanic. Earlier in the morning critics rallied to protest the use of the database, saying it’s racist.

There are 1,460 people who are younger than 18 in the database. In response to questioning, Shea said there are 17 13-year-olds, 80 14-year-olds, 204 15-year-olds, 455 16-year-olds and 704 17-year-olds. “You can see how the number goes up as they get older,” he said. The average age of someone on the database is 27, he said.

Public Safety Committee Chair Donovan Richards, who led the hearing about the database, was doubtful about how the innocent could avoid being included.

The NYPD, which encompasses the largest detective bureau in the country, has no formal process for notifying parents whose children are in the database. But, he said, there are a number of informal ways that parents are alerted.

“I don’t want to make it seem like there is no interaction with the parents,” Shea said. “Nothing could be further from the truth.”

Click here for more New York gang-related coverage

Youth officers assigned to precincts and to transit and housing units might talk to the parents during the course of an investigation and the topic might come up then.

How does someone end up on the database, Public Safety Committee Chair Donovan Richards asked.

There are a number of ways, Shea said: One is what he described as self-admission. This often happens on social media, where gang members may talk about their affiliation, he said. Another is through two independent sources who tell a member of the department. That name then needs to be vetted by investigators. Anyone can be a source of that information — friends, teachers, family or a confidential informant.

Finally, he said, gang investigators can identify the presence of gang literature, tattoos, colors, clothing and other means of what they think is an indication of gang affiliation.

The gang database was more than a bloodless policy discussion to him, Richards said: “When I was 14, I could have been in this database.”

His parents sent him to reform school, and that’s why he was sitting in City Hall. He said he worries that mere presence on the database could derail a young person on the fringes and condemn them to a life in the criminal justice system.

Without adequate resources, often no community center, no programs and no opportunities for employment, young people are left with little choice.

“They go out there and want to be part of something,” Richards said.

A crowd of activists gathered outside City Hall in Manhattan before the Public Safety hearing about the NYPD’s gang database.

The genesis of the turn toward gangs

In 2014, the year the NYPD conducted what was then the largest raid in history in the Grant and Manhattanville housing projects in Harlem, the database was twice as big, containing 34,000 names, Shea said. It’s a credit to the NYPD’s commitment to precision policing that it has winnowed the database down by half, he said.

People on the database are reviewed every three years to see if they still deserve to be there, Shea said. Everyone is reviewed on their 23rd and 28th birthdays. If the department feels the person has abandoned the gang and taken what he called a “different path of life,” then the department purges them from the database.

Richards said he was concerned that the NYPD does not do enough to ensure that the database does not sweep up names of people who are innocent. He kept returning to a hypothetical of someone wearing a blue cap and jeans and sneakers who walks to his local bodega to buy a bagel. If that person shakes hands or chats with someone on the database, what’s to prevent that person from being placed in the database with no knowledge of it, he asked.

The question was not an abstract one, he said. Being in the database can come with serious and possibly catastrophic consequences. Immigration authorities can use it for deportation. Prosecutors can use it to set higher bail or remand, so someone can end up marooned on Rikers Island for a minor crime. And judges can consider placement in the database during sentencing, even for nonviolent offenses, Richards said.

The hearing put in sharp relief a debate about the future of policing in New York City. The gang database has been an object of mystery to the public and of ire to critics. They say the raids, mostly of housing projects, are a mutation of the stop and frisk tactics that public opinion, politics and judges had said had become untenable as a law enforcement policy.

Defense attorney Jason Martin called the database “an old Jim Crow-era tactic.”

A technological twist on an old policy

The NYPD made one argument inside City Hall. The database is essential for what they call “precision crime fighting.” For a person to be placed in the database, the department goes through a rigorous process to ensure it is not bloated with innocent people, Shea said.

As for its necessity, he played a series of security camera videos. They played one after another, silently displaying grainy bouts of mayhem. One showed what he described as a gang member shooting indiscriminately in the street. Another showed a shootout in a convenience store. A third provided a tilted look at a shooting in the middle of the day. One bullet struck a man pushing a stroller.

The victim survived, but Shea asked the audience to consider what would happen if the bullet took a slightly different trajectory.

Outside, a very different case was being made by protesters, civil rights activists and people who have been swept up in the NYPD’s gang raids.

One man talked about how he was on the database in 2011. He remembers the police destroying his apartment and traumatizing his family while he waited outside in cuffs. He said his mother and siblings were homeless for years afterward.

Another said he was 16 when he was wrongly arrested because of his affiliation with someone who was on the database. He spent three years in six different upstate prisons. He came back home disgusted with the system. Another said he was recently pulled over during a routine traffic stop. He said after the police officer ran his name they told him to get out of the car and put him in cuffs. He wondered aloud how badly that stop could have turned out.

Defense attorney Jason Martin has been at the forefront of police reform. He was one of the dozens of people demonstrating on Broadway at the gate of City Hall. Behind him people held up posters of a cartoon cop with a surveillance camera for a head. A warning was written on it in bold black letters: Big Brother Is Watching.

Martin said he was frustrated at how racial policing seems to mutate from one policy to another. Most recently, it was stop and frisk.

“We win one battle and here we are out here again,” he said. “This gang database — it’s an old Jim Crow-era tactic. You label a group as different, then you treat them as second-class citizens. It’s a new thing we’re dealing with, and we have no idea how far-reaching the consequences are.”

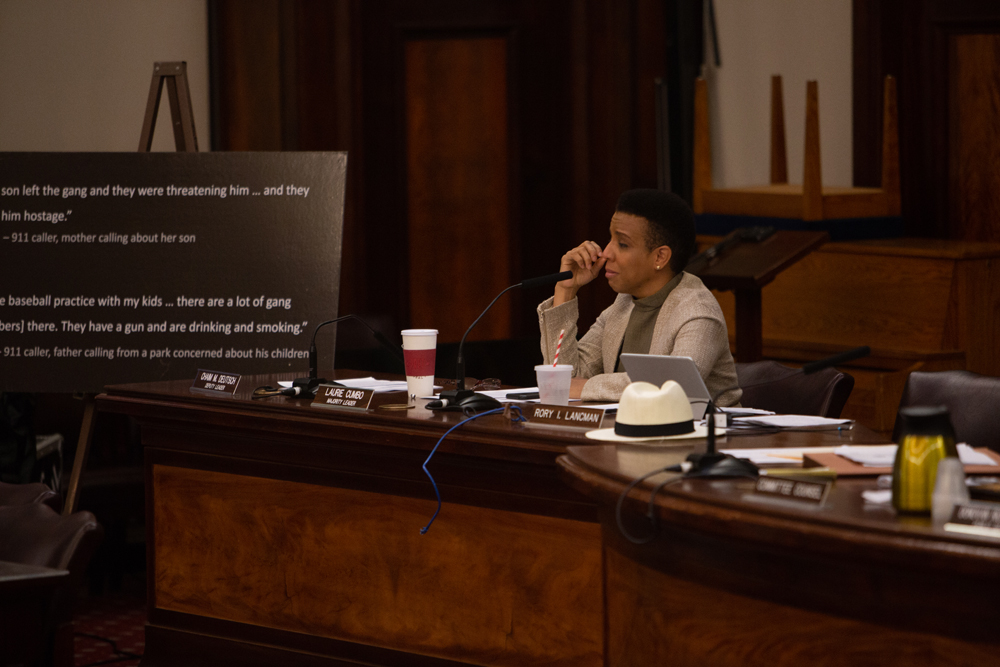

City Councilwoman Laurie Cumbo cried after asking Shea questions about the database.

An emotional day in the twilight zone

The 2014 gang raid was launched partly around the killing of Tayshana “Chicken” Murphy, a promising basketball star who was shot down in her hallway. Murphy’s brother, Taylonn Murphy Jr. was later convicted for killing one of the men thought to be involved in Tayshana’s killing. He was sentenced to 25 years to life in 2016.

In the wake of that violence, Tayshana and Taylonn Jr.’s father, Taylonn Murphy Sr. organized efforts to quell the violence generated by the feud between the rival houses.

Murphy testified in front of the city council Wednesday. He said he appreciated the platform to talk about the gang database, but said that it dredged up what he feels is the futility of years of trying to change the city’s approach to solving the problem of hopelessness and helplessness among poor youths in the city.

Echoing the concerns of other people who testified, he said the database is blunt, intrusive, too broad and a new way for the NYPD to target young people through racial profiling. He compared it to a policy from the 1850s, updated with frightening technological refinement.

“It’s putting a stranglehold on the community through police oppression,” Murphy said. “It’s targeting people living in poverty and that is unfortunate. We should be investing more in our young people. We should be cultivating the youth instead of labeling them. We need to cultivate their thinking. You do that with love and nurturing, not with harsh sentences and databases.

“I want people to start listening to the people who are on the streets and in the trenches. You can’t solve this problem from the ivory tower,” he said. “We are so hooked on policy — policy, policy, policy — that we don’t have any empathy, man. Empathy for young people. These young people aren’t subjects. They are our future.”

Later in the day after Murphy had had time to reflect on the hearing, he said, “It’s like being in the Twilight Zone sometimes, man. You want to say, ‘Don’t you see what’s going on?’ And if you see what’s going on, why can’t you do something about it? I’ve been out here beating my chest, screaming about it for years and nothing is being done.

“You stop the crime, yes, but you’re destroying generations of young people,” he said. “I know it’s a strong word, but it seems like a slow-motion genocide. If we don’t deal with these things with some kind of morality, we’re looking for a rough time somewhere down the line. You can’t expect people to do something with nothing. You are creating desperate people.”

During the questioning period after Shea’s testimony, City Councilwoman Laurie Cumbo, who represents parts of Bedford-Stuyvesant in Brooklyn, begin to speak but could not get out the words. Her voice faltered and she begin to sob.

“The words we use, the language we use,” she said struggling to articulate her point. “To hear us talk about them like this. To talk about them like numbers in a database.”

After a moment she gathered herself.

“I just hope,” she said. “My son never ends up on it.”