NEW YORK — Instead of hanging out, 35 Coney Island teenagers spent their midwinter vacation last week learning to cope with everyday trauma and avoid dating violence.

The second annual Anti-Violence Academy for teenagers and young adults was organized by the Coney Island Anti-Violence Collaborative (CIAVC), whose primary mission is ending gun violence in the Brooklyn neighborhood. It started less than a week after a 19-year-old gunman killed 17 people at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, Florida.

“We’ll definitely address the [Florida] shooting because it’s a national epidemic,” said CIAVC Executive Director Keisha Boatswain on the first day of the three-day session. “We want our young people to feel empowered and use this unfortunate tragedy as a catalyst for change here in Coney Island.”

“We’ll definitely address the [Florida] shooting because it’s a national epidemic,” said CIAVC Executive Director Keisha Boatswain on the first day of the three-day session. “We want our young people to feel empowered and use this unfortunate tragedy as a catalyst for change here in Coney Island.”

Coney Island is the birthplace of the amusement park. But beyond the beach and the boardwalk, there’s a tight-knit community where many residents feel geographically and politically isolated from the rest of New York City. The median household income here is $31,371, compared to $55,191 across New York City, according to U.S. Census figures. The neighborhood also has a legacy of gun violence that still traumatizes some residents even though the number of shootings has gone down in recent years.

Three young women take part in anti-violence training in Coney Island, Brooklyn.

“I’m scared to go outside at night, to know that people are violent and hurt other people,” said Toni, 12, an academy participant.

Shooting incidents in the 60th Precinct, where Coney Island is located, have dropped by 67 percent over the last two years, according to New York Police Department data. There has been one shooting so far in 2018 and there were two in 2017. The goal of the academy was to ensure that that trend continues.

There’s hope among the younger generation. Toni’s sister Alexis, 14, added, “If we come together as a community, violence can stop. Our community can get better if we all just stick together.”

The academy was held in a meeting space at MCU Park, the stadium that’s home to the Brooklyn Cyclones minor league baseball team. If they hadn’t attended the academy, Toni and Alexis said, they probably would have been home watching TV.

Facilitator Clifton Hall listens to a participant during the workshop on trauma.

“I commend them,” said Dale Anderson, an academy volunteer who has attended CIAVC’s Anti-Violence Academy for adults. “This academy will do so much more for them than just staying in the house. It’ll open their eyes and their minds to a different way of thinking, to a different way of seeing society, to a different way of seeing life.”

A major part of the training focused on helping the 13- to 19-year-old participants recognize the triggers, trauma or PTSD they face in their daily lives, said Boatswain, the CIAVC executive director.

“Young people in New York City face traumas every day when they enter a school building and they’re met with members of the New York Police Department,” Boatswain said. “They go through metal detectors, many of them disrobe, take their belts off. That in itself is a traumatic experience.”

In 2016, a joint investigation by WNYC and ProPublica found that black and Hispanic New York City high school students were nearly three times more likely to have to walk through a metal detector each morning than their white peers. Almost half of all black high school students across the city had to go through metal detectors compared to just 14 percent of white students, according to another WNYC analysis in 2015.

Nearly all the academy attendees were people of color, which is reflective of Coney Island’s west end.

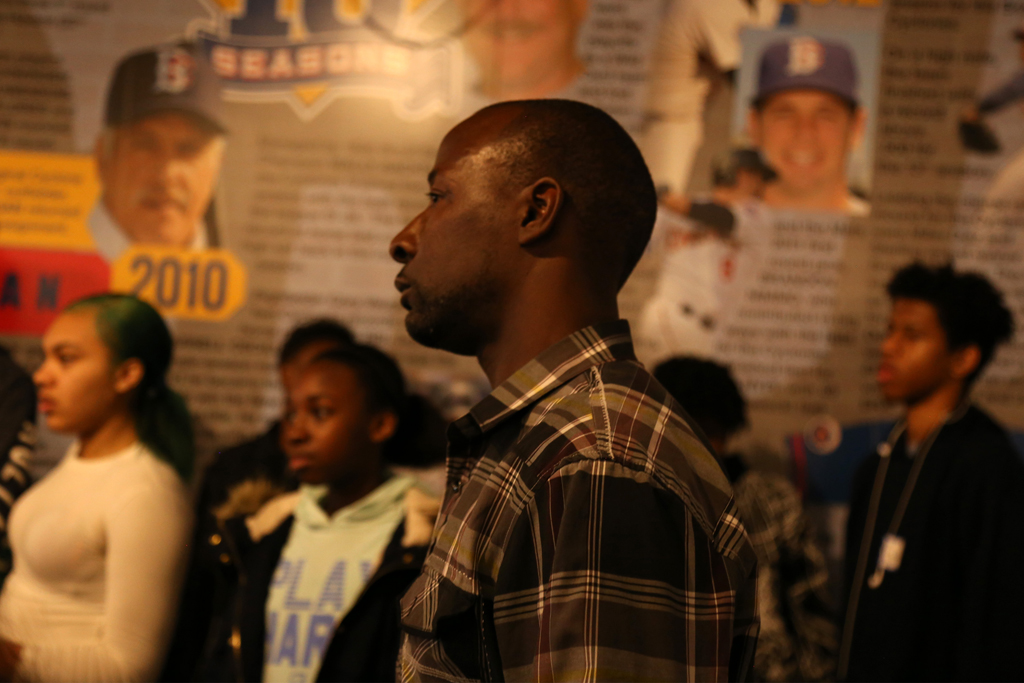

Facilitator Clifton Hall (center) leads a trauma workshop.

Carlo, 15, acknowledged some of the issues that have historically challenged urban communities of color, including drug abuse and domestic violence.

“If we can break those cycles we can do great things for the world,” he said. “Every black community has the potential to be something great.”

The first session of the academy addressed teen dating violence, showing students what an abusive relationship looks like and what rights they should have in a healthy relationship.

“We preach assertive communication,” said peer educator Lei Brutus from the Mayor’s Office to Combat Domestic Violence. “When they know it and practice it a lot then they’ll be able to resolve conflict without getting physical.”

Several participants said they worry about the role social media plays in fueling violent conflicts.

“People have problems over social media and then it escalates out to where violence can happen out in the street,” said Neiman, 16. She said she decided to attend so she can learn what to do if she gets caught up in a violent situation someday.

For others, the stipend of about $20 per day they get for attending the full program was a bigger motivator to attend.

Anderson said he doesn’t expect every teenager who attended last week to understand everything they discussed right away. “Maybe next month, next year, who knows when, it’ll hit them,” he said. That’s when he hopes they will become community leaders for change in their own right.

“I’m part of the anti-violence movement right now because I did the adult academy,” Anderson said. “This trauma class right here changed my whole mind.”

As part of the trauma workshop, facilitator Clifton Hall asked participants to line up on two sides of the room and step into the center whenever he listed something they had experienced. Several stepped forward when he asked if anyone had lost someone they knew to gun violence or knew someone who had been injured in a shooting. Nearly all stepped forward when he asked who lived where they could be stopped by a gang member at any time. After that, he walked them through recognizing and controlling their responses to those situations, and introduced them to available trauma services.

Neiman said these lessons can really make a difference to people her age. “Once you learn this stuff you’ll be more aware of how to fix things and try to help make a better place,” she said.

Derick Latif Scott is the program director for Operation H.O.O.D. (Helping Our Own Develop). Funded by the New York City Council Anti-Gun Violence Initiative, it tackles gun violence as a public health crisis. Scott agreed with Anderson that education and individual actions are the key to changing the mindset of gun violence.

“We can say ‘We all need to [do something]’ but once we say that we’re all looking for the first person to make that step,” said Scott. “So say ‘I need to do something.’”

At least one participant is acting on Scott’s advice. Amirspear, 14, said he’s a musician with a local following. He felt if he attended then many of his peers would follow his lead.

“The youth itself just has so much talent,” he said of Coney Island. “… It’s not just the boardwalk.”