People who are lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and others of minority sexual orientations and gender identities (LGBT+) have a unique and challenging reality. The population has long endured legislative and societal discrimination, health and medical misconceptions, and wide-scale displays of social intolerance. Risk factors such as suicide, substance abuse, isolation, bullying, and truancy are disproportionately prominent among the adolescent LGBT+ population.

People who are lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and others of minority sexual orientations and gender identities (LGBT+) have a unique and challenging reality. The population has long endured legislative and societal discrimination, health and medical misconceptions, and wide-scale displays of social intolerance. Risk factors such as suicide, substance abuse, isolation, bullying, and truancy are disproportionately prominent among the adolescent LGBT+ population.

Adolescents in recent generations are more open with their LGBT+ status than past generations; the average age of coming out is around 16 years old, compared to baby boomers’ average coming-out age of 28. Because LGBT+ adolescents are more vulnerable to harmful risk factors, these youth are in need of increased support from family, friends, schools and communities.

What are GSA’s?

Gay-Straight Alliances (GSAs) fulfill such a need. GSAs are school clubs that provide LGBT+ and allies (heterosexual peers) a safe place in school while providing support, socialization and advocacy opportunities. GSAs are particularly important for LGBT+ adolescents in rural communities because of the typical decrease in population diversity, limited or nonexistent resources for LGBT+ people and a lack of visibility and inclusion in public schools.

In recent years there has been greater social acceptance of LGBT+ individuals, including a demand for their civil rights, leading to the federal legalization of same-sex marriage in 2015 and same-sex adoption in 2016. The increased support, visibility and legal rights for the LGBT+ community may be a reason that more people are now open about their sexual orientation and gender identity, particularly as adolescents. However, there is not increased support, equality, understanding and tolerance everywhere, particularly for LGBT+ adolescents in rural areas.

LGBT+ adolescents are at risk for issues such as truancy, abandonment and homelessness, partially because they often risk losing the support of friends and family when they decide to come out. Without emotional, financial and social support, these adolescents become more susceptible to many of the aforementioned risks. LGBT+ youth who are disowned, bullied and overlooked have needs including shelter, food, clothing, counseling and health-based education.

The rural LGBT+ experience

In rural areas, resources tend to be limited, putting LGBT+ youth at greater risk for problems. A national survey compared the presence of LGBT+-related resources in rural, urban and suburban schools and found that urban and suburban schools noticeably surpassed rural schools with more supportive staff and administration, inclusive curriculum and reading materials, anti-bullying policies, GSAs and supportive community groups.

Additionally, rural schools were more likely to teach abstinence-only curriculum in health and sex education courses than urban or suburban schools. Some rural areas that have a less diverse population have few LGBT+ resources or organizations or visible out LGBT+ community members — this can be detrimental for LGBT+ youth’s identity and healthy development. With limited resources, support and health-based information, it is much more difficult for rural LGBT+ adolescents to thrive and successfully develop.

In order to combat intolerance and provide a supportive space for LGBT+ students, some schools have adopted student-run clubs like GSAs. While GSAs can be found across the U.S., they are particularly important for rural areas. Where there is minimal public LGBT+ presence in a community, LGBT+ youth are more likely to feel isolated as they face instances of misunderstanding and social discrimination. GSAs create a public LGBT+ presence and are inclusive to nonheterosexuals and allied heterosexuals.

GSAs are permitted to exist in public schools through the Equal Access Act, which was created to protect controversial clubs that are often disputed and discriminated against even though the club meets the school’s criteria for student organizations. While GSAs are permissible, resistance in communities and schools when GSAs are formed can be common. Some school boards may be encouraged to change their club criteria so that GSAs will no longer be permitted; others may eradicate all clubs just to be rid of the GSA.

The GSA Tennessee experience

The formation of a GSA at Franklin County High School (FCHS) in Winchester, Tennessee caused such a commotion that many community members and parents urged the school board to try both the aforementioned methods to dismantle the FCHS GSA in 2016. The divide in the community was notable, and residents of Franklin County were still passionate about their positions on the GSA more than a year after the club started. To better understand the experiences of LGBT+ high school students in rural areas and those participating in GSAs, Robin Fair interviewed FCHS GSA supporters and opponents in this rural Tennessee high school.

Social media was used to rally both support and resistance. Both sides were well represented at nearly every school board meeting when the GSA was on the agenda. The permittance of the GSA was debated in school board meetings for nearly three months. The final verdict was that the GSA would remain, but students were required to have a guardian-signed permission form to join any club, and the process to start new clubs was intensified.

Nearly a year after the GSA was founded, community members, former students and parents were interviewed about their perceptions and opinions of the FCHS GSA. Many of the former FCHS students, who graduated before the GSA originated, recalled witnessing bullying and harassment toward males who were perceived as gay or feminine. Those who supported the GSA believed that bullying was worse for LGBT+ adolescents in the area, and that the LGBT+ adolescents and their allies needed a safe space in school.

One person said, “I’m raising a child and I don’t want him to go to that high school at this point … I can’t send him to a school full of hate.” Another commented that the GSA was just as important and had an equal right to exist as religious clubs, explaining that “… if you are going to allow FCA [Fellowship of Christian Athletes], which is going to come in and often give a message that it’s not OK to be gay, you ought to be able to have a club that can say ‘Yes, it is,’ particularly in a place like Franklin County where those students who are LGBT are not likely to get support at home or at their church or wherever. They’ve got to have a safe place.”

Meanwhile, other community members were less enthusiastic about the GSA. They said all students should have the right to feel safe in schools; however, many believed that LGBT+ adolescents were not bullied any more than others, and that heterosexual students were bullied by LGBT+ students for not approving the LGBT+ lifestyle. A parent concluded, “Nobody goes around and just picks out only homosexual people for bullying … Yes, homosexual people do get bullied, but so do overweight people … In fact, if you don’t tell anybody what your sexual preference is, then that would simply not even be a topic of bullying.”

The GSA-opposing parents and community members said the “gay-social agenda” should not be pushed on adolescents or parents. One of the individuals said he was concerned that exposure to nonheterosexuals could turn other children gay in a second-hand manner, proclaiming that the LGBT+ lifestyle was “as harmful as Marlboro Reds [cigarettes]

A universal “No” to Bullying

While there was obvious conflict in the community regarding the GSA, there was one commonality found in all interviews: Bullying was a major problem in FCHS. Robin Fair asked each person how they would increase tolerance between students of differing sexual orientations and gender identities. Among those who supported the GSA, a common idea was to improve sex education policies so that important, health-based information about sex and contraceptives would be available to both heterosexual and nonheterosexual students.

Research shows that abstinence-only policies, like the one in Tennessee, have not been effective in adequately educating youth about sexual health or deterring youth from participating in sexual activities. The abstinence-only policy has withheld vital health-based information from students, many of whom will become sexually active in the near future if they are not already. Studies show that comprehensive sex education is more likely to be effective in reducing teen pregnancy than abstinence-only education.

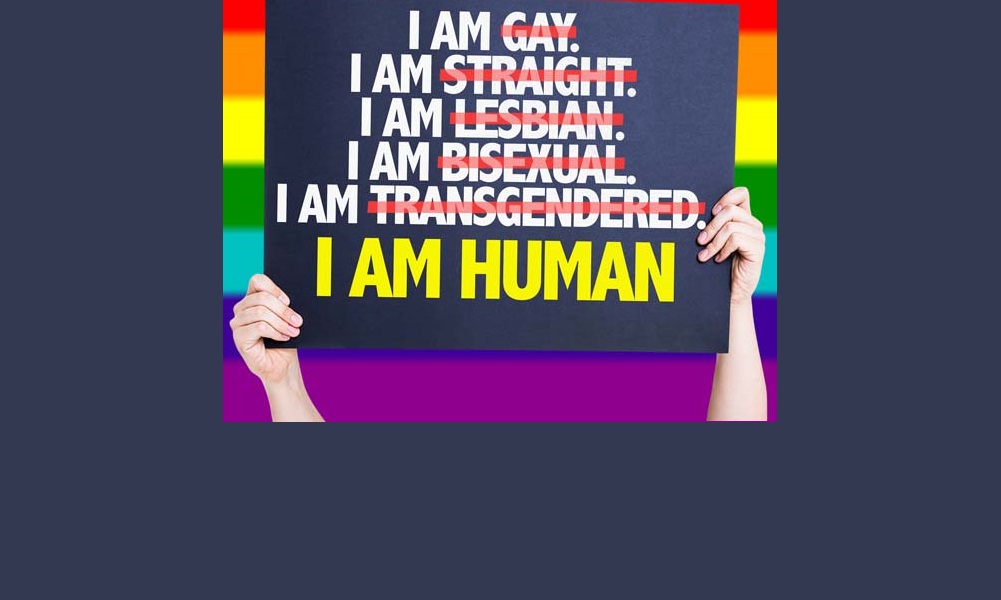

Another idea was to increase awareness of LGBT+ people and issues. Intolerant attitudes are less common around people who have friends, neighbors and family who identify as LGBT+ because personal relationships have the potential to overcome stereotypes and negative perceptions. Positive social change becomes possible when people are able to put a human face to a once-stereotyped label and understand what it would be like to walk in that person’s shoes.

GSA opponents also had ideas about how to addressing bullying at FCHS. A common consensus from opposing interviewees was that the school could benefit from an anti-bullying club, but having an LGBT-focused, anti-bullying club was not an acceptable way to address the issue. An additional idea from these interviews involved enforcing zero tolerance policies related to public displays of affection in schools. However, zero tolerance policies are usually used for offenses like violence and drug possession. Research shows that the severe consequences, such as expulsion and arrest, that come with zero tolerance policies are often not beneficial to the offending students or the school. Alternatives include preventative programs and discipline that appropriately match the severity of each offense.

Solutions

Increasing tolerance between groups of people with differing views and values can be a daunting task, especially when considering factors like religion, societal norms and culture. Inclusive clubs like GSAs can be useful tools in promoting unity, understanding and advocacy. Diversity clubs can help students increase their understanding, awareness and knowledge of different cultures, populations and ways of life. Bullying assessments, such as surveys, can be useful for measuring the level of bullying within a school, and properly enforced anti-bullying policies may encourage students to respect one another and report violations. Finally, educating school faculty and parents about preventing and intervening in bullying situations can help keep everyone safe.

Since LGBT+ adolescents are at higher risk for truancy, substance abuse and suicide, these youth may need more support and guidance, particularly in rural areas that have fewer resources. GSAs may be especially useful for LGBT+ students needing support. Currently, LGBT+ students in Franklin County have a GSA even though a large portion of the community believes it does not belong in their public high school.

Since those interviewed agreed that bullying should be stopped, bullying-prevention and tolerance-promoting interventions could be implemented. FCHS is one example of the many rural communities that need a way for sexual minority students to feel safe and accepted. GSAs, anti-bullying interventions and other methods of promoting peace and acceptance must be considered to improve the well-being and successful development of our country’s youth, regardless of sexual orientation.

Robin Fair is a student at Middle Tennessee State University completing her undergraduate degree in social work. As part of her honors thesis, she researched the struggles and needs of LGBT adolescents in rural areas, community support of and opposition to Gay-Straight Alliances, and modes of promoting tolerance and acceptance between all adolescents.

Justin Bucchio is an assistant professor of social work at Middle Tennessee State University, with expertise in child welfare and LGBT foster youth. Justin’s experience with social work and the child welfare system stems from his early years in foster care, which ignited his passion for serving youth in out-of-home care.

Ariana Postlethwait, MSW, Ph.D., is an associate professor at Middle Tennessee State University’s Department of Social Work. As a self-professed “data geek” committed to social justice, she combines her passions for teaching, research, and conducting community-based research.