Some youth-serving organizations in Mississippi are holding their breaths.

They’re waiting to see whether $14 million dries up.

That’s the amount currently reaching out-of-school programs for kids in high-need, high-poverty communities in the state.

If federal 21st Century Community Learning Centers funding is lost, “there’s going to be a cut in services that will affect kids, families, schools and communities,” said Robert Langford, executive director of Operation Shoestring, which provides intensive after-school and summer programs for 250 children in Jackson.

“We have very good people and culture [in Mississippi] but we are a poor state,” he said.

Aside from the 21st Century funding’s benefit to children, parents depend on the after-school and summer programs to work and to know that their kids are safe, he said.

For the next few months at least, 21st Century has a reprieve.

The federal budget deal hammered out in Congress last week [May 2] preserves funding for the program and actually increases government spending by $25 million.

The vote came less than six weeks after President Donald Trump released a budget proposal that killed the out-of-school time program’s budget entirely.

The president’s March proposal sparked fear nationwide among educators, juvenile justice counselors and others who provide services for lower-income youth and their families. They responded by contacting representatives of both parties who have long supported the program, which for nearly two decades has provided training in the arts and health issues, traditional education and drug counseling, among other services.

In April Langford took eight students to Washington to meet with members of Congress to talk about the program’s benefits. They were among the 30 students in a youth leadership and civic engagement training that Operation Shoestring sponsors with ChildFund International in partnership with Jackson public schools.

Hundreds of national and state organizations that provide services through the 21st Century program sent a letter to leaders of the House and the Senate from both parties, outlining the program’s importance and asking that it be preserved.

The efforts worked even better than many advocates had hoped.

“I thought it was interesting that Congress provided a slight increase, because I thought they might chip away at that a bit,” said John Sciamanna, vice president for policy at the Child Welfare League of America. “Certainly there have been a lot of signals that Republicans don’t like a lot of things that were said [in the president’s budget proposal] about 21st Century Learning, and this shows there is something to that.”

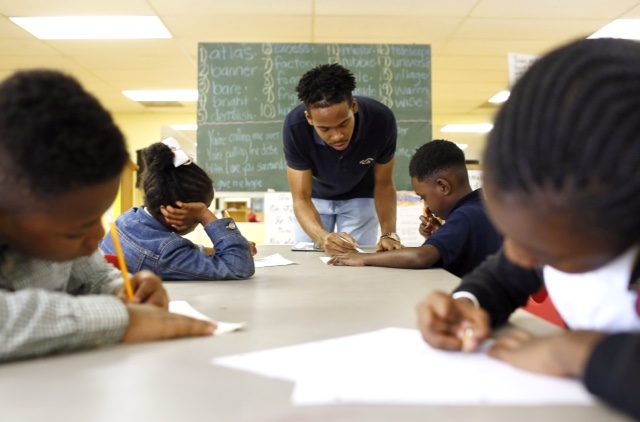

Barachiel Beasley, right, leads a class at Operation Shoestring, an after-school program, in Jackson Thursday.

While last week’s budget compromise saved the program until at least Sept. 30, there is no guarantee after that. Trump has suggested that a government shutdown in support of his budget priorities may be a “good” solution to the country’s budget battles.

Sciamanna said he expects the president will submit a complete, line-item budget sometime in the next few weeks. Trump, who used his Twitter account to criticize the budget compromise, could again call for the program to be abolished.

But for now, 21st Century’s national budget will jump to $1.19 billion for fiscal year 2017, and serve about 1.6 million families, according to a review of the pending budget and a 2016 analysis by the Afterschool Alliance.

In his March budget proposal, Trump and his budget director, Mick Mulvaney, argued that the program had been ineffective. That assertion was contradicted by providers, families, members of Congress and a detailed 2016 study by the Charles Stewart Mott Foundation.

Supporters of 21st Century and service providers said federal funding is crucial to making after-school programs work, and cannot be replaced by foundations. Complicating matters is the fact that programs serving the elderly, food and nutrition programs and other services for the poor or those with health needs also face steep cuts.

Tamu Green, founder of the nonprofit after-school program SR1 in Ridgeland [Mississippi], said after-school programs could experience a double whammy, since the president has proposed cutting the AmeriCorps program. SRI has had 64 AmeriCorps volunteers, he said, and many after-school programs rely on them.

State and local governments will be asked to fill part of the funding void, but many don’t have the money needed.

“We are nowhere near meeting the demand for after-school opportunities now, so if the worst happens, and the funding isn’t renewed, there is no way to replace that,” said Ellie Mitchell, executive director of Maryland Out of School Time, in a recent interview. “If you name a public service — whether it is feeding people, dealing with the elderly or whatever — so many are on the chopping block it takes your breath away.

“There is no way that local tax dollars or private foundations will ever be able to fill that need,” Mitchell said.

Langford said that Operation Shoestring is working with a lot of service organizations, philanthropists and agencies such as the state Department of Human Services to preserve funding.

“Our philanthropists have very limited resources,” Langford said.

“We don’t know what’s going to happen starting Oct. 1,” he said.