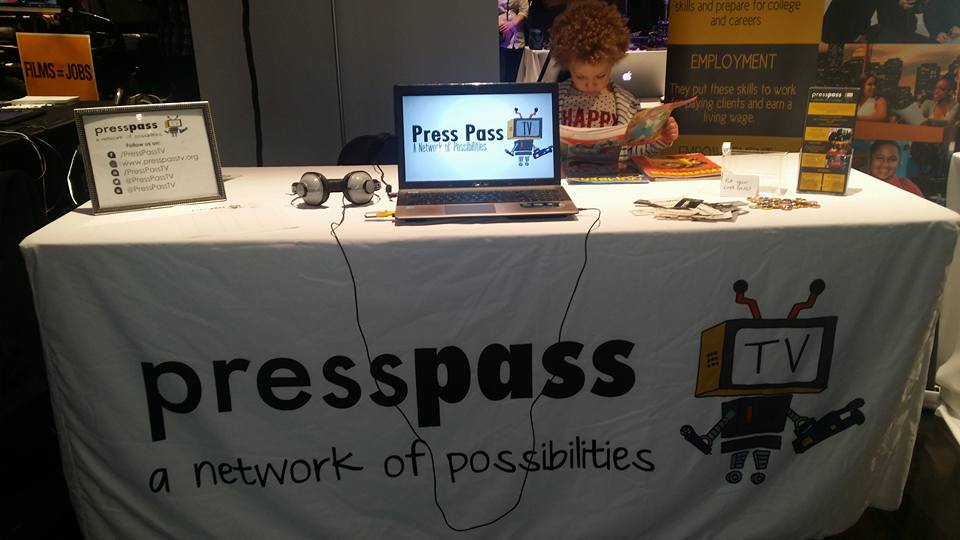

Press Pass TV

At Press Pass TV, a youth organization in Boston, teenagers learn to analyze news media while learning photography, video production and animation. In January, Press Pass TV will change its name to the Transformative Culture Project.

Judging the credibility of news has become a big issue the past few months: So say many educators, journalists and others on the heels of an election in which fake news sites flourished, a gunman threatened restaurant patrons based on false news and the president-elect made unsubstantiated claims on Twitter.

“[Media literacy] is essential in this current environment when you have so many people who absolutely reject credible sources of information and believe anything they see on the internet,” said Erin McNeill, founder and president of the three-year-old nonprofit, Media Literacy Now.

“It’s more than urgent,” she said.

But a campaign to require media literacy in schools throughout the United States has a long way to go. Only Minnesota has added the subject to state Common Core standards. Washington state mandated last March that state education officials develop a plan to teach media literacy in all schools. Some other states are also integrating it, according to Media Literacy Now.

However, most kids don’t get media education in school, McNeill said. “There’s a great role for out-of-school (OST) time to play here,” she said.

Some OST organizations are already teaching kids to analyze and make their own media. Resources and curricula are available for others.

What’s media literacy?

Media literacy is the ability to think critically about media messages as well as to create messages using media, according to Media Literacy Now.

“You need to analyze and evaluate the messages and also create your own messages,” McNeill said.

Young people don’t have adequate knowledge to do, however. In November, a report from the Stanford University School of Education showed middle school students have a difficult time distinguishing ads from news articles, and high school students and college students are easily duped by false information.

Press Pass TV

At Press Pass TV, a youth organization in Boston, teenagers learn to analyze news media while learning photography, video production and animation. In January, Press Pass TV will change its name to the Transformative Culture Project.

Last year, a University of Connecticut researcher reported that middle school students are poor at judging the credibility of online science information.

Kids need to know how to create their own filters, said Cara Berg Powers, executive director of Press Pass TV, a Boston nonprofit that trains low-income youth in digital media and video production.

“There is nothing more important than people’s ability to discern what is coming at them constantly,” she said. If kids aren’t taught this, it’s the equivalent of saying they “don’t deserve self-determination,” she said.

Powers said five key questions are important in analyzing media adequately. These questions were developed by the Center for Media Literacy, a nonprofit founded by a former high school English teacher who has become a proponent of media literacy.

- Who created the media message?

- What creative techniques were used to get attention?

- How might various people experience this message?

- Which values and points of view are represented by or left out of the message?

- What is the purpose of the message?

Powers said Press Pass TV offers after-school and summer programs in Boston and nearby Worcester and Holyoke.

Media literacy skills are a core part of the program, which serves about 150 kids per year, said Program Manager Reggie Williams. Kids learn photography, video and basic animation.

The program also functions as a creative agency, providing video and photography services to nonprofits, corporate clients and small businesses. Youth producers work on these projects and in the process gain valuable skills.

Other media-making youth organizations exist in a number of cities. Among them are Youth Radio, based in Oakland, California; VOX Teen Communications in Atlanta; Free Spirit Media in Chicago; and Portland Community Media in Portland, Oregon.

Providing curricula and programs

OST organizations also provide media education to youth along with simpler hands-on projects.

The nonprofit News Literacy Project, founded in 2008, collaborates with teachers and journalists in school classrooms and after-school programs in New York City, Chicago, Houston and Washington, District of Columbia.

Peter Adams, senior vice president for educational programs at the News Literacy Project, said the organization had served 25,000 students in the past eight years.

The after-school program runs eight to 10 weeks, and includes introductory news lessons and a collaborative student project. Among other things, it teaches young people learn how to tell the difference between verified information and “spin,” opinion and propaganda.

The organization plans to expand to Los Angeles, Adams said.

The News Literacy Project also has a free online curriculum known as Checkology which is available to schools and OST programs nationally. Adams said 700 teachers and 64,000 students have registered to use it.

Adams said news literacy is important because “the health of the democracy depends on citizens’ ability to discern credible information.”

What kids learn

The National Association for Media Literacy Education is an organization of educators and others dedicated to expanding media education.

According to NAMLE, media literacy skills can help youth:

- Develop critical thinking skills.

- Understand how media messages shape our culture and society.

- Identify target marketing strategies.

- Recognize what the media maker wants us to believe or do.

- Name the techniques of persuasion used.

- Recognize bias, spin, misinformation, and lies.

- Discover the parts of the story that are not being told.

- Evaluate media messages based on our own experiences, skills, beliefs, and values.

- Create and distribute our own media messages.

- Advocate for a changed media system.

McNeill of Media Literacy Now said hands-on lessons are very attractive to kids in after-school programs. Kids are excited at the chance to use digital tools to do things such as making YouTube videos and posting on social media, she said.

“It’s a great way to engage kids in after-school programs,” she said.