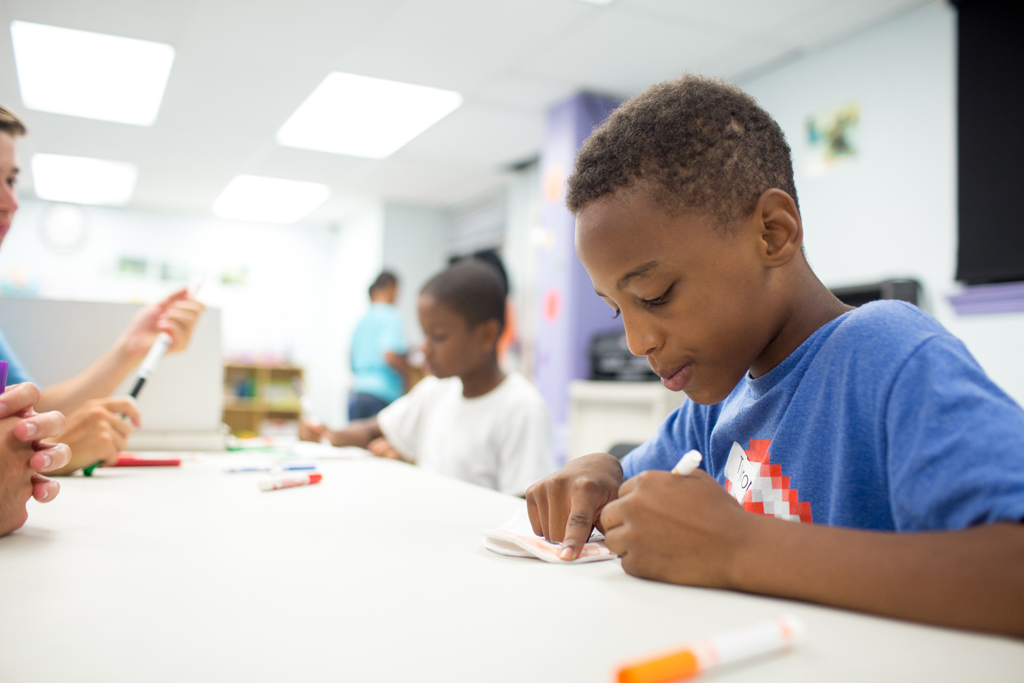

photo by Mayline Yu Photography

Little Lights Urban Ministries in Washington, District of Columbia, uses storytelling to help raise money for and attract volunteers to their after-school, arts, economic empowerment and jobs training programs.

At Little Lights Urban Ministries in Washington, District of Columbia, stories are part of the organization’s culture.

Staff members who work with youth, families and communities in poverty regularly take time to write down inspiring moments in the lives of the clients they serve in after-school, arts, economic empowerment and jobs training programs. In as much as detail as they can, the staff members try to capture what life was like for their clients before arriving at Little Lights and how and why it’s changing.

A few times each year, the organizations ask volunteers to do the same, to highlight what has made their experience worthwhile.

They call them GEM Stories — genuinely exciting moments — and they go into a file that communications and development staff members can consult when they’re crafting a direct mail appeal, a newsletter, a video or other materials. The materials are the foundation to delve deeper into clients’ stories, with their consent and participation, later.

The detailed stories make a difference by going beyond data or too brief, one-dimensional stories to engage audience’s emotions, said Amy Leonard, Little Lights’ development and communications director.

She remembers a banquet audience’s reaction after the group showed a video following one woman’s journey with the organization. “That was what people were talking about when we left: ‘Who’s Crystal? How do we help her? She’s amazing,’” Leonard said.

Another success came when an anniversary book Little Lights designed inspired a major donation after a supporter passed it along to a friend who was deeply moved by the stories it included.

“We’ve realized that stories are what people take away,” Leonard said.

Little Lights isn’t alone in finding ways to make stories an integral part of how they fundraise, encourage volunteerism or persuade people to engage in a cause by writing to their legislators or signing a petition.

John Trybus, director of the Center for Social Impact Communication at Georgetown University, said storytelling is having a moment in the nonprofit sector as organizations seek to cut through the noise of the busy media landscape to get their message heard.

“Stories unite people. They’re the currency of life because they help make sense of complexities,” he said.

More individual donors

A few years ago, the center and the Meyer Foundation, a grant-making organization in the greater Washington, D.C., region, teamed up to produce “Stories Worth Telling,” a research project that explored how nonprofits were using stories and what they could do better.

The project was inspired by the foundation’s desire to make sure its grantees are financially sustainable, said Rick Moyers, the foundation’s vice president for programs and communications. In particular, they wanted to know how groups could boost their income from individual donors, which makes up the majority of private donations to nonprofits in the U.S., according to the National Center for Charitable Statistics.

Some nonprofits have become so adept at targeting corporations and foundations with data, they forget the value of an appeal to the people in their communities, Moyers said.

“Individual donors tend to give based on emotion rather than outcomes and data,” he said.

For the project, Georgetown researchers highlighted how to make a story compelling and when to put stories to use.

Trybus said an important first step is to build an organization’s culture of storytelling by engaging staff and volunteers to share their own stories as well as those of clients, similar to the way Little Lights has done. Even hearing how a fellow staff member found their way to a mission-oriented organization can inspire an appreciation for stories, and this kind of story cultivation and sharing is something even small organizations without a lot of resources can undertake.

“There are still a lot of organizations that don’t have the mindset that stories can inspire action,” he said.

Trybus said nonprofits also should think carefully about how to dedicate their resources by asking questions such as “Why should a particular fundraising effort rely on storytelling?” and “Who’s the best person to tell this story?”

Small nonprofits may need to outsource their storytelling, especially for more technical productions such as videos or podcasts, but Moyers said a growing number of pro bono resources and the rise of easy-to-use and less expensive equipment should make it somewhat easier to keep projects in house.

“If you know what you’re doing, you can take high-quality photos on your iPhone, you can edit videos on your phone,” he said.

Making content compelling

The “Stories Worth Telling” researchers came up with five main criteria for a story. Stories should feature a central character and detail an experience, journey or transformation with a strong, early hook that tells the audience why they should care. They also should strive for authenticity by including rich details and featuring the character’s own voice, and aim to evoke emotions that will cause an audience to act.

In an analysis of nonprofit materials, the researchers found that only 54 percent of content identified as a story actually met those criteria. The others fell into categories such as event recaps, testimonials or profiles.

Trybus said one critical underlying principle in any story is to be sure the storyteller’s voice and life experiences shine through. The narrative doesn’t have to be perfect; in fact it’s better if it allows for life’s messiness because it rings true, he said.

At Little Light, Leonard said it can be tricky to ask about a tough time in someone’s life to get the details that will make a story authentic, but she’s found people are eager to share when asked in a thoughtful way.

“It’s always a delicate balance to know how far to delve into the before, into the gritty, messy details of someone’s story. But if you can do that sensitively, it can have a greater impact than painting a fluffy story that only looks at the after,” she said.

Leonard does try to end on a hopeful note, though. It’s a crucial turn, one she thinks motivates donations out of excitement for the potential of clients and programs, rather than a sense of obligation. She looks for a way to showcase a solution that’s working for a client, without suggesting that everything is now perfect in their life.

“For us and I think a lot of nonprofits, we don’t only want to be about the problem,” she said.