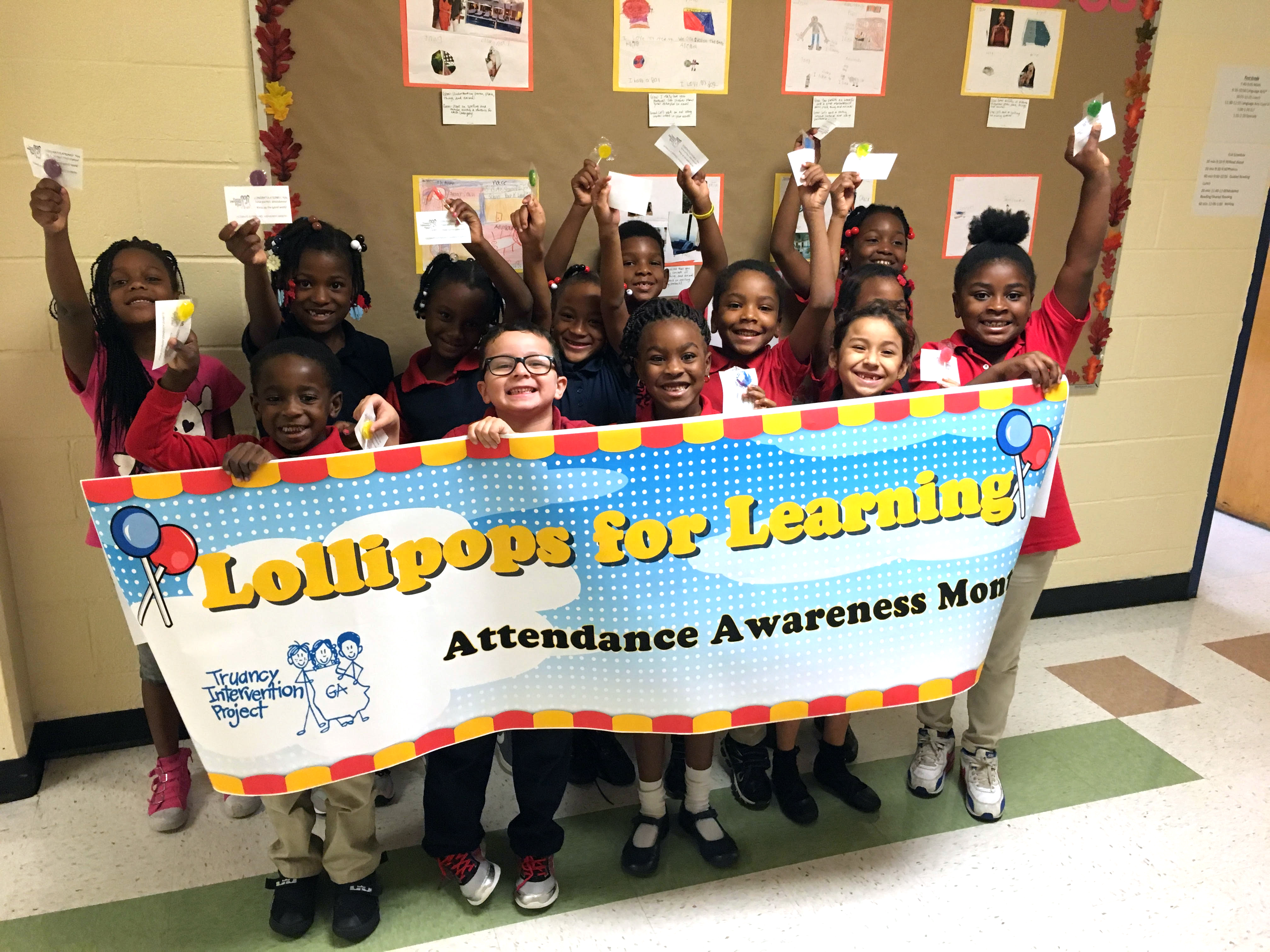

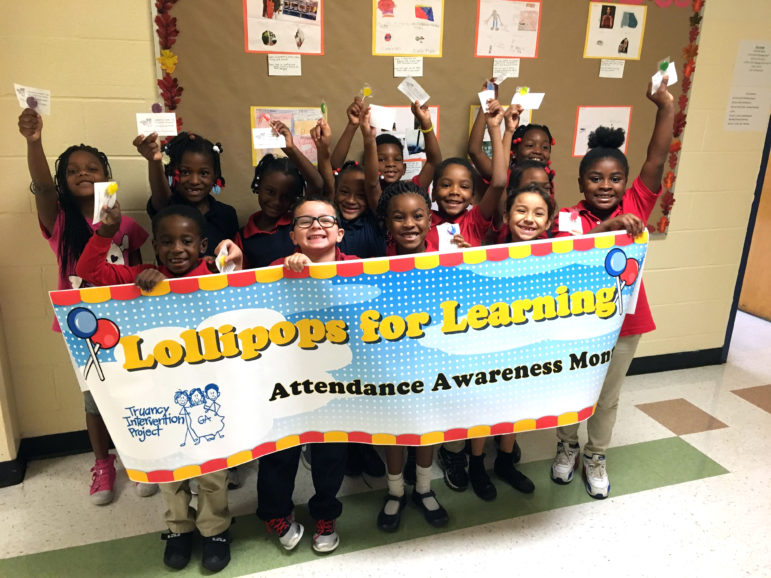

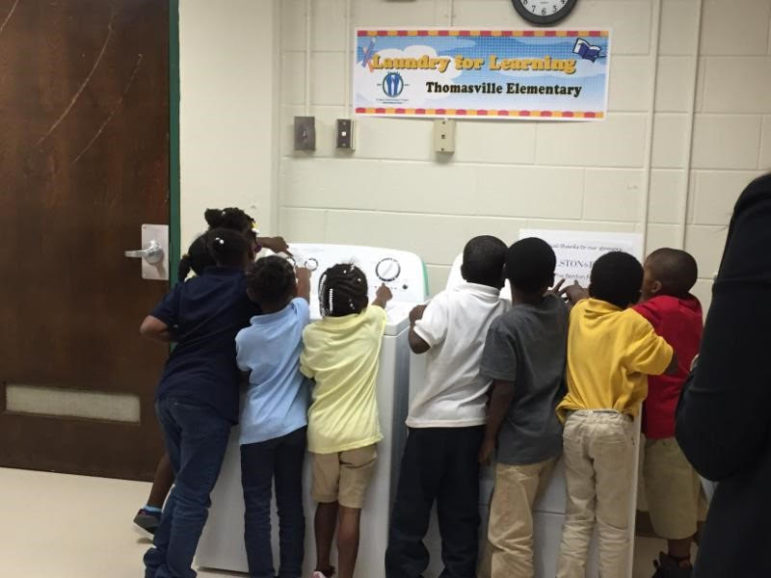

Photos courtesy of the Truancy Intervention Project

.

Jessica Pennington has seen a lot of students who are frequently absent from school. As executive director of the Truancy Intervention Project in Atlanta, she pairs kids who have high absences with volunteer mentors who help address the problem. The organization’s goal is to keep students in school so that they can be successful there.

Pennington was pleased to hear that the high school graduation rate in the United States has risen to 83.2 percent, based on a White House announcement earlier this week. It’s the fourth year in a row the national rate has increased.

However, she said, “the numbers are small and we still have plenty more to do.”

Chip Carter is marketing director for Communities in Schools of Nevada, which is also focused on children’s success in school. It places a site coordinator in each of 59 schools in three Nevada counties to monitor the needs of 58,000 students and provide services to them.

“We provide a caring adult who helps with the barriers a student may face,” Carter said. But the organization can serve only a fraction of the schools that need it, he said.

Both Georgia and Nevada are states that have raised their high school graduation rates more than 10 percentage points since 2011. But both rank still very low in comparison with other states. Georgia’s rate is 78.8 percent (40th) and Nevada’s is 71.3 percent (47th).

In a speech Monday, President Obama pointed to nationwide success in improving graduation rates. He credited federal investments in early education and Race to the Top funding, which encourages states to raise standards.

GradNation, a national dropout prevention campaign, said in a statement that the focus on graduation rates by the last two presidents and by state governors has paid off.

In 2008, states were required to use a standard calculation of graduation rates and in 2011 were required to intervene in schools with low graduation rates, This had a major impact, according to GradNation.

It said states and districts are working to increase teacher quality, use data in decision-making and raise expectations for students. Equally important, according to GradNation, is involving caring adults, combating chronic absenteeism and noticing early warning signs.

“It’s been a real collaborative effort,” Pennington said.

The Truancy Intervention Project served 425 kids last year, she said. It was founded in 1991 and has worked with about 10,000 students since then in Atlanta Public Schools and Fulton County Schools. Its early intervention program puts trained volunteers with children in 20 elementary schools that have a high number of absences. Its high school program pairs volunteers with youth who have been deemed truant by a court.

Eighty-eight percent of the kids improve their attendance, she said, although the percentage is lower among the older students.

Communities in Schools of Nevada is an affiliate of the national nonprofit Communities in Schools. The organization puts site coordinators in schools to serve as mentors and connect kids with needed resources from food banks to eye exams to housing.

“Site coordinators form strong relationships with students and their families,” Carter said. They sometimes act as a third parent, he said.

The risk of dropping out is usually related to poverty, he said. There are stresses on the family, kids may be living with people other than their parents and the expectation around education may be lower.

“A lot of it just comes down to poverty,” Carter said.

Eighty-seven percent of the high school seniors who get assistance from the site coordinator go on to graduate, he said, much higher than Nevada’s overall graduation rate.

“While we are pleased to see continued progress in raising graduation rates, we realize that much work remains,” GradNation said in a statement.