Fines and fees imposed in juvenile court can drive youth deeper into the system and their families deeper into poverty, a new report says.

Every state imposes monetary penalties or costs on juveniles, a burden that hits families who are already struggling especially hard, both emotionally and financially, according to the report by the Juvenile Law Center of Philadelphia.

The costs can include fees to attend programs that are alternatives to incarceration or to have a mental health evaluation, charges for record expungement and restitution payments to victims.

When families can’t pay, the consequences may include sending a youth to a juvenile placement rather than an alternative community-based program, keeping a youth on probation longer than they otherwise would be or having their driver’s license revoked.

“This is a glaring example of justice by income,” said Jessica Feierman, associate director at the center and the report’s lead author.

The financial burdens of adult court have drawn increasing attention in recent years, but the juvenile system has gone largely unexamined, prompting the center’s researchers to wonder about the experiences of young people and their families. For the report, they examined state statutes and surveyed families and practitioners in most states.

“We got a resounding answer that young people all across the country are facing court debt. It’s harming them and their families,” Feierman said.

In a companion report, criminologists also zeroed in on how costs or fees affected recidivism in Allegheny County, Pennsylvania.

The study, one of the first to look at the connection, found that financial penalties increased recidivism instead of deterring further offenses.

In addition, the report found a link between court-ordered financial obligations and racial disparities. Youth of color were more likely to still owe money after their cases were over, leading to further charges, longer probation or other punishments.

Feierman said the findings point to one way to curb racial and ethnic disparities in the juvenile justice system — by moving away from fines and fees that disproportionately affect some communities.

State experiences

Gary Blume, a partner at Blume & Blume Law in Alabama, said he often sees families struggling with the financial problems the report highlights. One common scenario is that a juvenile on probation is hit with a fee that they can’t pay and has to remain on probation until they can.

During that time, they can be sucked further into the system because of curfew violations or other technical violations — which often comes with a new round of costs.

“It just creates a vicious cycle,” he said.

The consequences also aren’t uniform, Blume added. While some judges are mindful of the burdens families face, others are less so. And even when judges would like to waive fees or fines, some costs are mandatory.

Feierman said some of the fines and fees are set up as a punishment or a way to right a wrong, such as restitution payments. Others are a funding mechanism, a way to fill gaps in juvenile justice budgets that have been slashed.

All of them can be overwhelming to a family, even in small amounts, said lawyers and advocates across the country. And there are hidden costs, too.

A family may need to find the money for a class that’s an alternative to formal prosecution, but they’ll also need to come up with the money for transportation, said Mae C. Quinn, director of the Roderick and Solange MacArthur Justice Center at St. Louis.

“The cost of just doing business needs to be taken into account as well,” she said.

One fee that differs somewhat from the others are restitution payments that go directly to victims, Feierman said. Helping to make a victim whole may make sense, but even then, states should be aware of how much money juveniles and their families have and whether alternatives such as community service may be more fruitful.

“If a young person doesn’t have the money, it’s not going to help the victim and it’s not going to help the young person get back on track,” she said.

Financial obligations vary

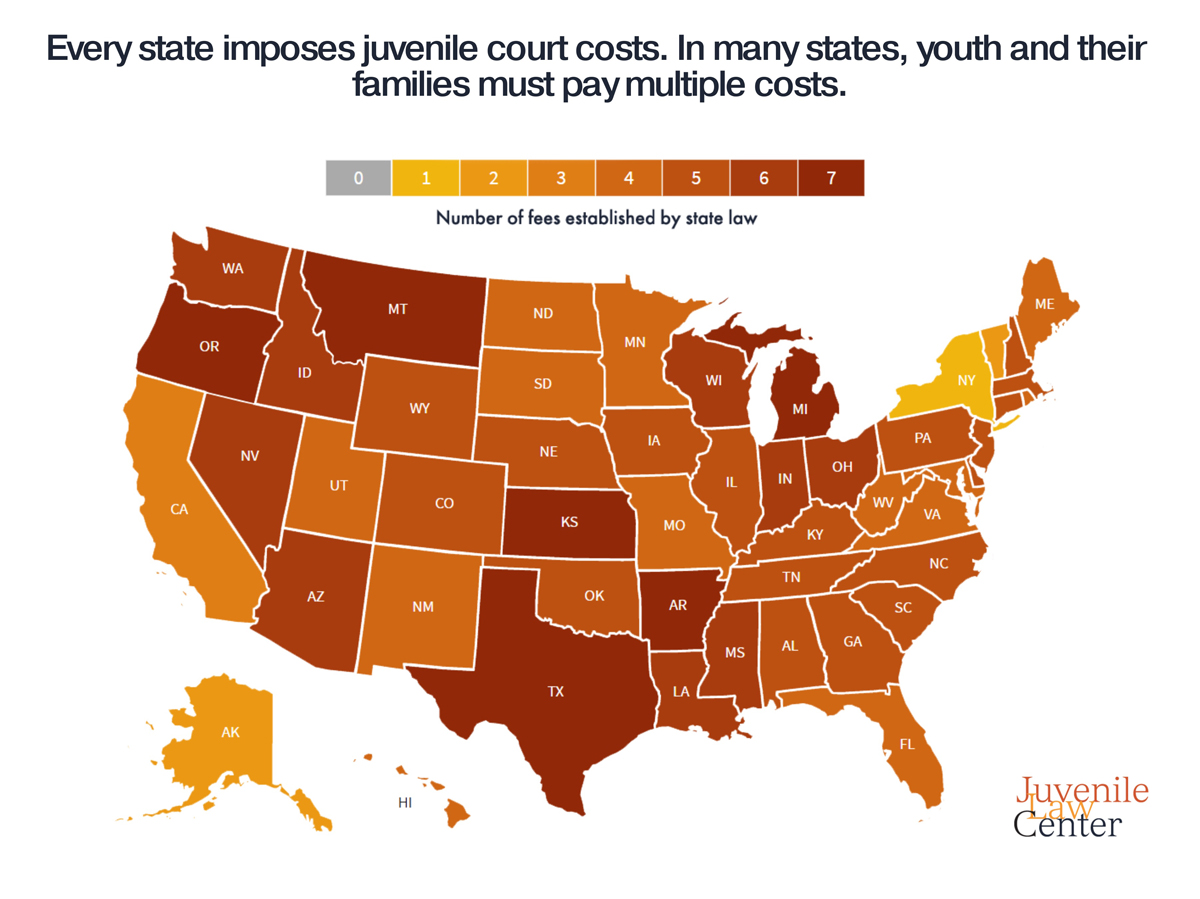

The report looks at eight categories of financial obligations that states use: probation or supervision, informal adjustment or diversion, evaluation and testing, cost of care, court costs and fees, fines, expungement and sealing, and restitution.

All states impose restitution costs of some kind, but they vary in their use of costs across the other categories. Under state law, New York only uses restitution fees; Alaska and Vermont use restitution and cost of care fees. Others though, including Texas, Arkansas, Oregon, Kansas and Michigan, have fees or fines that fall into seven of the categories.

Most states and localities haven’t made any major moves to change their practices, but some examples exist, according to the report. In Alameda County, California, officials put a moratorium on fees and costs after a report showed the harm to families and a minimal financial benefit to the county. And Washington state lawmakers eliminated a variety of fees, allowed youth to petition the court for relief and gave judges discretion to consider a juvenile’s ability to pay restitution.

“Counties and states across the country should consider a similar approach — eliminating harmful costs, fines, and fees, and ensuring that any orders of restitution are reasonable and effectively balance the victim’s need to be made whole with the financial reality of youth and their families,” the report said.

Matt Conklin, a juvenile justice reform advocate at Kansas Appleseed, said he was struck by how many fines and fees Kansas applies. The group will be encouraging families to tell their stories and sharing the information with legislators to encourage reforms, he said.

“This is the signal for us, the wake-up call that can hopefully inspire us,” he said.

This story has been updated.