Badlands in the northern portion of Pine Ridge Indian Reservation. More than 100 young people on the reservation attempted suicide in four months in 2015.

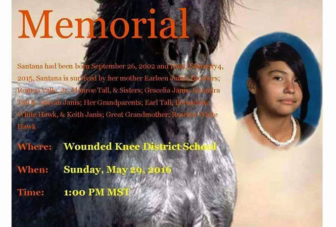

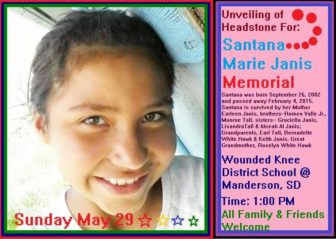

On May 29, family, friends and community members gathered at the Wounded Knee District School in Manderson, South Dakota, to unveil a headstone for Santana Marie Janis.

She died a little more than a year ago, one in a string of suicides among young people on the Pine Ridge Reservation. She was only 12 years old.

Pine Ridge, home of the Oglala Sioux Tribe, drew national attention last year after nine young people aged 12 to 22 killed themselves during a four-month period. Another 103 youth attempted suicide in that period, according to the New York Times.

Santana House

Santana Marie Janis, who died by suicide last year at age 12, was remembered recently in a memorial service as part of an ongoing effort to prevent additional suicides among Native American youth in South Dakota.

Suicide is the second-leading cause of death, behind unintentional injuries, for American Indian youth ages 15 to 25, Robert G. McSwain, acting director of the Indian Health Service told Congress last year. The suicide rate for this age group is four times higher than the national average, he said.

Figures released in April by the National Center for Health Statistics show the suicide rate for Native American females of all ages grew 89 percent from 1999 to 2014, the largest increase for any group.

Suicide is “a form of expression of the despair and hopelessness experienced by some Native youth,” McSwain said.

Pine Ridge Reservation has one of the highest poverty rates in the nation, along with high rates of alcoholism and drug use. Few jobs are available there, and medical care is inadequate, according to the American Indian Relief Council.

[Related: Screening Youth for Depression Saves Lives]

Santana’s grandfather, Keith Janis, said the young people on Pine Ridge are growing up in an area where “there’s a huge amount of racism” against Native people. He described one incident in which his granddaughter and a group of young people were in a hotel in Rapid City, South Dakota, and heard a white woman call them “filthy Indians.”

“But it’s not just one thing,” he said. He points to the poverty, lack of jobs and homelessness. He said other people were benefiting economically from the lands that were taken from the tribe, while the tribe does not.

Since Santana’s death, Janis has taken part in a suicide prevention project through Facebook called Santana House. In addition to an online gathering place, the site offers adults and youth a place to confidentially share concerns about kids who may be depressed or having problems.

Janis and the other adults involved in the site can reach out to them and, in some cases, connect them with mental health professionals.

“All the kids are on social media,” he said. “There’s a lot we can do.”

In 1890, Wounded Knee was the site of a massacre of 300 Indians by U.S. troops. In the following years, many Native youth were taken from their families, put in boarding schools and forced to give up their culture.

Ruby Gibson, founder of a South Dakota nonprofit counseling center Freedom Lodge, talks about youth suicides in terms of historical trauma.

“If there are repeated traumas — assaults, deaths, loss of homelands — all the things we know happened to Native people, if all those things are happening continuously or simultaneously, then there’s never any chance to recover,” Gibson told the Rapid City [South Dakota] Journal.

Through Freedom Lodge, Gibson offers trainings to educators at South Dakota schools about suicide, the stress that kids feel and its relation to historical trauma.

More related articles:

What Three People Learned About Suicide and Kids

Teen Suicide May Be “Contagious,” Says Canadian Study

At Thanksgiving, Reflecting on Justice for Native Americans