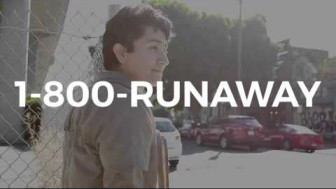

WASHINGTON — “I really didn’t feel safe anymore at home,” says the first young person in a new public service announcement campaign that aims to connect runaway and homeless youth with the support they need.

“Sometimes I wouldn’t eat — it was like this hunger pang in your stomach,” says the next.

“It was just so lonely,” says a third, who holds a sign that reads, “I became homeless for being gay.”

The new campaign allows teenagers and young adults to explain their experiences of homelessness — and of finding support — in their own words and offers the National Runaway Safeline as a resource to those seeking help.

The federal PSA campaign launches this month, alongside the release of a study that looks at the varied experiences of homeless youth ages 14-21 in 11 cities.

The study found that more than half the homeless youth became homeless the first time because they were asked to leave by a parent or a caregiver. On average, youth had been homeless for 23 months. Only 29.5 percent reported they had the option to return home.

“An important step toward ending youth homelessness is getting better data and getting a better understanding about why young people become homeless, what happens to them when they are homeless and what services they need,” said Mark Greenberg, acting assistant secretary at the federal Administration for Children and Families, a division of the Health and Human Services Department.

The study, conducted by researchers at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln, is based on interviews and focus groups with nearly 900 homeless youth in cities with a federal-funded Street Outreach Program. The participants included young people seeking services from the programs as well as others who were not.

Mary Fraser Meints, executive director of Youth Emergency Services in Omaha, Nebraska, a Street Outreach Program site that participated in the study, said she was shocked by the length of time youth reported being homeless.

“Think of somebody 15 homeless for two years. Developmentally, they’re at a formative stage. Educationally, that’s affects their whole lives,” if they’re not completing school and working toward college or a career, she said.

[Related: Kids Mostly Homeless Due to Poverty, Global Study Finds]

The data already has helped the group focus on important services for youth, such as a need for shelter for teenagers who weren’t eligible to stay in youth shelters funded by certain federal grants because they were older than 18, but couldn’t seek a bed in an adult shelter because the age of majority in Nebraska is 19.

“We use the data to identify service gaps and fill them or to work with others to fill the gaps,” Fraser Meints said.

The study also found:

- About half the participants had experienced foster care. Those with a foster care history had been homeless for an average of 27.5 months, compared with 19.3 months for their peers.

- Twenty percent of the youth identified as bisexual, 10 percent as gay or lesbian and 6.8 percent as transgender. The percentage of transgender youth was three times higher than a recent national estimate of transgender youth, which the researchers said could reflect the inclusion of several major cities that have providers who are more accepting of transgender youth or provide more culturally appropriate services.

LGBT youth and former foster youth reported higher levels of victimization — including sexual assaults and rape, physical assault with or without a weapon and robbery — before and after becoming homeless compared with other youth in the study. LGBT youth also were more likely to report trading sex for food, money, shelter, drugs or protection than their heterosexual peers.

The researchers cautioned that their findings aren’t nationally representative but said the diversity of experiences reported by homeless youth show the importance of having an array of tailored services to support them.

And because there is not a coordinated system of care for homeless youth, the study’s authors stressed the importance of working together across systems.

“Bringing together stakeholders from all parts of the youth-serving community can help build the needed continuum of care — prevention, early intervention, longer-term services, and aftercare — for homeless youth,” they wrote.

When the participants were asked about their current needs, 71.3 percent said they would like help training for or finding a job. More than 50 percent also said they needed help with transportation, clothing, a safe place to stay, education, access to laundry, a place to be during the day and a phone.

Rafael López, commissioner of the Administration on Children, Youth and Families at ACF, said the data paints a fuller portrait of the experiences of homeless youth, one that encourages empathy and better policy responses.

He said there’s often one vision of youth homelessness — the teenager sleeping on the street or under the bridge — while there’s actually a range of experiences.

“We have to be more thoughtful about the way we talk about our young people,” he said.

López also said policymakers and service providers need to think about what’s happening in a family that makes running away the best option for a young person, whether they choose to do so or are asked to leave.

He said the high rates of former foster care involvement among homeless youth point to the need to think about how child welfare interacts with other systems.

“How do we break down these pipelines, that go from a child born with their own extraordinary talents to a young adult living on the streets?” he said.

The fact that 14 percent of homeless youth reported caring for a child and 9 percent were pregnant also points to the need to consider how children and youth move through the systems designed to help them, López said.

More related articles:

Counting the Homeless Kids in Atlanta

Low-Income, Homeless Teens Use Art for Job-Readiness

Advocates Say Homeless Student Numbers Point to Need for New Definitions

TANF Helps Support Homeless Families