Real Boy

Bennett Wallace dressing.

“Mama, I’m sorry / I didn’t mean to make you cry

“I’ve been trying to say hello / You thought I was saying goodbye.”

Those lyrics by California singer-songwriter Bennett Wallace are at the heart of “Real Boy,” an upcoming documentary that follows a transgender teen finding his way in a new world while trying to preserve the family ties his transition has strained. Wallace finds solace in his music and in his friendship with Joe Stevens, a fellow musician and transgender man who becomes his mentor.

“This is a film about what it feels like to just want to be loved by the people you’re closest to, and how powerful that feeling is, and how painful it is when there’s something that gets in the way of it,” said Shaleece Haas, the film’s director-producer.

The film underwent a transition of its own during the 3½ years Haas followed Wallace, she said.

“I met Bennett and Joe on that first day and really thought this was going to be a buddy movie about the two of them,” Haas said. “And it wasn’t until I met Bennett’s mom, Suzy, that I realized there was a really deep core of this story that was really about family — about given family as well as chosen family.”

Real Boy

Singer/songwriter Bennett plays for his mother.

The family’s home videos capture Bennett’s earlier life as Rachael, a precocious, creative girl who grows up as “a boy with the wrong body parts,” as he puts it. As the film begins, he’s had therapy and started hormone treatments, throwing him into a kind of second puberty. He copes with the help of his friend Dylan, who is making the same transition, and Stevens, who went through the same process about a decade earlier.

Wallace has overcome problems with drug addiction and cutting himself before the film starts — and in the process, he discovered other people struggling with the same gender-identity issues via YouTube, where many posted videos recounting their stories. He realized what he needed was to make a transition himself.

“The greatest gift I received while browsing was that I knew I wasn’t alone,” he said.

Wallace met Haas when he was opening for Stevens at a show in Sacramento, California, by transgender musicians in early 2012. The then-19-year-old Wallace had just come out to his family a couple of months before and hadn’t started his physical transition yet.

“I was so delighted by him,” Haas said. “He was really starstruck by Joe; he was awestruck by all of the people around him.

“His music was really striking. His lyrics were really great. But he was also really clearly kind of on the cusp of that moment of kind of growing up,” Haas said. “I was also really moved by the relationship between Bennett and Joe. The beginning of that mentorship relationship were already there, even though they had really just met.”

Wallace and Stevens met at a sober youth conference and hit it off as fellow musicians. In addition to music and their transitions, both struggled with addiction.

“We’re so similar in that we had a really rough time,” Stevens says during the film, adding, “If I can make it any easier for him, it’s worth going through all of that.”

“Real Boy” bows at the Independent Film Festival Boston on April 30. It also has been accepted for eventual broadcast on PBS.

The film comes out at a time when transgender issues have broken into pop culture, with TV dramas like “Transparent” winning top-shelf awards and celebrities like Caitlyn Jenner making headlines.

[Related: Runaway and Cast Off: One LGBT Teen’s Story]

Haas said she’s delighted young people “are having conversations about gender that are blowing everyone’s mind.”

“That to me is so liberating and awesome,” she said. “And I know for a lot of people, it’s still the weirdest thing they’ve ever heard of, but I think it’s great.”

Real Boy

Bennett Wallace (left) shows Joe Stevens how his chin hair is coming in.

But behind the headlines, transgender men and women still struggle with some of the basics of everyday life — like staying alive or holding a job.

“We are still seeing one of the highest rates of violence and murder of trans women of color that we have ever seen,” said Haas, a lesbian who’s done volunteer work for LGBTQ organizations in the San Francisco area. “People are still dying. People are still being fired from jobs.”

Society needs to make sure that the rights of all people are protected, she said, “even the people who look different, even the people who do sex work, even the people who aren’t on the cover of magazines.”

As a middle-class white kid, Wallace’s life “is very different” from many other transgender people, said Haas. “That said, for trans youth like Bennett and many others, the rates of suicide are incredibly high. The rates of depression and substance abuse are very high. The rates of bullying are very high.”

Wallace quickly agreed to be the subject of Haas’ film. His mother was more ambivalent, both about the film and the changes her child is undergoing.

“In our hearts, you’re Rachael,” Suzy Reinke, who grew up in a liberal Presbyterian family in Texas, says early in the film. “That’s what we’ve known you as, and that’s a hard habit to break.”

Haas said that ambivalence captures a facet of the issue that’s rarely seen publicly. Most depictions of LGBTQ youth involve parents who are either “the perfect model parents,” she said, or their opposites — they’ve kicked the kids out and cut them off.

“We so rarely see families who go through a journey and who don’t get it right at the beginning, and work towards that and get to a place of getting to love a transgender kid,” she said. “That is so important, because it’s a journey that a lot of us make about a lot of different things.”

Haas said she’s “so grateful” that the family let her film “when things weren’t so pretty, because I could see it was going to be OK. And I knew that witnessing the process while it was happening was really powerful.”

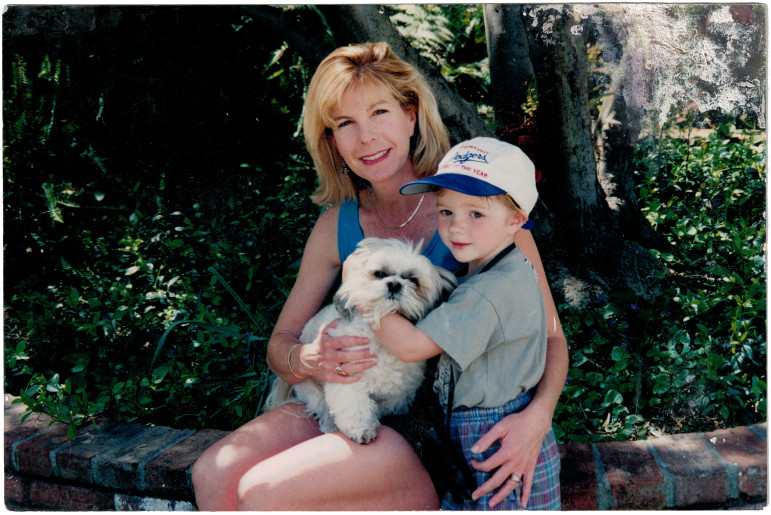

Real Boy

Mother Suzy Reinke with him as a child.

The film also illustrates how technology — particularly the spread of online video — gives today’s transgender youth insights that previous generations haven’t had.

“For Joe, when he came out as trans, he tells this wonderful story about how the only place he’d ever heard of a transgender person was on one of those horrible Maury Povich-like shows,” she said. “It was always very salacious, and that was his only experience of it.”

Stevens still struggles with sobriety in the film, and while his family is seen warmly welcoming both Bennett and Suzy, they had their own struggles to get through.

“Fortunately, over the years, things have very much improved. Their family is lovely and very supportive,” Haas said of Stevens’ family. “The family you see in this film is a family that’s been through a lot, but is also in a place where they’re able to really connect. They’re in the film in part to give you a sense of where Suzy can end up.”

This story has been updated.

More related articles:

Report: NYC Criminal Justice System Needs to Reform How It Treats LGBTQ Youth

Time to Foster Safety, Well-Being, Permanency for LGBTQ Youth