By Francine T. Sherman and Annie Balck, in partnership with the National Crittenton Foundation and National Women's Law Center

.

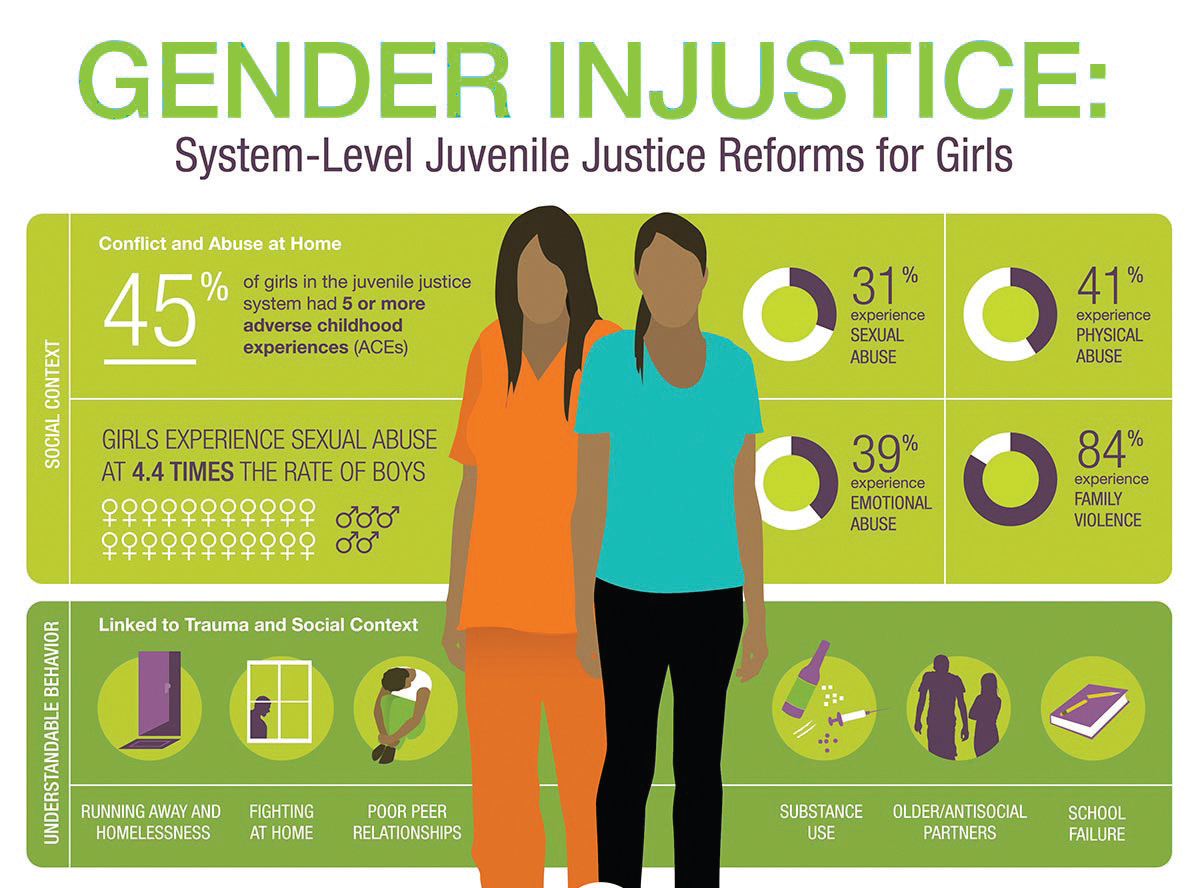

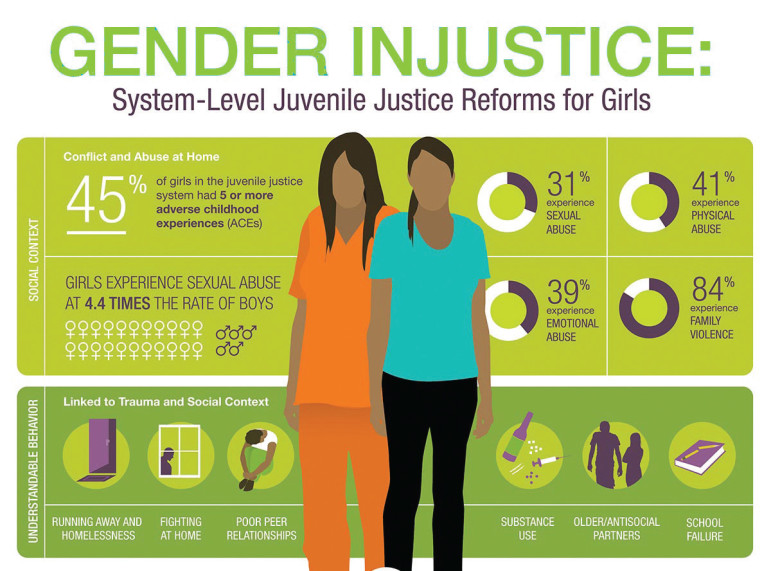

One of the starkest statistics in the lives of girls today is that 73 percent of girls in the juvenile justice system have been physically or sexually abused, according to U.S. Bureau of Justice figures.

A report last summer referred to this as the “sexual-abuse-to-prison pipeline.”

Experiencing abuse is one of the major predictors of girls themselves getting into trouble, according to the report published by the Human Rights Project for Girls, the Georgetown Law Center on Poverty and Inequality, and the Ms. Foundation for Women.

The most common crimes for which girls are arrested — including running away, substance abuse and truancy — are also the most common symptoms of abuse, the report noted.

“Girls are pretty invisible” in current efforts to reform the juvenile justice system, said Stephanie Covington, a psychologist who provides training and consulting services to criminal justice agencies through the La Jolla, California-based Center for Gender and Justice.

“People don’t talk about the girls,” she said.

Most people are really surprised to learn that the proportion of girls in the juvenile justice population is increasing, Covington said. They are surprised at the level of abuse girls have suffered and the prevalence of trafficking.

Organizations that work with girls — from community organizations to juvenile justice agencies — need to respond to the conditions of girls’ lives, Covington said.

They need to recognize and work with the trauma that underlies the behavior of many girls, and they should take an approach tailored to girls’ needs, she said.

Girls who are harmed by sexual violence but who have economic stability, adequate schools, safe neighborhoods and access to mental health services tend to be buffered from further harm, according to a Crittenton Foundation report released last October.

“For girls at the margin, the experience of sexual violence often funnels them into the juvenile justice system,” the foundation’s report said.

Each year, 578,000 girls are arrested, according to the foundation.

From acting out to helping out

In the seventh grade, Regina (not her real name) began getting in trouble in her Broward County, Florida, middle school. She began cutting classes. She quit doing schoolwork. She also got into fights.

“I was being violent,” she said.

After one fight with another girl, she was arrested and had to appear in juvenile court.

She was sentenced to a nine-month community-service diversion program.

But when she went back to school in the eighth grade, not enough had changed.

She then entered the day program at PACE Center for Girls, a Florida nonprofit that offers schooling, counseling and life skills training.

PACE, which stands for Practical Academic Cultural Education, takes a gender-responsive and trauma-informed approach, emphasizing healthy relationships, good decision-making and communication skills. It also engages each girl’s family in an effort to support motherdaughter relationships.

The program focuses on self-respect, self-confidence and issues of sexuality.

“The actual environment is different,” Regina said. The classes are smaller and the teachers are nicer, she said.

In a big high school they wouldn’t even know your name, Regina said.

“Here they actually care about you,” she said.

At PACE, Regina learned to trust people again, and she delved into the issues that underlay her aggressive behavior in school.

“My counselor helps me with my self-esteem,” she said.

Not only did Regina re-engage in school, she came to care about the other girls and the adults at PACE. And she developed a career goal.

She’s interested in forensic science and wants to run her own business helping adults and kids who have been traumatized by sexual abuse.

“I want to help them find justice,” she said.

Photos by Pace Center for Girls, Inc.

The PACE Center for Girls in Florida takes a gender-responsive approach in working with girls at risk for delinquency. The program focuses on creating a safe environment that celebrates strengths.

Dealing with delinquency

PACE’s 19 centers serve girls at risk of delinquency. Fifty to 60 girls attend each center.

In 2008, the Annie E. Casey Foundation called PACE “the most effective program in the nation for keeping adolescent girls out of the juvenile justice system” in the foundation’s Kids Count report.

Twenty-eight percent of girls at PACE have had a prior arrest. Three-fourths are failing in school. Nineteen percent have been physically abused, 17 percent sexually abused, and 23 percent emotionally abused.

In addition to providing a caring environment, nurturing relationships, counseling and life skills training, PACE connects girls with the larger community.

Regina, for example, said she really benefited from the opportunity to meet new people. Girls go on field trips and meet adults doing work that interests the girls.

One field trip was to a forensics lab, which sparked Regina’s interest.

“I learned from two of the forensics workers” how they find fingerprints and gather information from blood spatters, she said.

“I’m really motivated,” she said.

“I hope to find a job in a forensics field,” she said.

Nurturing environment

When Melinda Patterson appears in court these days, it’s as a criminal defense attorney. However, as a youngster, she saw court from a different angle — a kid brought in for truancy and fighting.

Patterson was a straight-A student in elementary school. However, her mother worked nights, and when she was a teenager Patterson had little supervision. “I was left to my own devices,” she said. She had also experienced abuse as a small child.

By the ninth grade, she barely attended school. But when she transferred to PACE, she responded to the relationship-focused environment.

She describes it as nurturing and caring — and nearly impossible to skip class. Not only was the building locked during school hours, but if a student went missing “10 people would be out looking for you,” Patterson said.

Students did not slip through the cracks; rather, they were held accountable, Patterson said.

“It was life-changing when I started holding myself accountable,” she said. “It just finally clicked that I needed to do this for me. It was really up to me.”

With only 15 or so girls in a class, teachers could adjust the teaching to meet student needs, Patterson said.

“Every teacher knows every student’s back story, their home life and everything that’s going on,” she said. Under their tutelage, Patterson was able to graduate from high school a year early at age 17.

Students from PACE speak at the 2016 All About Girls Summit in Jacksonville, Florida. The summit brought together policymakers, funders and girl-serving organizations from across the country to address the needs of girls.

A movement for girls

PACE recently convened a nationwide “girls summit” in Orlando, bringing together out-of-school organizations such as Girls Inc. with the Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention and foundations including the National Crittenton Foundation and NoVo Foundation.

The gathering challenged the lack of response to the needs of girls,” said Mary Marx, president and CEO of PACE. It sought to begin a nationwide girl movement, she said.

The Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention in the U.S. Bureau of Justice is also pushing for a genderspecific and trauma-informed approach within the juvenile justice system. Three years ago it launched the National Girls Initiative to provide resources to state, local and tribal groups.

Several states including Florida, Hawaii, Connecticut, Oregon and Minnesota now require their juvenile justice systems to specifically address girls’ needs. In Hawaii, for example, a separate girls court in the state judiciary’s First Circuit provides counseling to girls and their parents for a year in effort to strengthen relationships and address the issues that brought the girls to court.

A gender-responsive approach

In a webinar hosted by the Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention in 2013, Covington presented six “guiding principles” for taking a genderresponsive approach to working with girls at risk for delinquency.

The first is to acknowledge that gender makes a difference, she said.

“If you are working in an agency, a program or a juvenile justice system that believes that it does not make any difference whether you are treating boys or girls, it means that there is a good chance you will not get good services for girls,” she said in the webinar.

The environment is second: It should be based on safety, respect and dignity. “The environment is critical,” she said. It is not enough to acquire a curriculum labeled “gender-responsive,” Covington said. The environment has to become gender-responsive and new staff attitudes must be developed.

Relationships are important. A program should promote healthy connections with a girl’s important relationships.

Services should be comprehensive, she said. The specific socioeconomic needs of girls should be considered and promoted. For example, is the organization addressing the needs of pregnant and parenting girls to continue their education and gain job skills?

The number of girls who are pregnant in the U.S. juvenile justice system is unknown, but research from local systems shows that around 30 percent of girls are or have been pregnant in those systems, according to the Human Rights Project for Girls “sexualabuse- to-prison pipeline” report.

Finally, comprehensive community services are needed, Covington said.

“Once a girl has a trauma history, this is highly associated with alcohol and drug use, high-risk sexual behaviors, sex work, physical and mental disorders,“ Covington said.

So a program for girls must be traumainformed, she said.

“This would be an agency or program that has an understanding of trauma. They avoid any kind of triggering of trauma reactions, and they make adjustments in the organization so those who are trauma survivors can actually benefit from the service they are trying to provide.”

The program must understand both trauma triggers and self-calming strategies, she said.

It really creates a culture shift within an organization, Covington said. Regina could easily have become a statistic in the juvenile justice system. In the seventh grade, she was acting out aggressively and was headed for further trouble.

But nurtured in a trauma-informed program designed to address the needs of girls, she blossomed, addressing her feelings, developing empathy for others and turning her skills and interests into actions that benefit her and others.

Now 15, Regina successfully ran for student government president at the PACE center she attends. Her platform in the election: “How may I help you?”