The room was silent. Twelve probation officers sat silently in a circle. Some glared at the floor, some looked at the ceiling. The African jembe drums sat, one in front of each PO, a silent invitation. As the lead drummer began, they started to play along, hands gently against the taut skins of the drums, a whisper. Then a thump, then some missed beats, louder, a faltering rhythm, then laughter. One hour later, 12 POs were shaking the roof as they drummed together, beaming at each other and making music.

In our public schools and in our daily lives, or for young people in detention, too often we view art — writing, painting, music, theater — as an add-on, a luxury, something to be brought in only if we have the time or money. But in Los Angeles County, a groundbreaking collaborative is turning that idea on its head. The Arts for Incarcerated Youth Network is reframing the arts, not as a feel-good bonus, but rather as the foundation for building wellness, health and resiliency in our young people — particularly those caught up in the justice system.

>> OST HUB: Program Quality <<

Small beginnings

Three years ago, the Violence Prevention Coalition of Greater Los Angeles began convening folks who provide arts-based programming to incarcerated youth. The groups ranged from organizations teaching kids to write, direct and act in their own plays to deeply reflective personal writing, but the groups shared common challenges and larger goals. We started small, with a few joint presentations about the importance of arts as a means to process trauma, as a healing-informed practice.

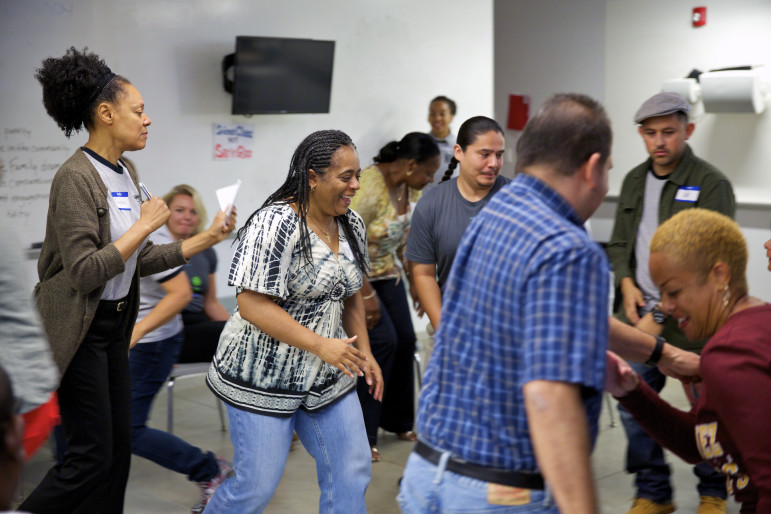

Momentum built quickly. By 2014, the group convinced more than 70 county probation officers to come to a full day of hands-on experiential training day. The deputies acted out goofy improv exercises, joined in focused circles writing a group poem and sat together in the theater, their hands in sync as they drummed ancient tribal rhythms. They shared the struggles and challenges they face through presenting improvised scenarios to the larger group, and amazingly, they shared all this with alumni of the programs — young people who had once been part of their caseloads.

[Related: Ferguson Puts Chess in Schools to Help Students]

We know from their evaluations that every single one of them moved from regarding the importance of arts-based programming neutrally, at best, to seeing arts-based programs as an important tool in turning around the lives of incarcerated youth. We had proved through practice the effectiveness of working together to achieve common goals. Out of that experience, the Arts for Incarcerated Youth Network was born.

Modeling partnersip: A force in the field

During the past year, the Arts for Incarcerated Youth Network (AIYN) has evolved from an idea to an emerging force in the field, modeling partnership among eight (and counting) community-based organizations and, between public and private partners, collectively serving more than 1,000 young people per year.

Most recently, we contracted with the Los Angeles County Probation Department to provide arts programming to nearly 100 kids across six detention camps six days per week for four weeks.

This project was an extension of the Children’s Defense Fund’s venerable Freedom Schools program, an innovation driven by the probation department, with the partnership of the Los Angeles County Arts Commission. AIYN activists joined probation staff in a weeklong training at the CDF’s headquarters in Knoxville, Tennessee.

We got to know and even like each other, establishing common goals and a shared sense of purpose. In the detention camps, the arts curriculum was provided on a rotating basis at each site, so that all student scholars have the opportunity to experience multiple arts disciplines during the four-week period. AIYN teaching artists adapted their organization’s previous curricula for this pilot project in order to build intentionally upon the principles, themes and goals of the Freedom Schools.

Resiliency-building for young people and probation staff

One week, the students were focusing on “I Can Make a Difference in Myself,” so the teaching artists focused on self-reflection.

“If you really knew me,” one student wrote, “you’d know that I hate my shadow because it reminds me of my dark past … If you really knew me, you’d know I like purple orchids and wildflowers. If you really knew me you’d know you’re the reason I’m scared to love.” At the end of each week, students shared their work with the rest of the camp, often prompting more students to engage the following week.

Yet, part of what makes AIYN unique is that members are committed not just to providing arts as a resiliency-building tool for young people, but also as a resiliency-building tool for probation staff. We recognize that probation officers also carry trauma, and that building connection and shared experience through the arts among both staff and youth can improve the system for everyone.

There is no other collaborative like this in California. It’s already being looked at as a model for the state, and could be a model for the nation. It is the only place where arts-based organizations working with incarcerated youth come together for a common purpose and coordinate. By coordinating among multiple partners, we’re able to provide comprehensive programming at scale, and across the county, while also supporting a shifting culture within probation. This partnership between a strong network of community-based organizations, LA County Probation and LA County Arts Commission could establish a model for the state and the nation as a whole.

At its core, AIYN is demonstrating through practice the power of working together and of putting arts at the core of rehabilitation and resiliency building among young people and those who work with them.

Kaile Shilling is executive director of Arts for Incarcerated Youth Network. In addition to having volunteered as a teaching artist in AIYN member programs, and several years working in theater and in the film industry, she has nearly two decades of experience working in and with nonprofits.

Kaile Shilling is executive director of Arts for Incarcerated Youth Network. In addition to having volunteered as a teaching artist in AIYN member programs, and several years working in theater and in the film industry, she has nearly two decades of experience working in and with nonprofits.

More related articles:

How After-school Programs Can Impact Kids’ Screen Time