Photos courtesy of Road Map Project

Eben-Ezer Yanez (center) and Freda Crichton (right) work with filmmaker Angie Bernadoni (left) from Reel Grrls on videos featuring stories of young people. The YouTube-style videos will provide information about local programs helping young adults return to school or get on a path to a job.

Several years ago, Freda Crichton, now 21, found herself floundering. She and her twin sister dreamed of entering the Marine Corps.

After they finished high school in Seattle, her sister was accepted into the Marines, but Crichton was not.

Crichton tried Bellevue College in Bellevue, Wash., for two quarters and then left— and she didn’t quite know where to turn.

A friend suggested Year Up.

The one-year intensive training program is dedicated to closing the gap in opportunity between low- and high-income young people. At Year Up, Crichton gained information technology skills and ended up with several job offers. She also developed a strong desire to help other young adults find their path.

Crichton’s concern dovetails with a major social challenge facing young people today.

No job, no school

One out of every seven young people ages 16 to 24 in the United States is not in school or in a job, according to the U.S. Census Bureau’s American Community Survey.

The numbers are higher in the Southern states, where the percentage is 15.5 percent, according to a March 2015 report by the Cowan Institute at Tulane University.

“They number in the millions and they are often forgotten by our society,” noted a 2012 report by John Bridgeland and Jessica A. Milano. Once termed “disconnected youth” — and often disparaged as dropouts — this group now has a new designation: opportunity youth.

Bridgeland and Milano first used the term in their report “Opportunity Road: The Promise and Challenge of America’s Forgotten Youth.”

Bridgeland sat with a group of young people in the YouthBuild program, which helps young adults get a high school equivalent diploma and gain job skills.

Some of them had been in prison, some on the streets, some had been homeless, some in and out of foster care.

“I sat there and listened and was overwhelmed again by their charisma and resilience,” he said.

[Related: Low-Income, Homeless Teens Use Art for Job-Readiness]

“If they can be hopeful, why can’t the rest of us?” he thought.

“I’m not a person to paper over reality,” Bridgeland said, but these young adults represent an opportunity, both in their own lives and to society as a whole.

However, one million of these 5.8 million young people did not get a high school diploma, according to Opportunity Nation, a national bipartisan think tank seeking to expand youth economic mobility. Some are struggling to find work. Others can’t afford the increasing cost of college. Others have personal problems, including 15 percent who have a disability, according to Opportunity Nation.

Nicole Yohalem is director of the Opportunity Youth Initiative at the Road Map Project in Seattle and King County, Wash., which aims to increase the number of students on track for college or jobs.

“We have thousands of young people … leaving the K-12 system prior to graduation,” she said.

“It’s a huge problem here. It’s pretty daunting.”

The region, the home of Microsoft and many other technology companies, dramatizes the gap between a youthful population without enough education and an economy in which people must be highly skilled to fill today’s jobs.

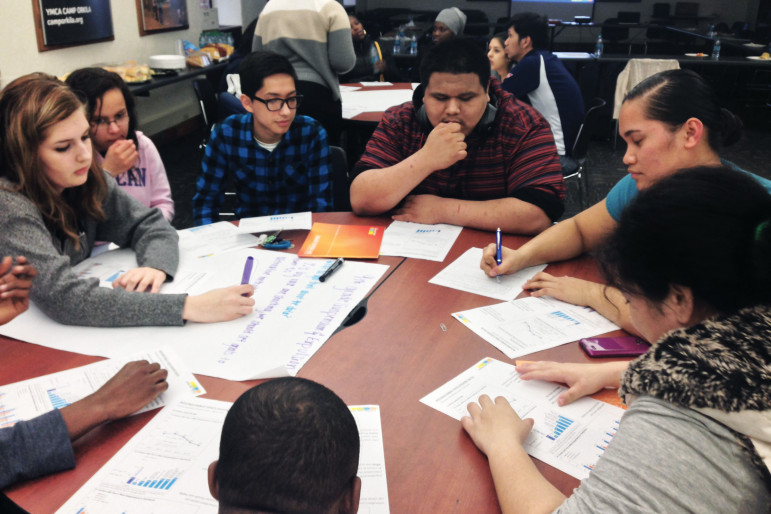

Members of the Opportunity Youth Advisory Group for the Road Map Project in Seattle analyze school discipline data. The advisory group helps guide the project in building systems to reconnect young people to school and living-wage work. Second from right is Freda Crichton.

Creating a collective impact

In 2010, the White House Council for Community Solutions was organized to seek ways for nonprofits, businesses, government and members of the public to work together on community problems, including the “highly vulnerable population of 16- to 24-year-olds who were disconnected from school and work,” Bridgeland said.

The council discovered that young people described as disconnected don’t view themselves that way. They have energy and ambition but lack pathways to succeed, according to the council’s final report.

It recommended action in four areas:

- Establish collaborations among nonprofits, employers, schools, young people and others.

- Create a sense of national responsibility and use data to identify effective programs.

- Engage youth as leaders.

- Create more on-ramps to employment.

The conference brought new visibility to the needs of many young adults and galvanized a number of organizations and businesses.

The Gates Foundation, for example, made a number of one-time grants to groups including the Forum for Youth Investment, Opportunity Nation and the Aspen Institute, said Steve Patrick, executive director of the Aspen Institute’s Forum for Community Solutions.

The Aspen Institute united 100 leaders of 80 organizations — and created the Opportunity Youth Incentive Fund, providing up to $13 million for 21 community partners nationwide.

The goal is to create community collaborations that will make a collective impact.

“It’s really the systems that are disconnected — not the young people,” said Patrick, referring to school systems, institutions of higher education, workforce training programs, the juvenile justice system, employers and others.

“All of those systems need to be in the same boat, rowing in the same direction,” he said, to impact the opportunity youth population.

Monique Miles, deputy director of Aspen’s Forum for Community Solutions, said a large part of the work is to identify policies that create barriers for opportunity youth.

“You bring together system leaders and ask: How is inequality baked into this policy?” she said.

A community college, for example, might reconsider its admission test. Employers might look at transportation barriers or child-care needs some youth face, she suggested.

Building systems in King County

The Road Map Project and its Opportunity Youth Initiative are among the programs funded by Aspen.

Yohalem, who directs the initiative, said its goals are to improve the supply, quality, access to and coordination of re-engagement programs for youth.

“We saw the emergence of an opportunity not to build just a program here and a program there but a strong system of pathways that are coordinated,” Yohalem said.

“We think we may have as many as 20,000 opportunity youth in the region,” some who finished high school and others who didn’t, she said.

“With a problem of that magnitude, programs here and there are not going to solve it.”

It doesn’t make sense, she said, for 20 different programs to be doing the same work when some of those functions could be centralized — transportation, fund development, employer engagement and outreach, for example.

Another goal is to have programs embedded on community college campuses and in community-based organizations for students who didn’t finish high school. Most young people do not want to return to high schools they left, she said.

Youth and language

The Road Map Project has made a point of engaging young people as leaders.

Eben-Ezer Yanez serves on the youth advisory council, along with Crichton.

In high school, Yanez was a good student, athlete and leader. But he arrived in the United States from Honduras when he was 9, and he was undocumented.

“I wasn’t able to just go straight to a four-year [college],” he said. “I realized that no matter how much I worked, at the end of the day I still didn’t have [some] opportunities.”

He’s currently working four part-time jobs while waiting to get a visa. He hopes eventually to attend the University of Washington and pursue a career in medicine.

He and Crichton, an AmeriCorps VISTA member, are creating videos about three programs that help young people reconnect to school or get on a path to a job: iGrad, Seattle Youth Source YouthBuilders and the Seattle Multi-Service Center.

Both Yanez and Crichton like the term Opportunity Youth.

“That’s exactly what it is,” Crichton said, “… young people with an opportunity.”

“Young people are never disconnected,” she said. “They are connected and engaged in something,” whether those things are bad or good.

“Opportunity youth means someone who has a chance to be something else, something bigger” but for various reasons just couldn’t yet, Yanez said.

Yohalem also sees value in the term.

“It speaks to the opportunity that our community and our society is missing out on because we’ve failed to bring these young people back into the fold.”

More information:

Opportunity Youth are defined as youth ages 16 through 24 who are not connected to school or work.

- 28.5 percent have left high school without a diploma.

- 23.7 percent have some college education.

- 14.6 percent have a disability.

- 33.4 percent have worked in the past year.

- 30.0 percent of the women have children.

By race/ethnicity:

- White: 11.3 percent

- African-American: 21.6 percent

- Asian-American: 7.9 percent

- Hispanic: 16.3 percent

- Other: 15.3 percent

Source: “Reconnecting Opportunity Youth.” Tulane University Cowan Institute for Public Education Initiatives, 2015.

Don’t call them dropouts

Based on a survey of 3,000 young people and interviews with more than 200, students who leave high school before graduating:

- are more resilient than popular opinion and current research literature describe.

- often struggle with overwhelming life circumstances that push school attendance far down their priority lists.

- need fewer easy exits from the classroom and more easy on-ramps back into education.

- emphasize how much peers, parents and other adults matter to them.

And …

- Connectedness to others is a high priority for young people and can lead to or away from school.

- Young people who interrupted their high school education often “bounced back” from difficult circumstances, but individual resilience was insufficient to re-engage with school. Longer-term positive development required additional support.

Source: “Don’t Call Them Dropouts: Understanding the Experiences of Young People Who Leave High School Before Graduation.” a report by America’s Promise Alliance and the Center for Promise at Tufts University, 2014.

More stories related to this one:

Ex-Gang Member’s Life Does a 180 After He Joins Los Ryderz

‘Our Kids’ — How One San Francisco Program Gets Teens Off Drugs

Opinion: Overcoming Hopelessness for the Next Generation

Rewriting Education Law: Senate Replaces ‘No Child Left Behind’

How to Explain and Protect Youth of Color From Police Misconduct, Trauma