RU Ready for Work

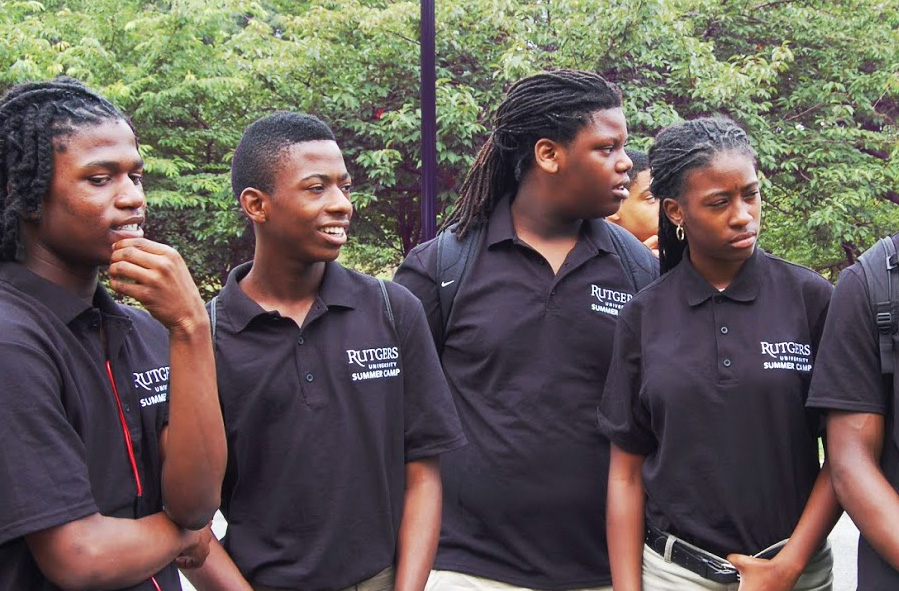

Students participating in a summer program by Rutgers University-Newark.

NEWARK, N.J. — When 19-year-old Malik McNeil runs into former schoolmates from the two high schools he attended here in Brick City, usually they don’t have much good news to share.

“A lot of my peers got caught up in a lot of things,” McNeil said, listing an assortment of felonies, including robbery and burglary, which he says his former schoolmates have done time for. “Their situation is not the best.”

McNeil, a sophomore and prospective business management major at Kean University in Union, N.J., believes, “They wish they went down the same road I went down.”

He’s talking about the road paved by RU Ready for Work, a youth development program created and administered by the Office of University-Community Partnerships, or OUCP, at Rutgers University-Newark.

It provides participants with college advice that regular school counselors often cannot, cash incentives of $100 per month during the school year, and part-time summer jobs for six weeks that pay minimum wage. Launched in 2008 as a “demonstration model,” the RU Ready for Work program has become one to watch.

Newark is mulling plans to use it as a training program for other organizations that want to help young people from economically disadvantaged backgrounds get prepared for college and entry into the workforce, program officials say.

At least one other nearby school district — East Orange, N.J. — has expressed interest in implementing the program there, they added.

A leading college access expert says the RU Ready for Work model holds great promise for increasing the number of young people who enroll in college.

“I think if we’re going to solve issues around increasing college attainment and closing gaps in attainment across groups, we really do need the involvement of a whole range of different players in this,” said Laura W. Perna, a higher education professor at the University of Pennsylvania, and founding executive director of the Alliance for Higher Education and Democracy, or AHEAD.

“Higher education institutions are one of those players, especially since higher education institutions set the rules in terms of what’s required in the application process, for financial aid, academic progress,” she said. “So to the extent to which higher education institutions can be sharing that information with folks in schools, especially schools where parents haven’t gone to college and are lacking other resources to get up to speed on what these requirements are, higher education institutions can play an important role in that way.”

The RU Ready for Work program is financed largely with Workforce Investment Act funds, now known as Workforce Innovation and Opportunity Act funds, that are distributed through the Newark Mayor’s Office of Employment and Training. As its name suggests, the program was originally intended to help prepare young participants for the world of work.

As participants began to express interest in certain careers, it soon became apparent that post-secondary education had to become part of the equation, said Diane Hill, assistant chancellor at Rutgers University-Newark.

“If this is the job you want to do, this is the path, and it requires college,” Hill said, explaining the shift the program took in its work and messaging to young participants.

“It requires something other than just going to work,” she said. “If you’re going to make career decisions, you have to understand what that journey is about. So we started to have them map out success plans. They had to actually say, ‘I’m going to do better.’” Doing better meant taking advantage of the program’s recommendation of tutoring and its offer of SAT prep.

So while work readiness remains an important focus of RU Ready for Work, the program could just as easily be called RU Ready for College.

Many of the program’s metrics are focused on college enrollment, records show. And so far, the results look pretty good.

Despite uncertain funding, which has made it difficult for program administrators to plan much further than a year ahead, those who complete the program enroll in college at an average rate of 82 percent — much higher than the historic rate of 48 percent at West Side High School.

That’s where the program began in 2008 to address the “overwhelming evidence of disproportionate disadvantage.” West Side is in one of the most impoverished census tracts in Newark.

The 82 percent average rate comes from 2009 (when the rate was 56.3 percent) through 2014 (when the rate was 100 percent for the second year in a row). The rate includes not only West Side High School but several others to which RU Ready for Work has since expanded.

The program size ranges from 19 to 22 each year.

The summer component of the program has earned mostly high marks from the National Summer Learning Association, particularly for its emphasis on college acceptance rates and underemployment in Newark.

“The program mission and vision are clearly grounded in the needs of the community,” says a 2013 NSLA report, which gave the program a 3.5 out of a possible 4 for its purpose, and similarly high marks for its planning, partnerships, and integration of an academic and developmental focus.

A more comprehensive evaluation of the program is in the works.

Program officials track those who complete the program — 87.6 percent from the program’s inception through 2014. That’s 105 out of 120 students, including those who don’t go on to college. Program officials are required by Newark to track students for one year after graduation.

However, program coordinator Tiffany Walker says, “We do make ourselves available to provide support and resources to former participants beyond the required year.” This is particularly so for participants who remain engaged in the program, serve as volunteers, or enroll at Rutgers Newark, she said.

Besides Walker, the program is run by one other program coordinator, who is also an adjunct at Rutgers; an assistant director, and a curriculum specialist. A city grant funds 1½ of the positions; the others are donated by the university.

Program participants don’t have to be high fliers, but they must have a minimum GPA of 2.0. Students often hear about the program by word of mouth, Hill said.

That’s how McNeil, the Kean University student, got involved when he was about 14 at West Side High School.

“I heard through one of my friends from RU Ready,” McNeil said. “So I took it upon myself to get in the program.” He got involved at a critical time in his family’s life.

His mother, who had been working in food service at an alternative school in East Orange, N.J.,was out of work. He never knew his father until 2013, his senior year in high school.

“Before then he wasn’t there for my whole life,” McNeil said. “We had to actually find him and when we found him he was on his death bed.”

His childhood neighborhood is in ZIP code 07106, where just about every felony, including rape and murder, is higher than the average in Essex County.

McNeil felt it was his personal responsibility to do something to help lift his family out of poverty. He has two sisters, one older and one younger.

Asked what he did with the $100 monthly stipends, he just smiled and shook his head. “That’s how we stayed afloat,” he said. He typically bought food or clothes with the money. He remembers having to wear his summer clothes in winter.

“Like, you’re really at the breaking point and that stipend came just in time …” McNeil said. “I don’t know if they understand how much it helped.”

Hill admits at first she didn’t understand why young people would need a cash incentive to participate in a program designed for their benefit.

“I used to think they should want to do it. We shouldn’t have to give an incentive,” Hill said. But her perception changed once she began to ask students what kinds of things might hinder their program participation. Many indicated they had to work after school to pay school fees or buy their own shoes.

“Students are kind of thankful that they have this incentive attached to it,” Hill said. “To me, it’s a simple fix to be able to give them an incentive to say if you do this, if you commit, this is what we’re going to give you guys at the end of the month. And I think that it’s a minimum for a lot of the work that they’re doing.”

Perna, the professor at the University of Pennsylvania, agreed.

“Students have to figure out a way to have their basic needs met before they can even begin to think about college,” Perna said. “The one potential benefit from the stipend could be it’s enabling these students to engage less in paid employment. If they’re spending less time working, they have more time hopefully to engage in getting academically ready for college.”

Hill said the stipends are included in the annual per student cost of RU Ready for Work, which she put at $3,000 to $4,000. Students are also given bus tickets to get to after-school programming at Rutgers.

One recent seminar stressed the importance of applying for scholarships to lessen the college’s financial burden.

“I recommend that high school students should start looking at different ways to finance your education,” said Michael Dillard, one of the two program coordinators for RU Ready for Work. “Those [tuition] bills will add up and you won’t even see it coming.

“Financial aid will only cover so much,” continued Dillard, also an adjunct professor in the School of Public Affairs and Administration at Rutgers University-Newark. “So what else are you going to do in terms of financing that education?”

He advised the students to search for and apply for scholarships, and to write the required essays — even if the students dread writing — to at least try to lighten student loans. He assigned them to research at least two scholarships and be prepared to do a presentation on each at the next seminar.

Dillard is available to the students for more than just the seminars.

In fact, one West Side High School senior credits RU Ready for Work in general — and Dillard in particular — with doing more to help her get through the college search and application process than her regular high school counselor.

“People don’t really prepare inner-city kids for the college application process,” said Lakeisha Bright.

“A lot of us are the first generation in our family to go to college,” she said. “It’s not like we can get help from our parents.

“Guidance counselors are always like, ‘Did you apply to this college?’ Not, ‘Do you know how to?’”

Lakeisha said Dillard paired her with a female college student — who was also an RU Ready for Work alumna — to help her fill out college applications.

“They gave us deadlines to do everything,” she said. “They were really, like, on us.”

Lakeisha has been accepted into a number of colleges but is leaning toward Kean University.

Research indicates that such help is one of the most effective things that schools can do to help students get into college — but many high schools don’t provide such help.

“She has the persistence to succeed but she needs that coaching along the way,” Dillard said.

He sees part of his job as making sure high school seniors have a smooth transition to college — something that regular high school counselors are often not positioned to do.

“One of the biggest things that students continued to complain about is high school guidance counselors are way too overwhelmed,” Dillard said. “… The caseload is increasing and they just don’t have the individual focus to put into the student.”

He said he is able to build rapport with school counselors and spur them to get routine things done promptly — such as sending transcripts — that students may not have as much success with.

Hill, who oversees the program, concedes it has “procrastinated” on stepping up to the plate to become a training model because she wants to make sure “everything is in place” to do the job well.

And while the program has done a good job of getting students into college, questions remain about how much time and emphasis the program is able to put on helping students apply to the best-fit colleges where they can persist and succeed.

The lack of data on such issues is a problem that exists in much of the college access field, according to Perna.

“There are gaps in knowledge about what we know about the effectiveness of different models,” she said.

And there are also questions about whether there are more economically efficient ways to achieve the same results.

“There will always be competing pulls on available resources,” Perna said. “A question anybody has to ask is what’s the return on this particular investment compared with using the same amount of money for a different type of way.”

At Kean University, McNeil is studying similar questions. In his case, they are about his plans to use a degree in business management to start a clothing line.

“I just look at a business degree is me learning the backbone of the business,” McNeil said. “It’s not me being more artistic or innovative. It’s just learning the economics, the accounting, how should I read the contract or just learning everything economically, so we won’t be naive to what we can get.”

See sidebar “Campus Jobs Make College Familiar for High Schoolers in Program”

This article is also appearing in the NJ Spotlight.