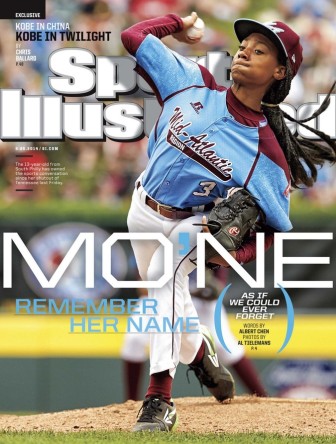

Mo’ne Davis, the 13-year-old girl from Philadelphia who captivated a sports audience with her pitching in the Little League World Series in August, has the perfect name for what is going on in youth sports these days:

Mo’ne Davis, the 13-year-old girl from Philadelphia who captivated a sports audience with her pitching in the Little League World Series in August, has the perfect name for what is going on in youth sports these days:

“Mone-tization.”

Kids who play sports are being monetized by businesses, colleges and entrepreneurs, and Mo’ne was just the latest prize for fortune hunters. She was promoted heavily by ESPN, which has the broadcast rights to the Little League World Series.

A baseball signed by Mo’ne fetched $510 on eBay.

The extreme is the $60 million contract ESPN has with Little League Baseball Inc. to broadcast the Little League World Series through 2022.

Then there is the money train for professional sports teams, particularly in baseball, which attracts more kids than professional football or college football. The baseball playoffs are underway and the grandstands are full of children craving a hot dog ($8) or souvenir hat ($20).

The rest of the story is the haul being made by hitting and pitching coaches who pull in $70-$110 an hour for lessons, travel baseball teams (regional, full-time teams) that charge $2,000 to $5,000, and the football camps, baseball camps and soccer camps, not to mention the pressure on parents to buy the latest apparel and gear.

In addition, recreation complexes for youth sports are popping up all over the country that charge as much for admission as a minor league baseball park. And don’t dare try to walk in with a $1 bottle of water. The gatekeepers will stop you because they want you buying the $3 bottle inside to help meet their cost projections.

The Sports Facilities Advisory, which tracks youth sports participation for those complexes, estimates the economic impact of youth sports at $7 billion per year. Various studies of youth sports claim there are 35 million participants ages 7 to 18.

There is a lot of money to be made from parents and their children.

Not all the monetization of youth is exploitative. Far from it, but parents and mentors have to be aware how much is too much.

Most parents, if they could afford it, would rather spend heavily on a travel baseball team or a summer basketball team than pay a lawyer to get a wayward teen out of jail because they had nothing better to do than vandalize property. What’s an $800 fee to play high school baseball five days a week compared with a teenage boy coming home to an empty house after school — with a girl — and the trouble that can follow from that?

What’s a $70 hitting lesson if it can enthuse a teen about baseball and keep them from settling in front of the TV or computer for the evening?

There is also the matter of getting greater enjoyment from the game, and sometimes that costs, too.

Bill Melvin, a youth pitching coach in the Atlanta area, has a thriving business teaching proper mechanics to pitchers as young as 6. How much fun is it for a youngster who gets to go to the mound to pitch like his TV heroes, and throws ball after ball out of the strike zone? It can be disheartening.

A professional pitching coach can iron out the pitching motion so the ball finds the strike zone. Happiness follows, both for the pitcher and the teammates who do not have to stand behind him and watch batters walk to first base after four balls.

“It’s not only learning mechanics, it is learning how to throw so they don’t hurt themselves,” said Melvin, who has coached 35 Division I pitchers in his 15 years as a private instructor, and many other children who will not play college ball. “It is about enjoying the game more. If you are taught to hit properly and throw properly, it is more fun.

“It’s more than instruction, if you find the right professional instructor. It is building self-esteem, being a good teammate. It is using baseball to facilitate the true meaning of life, which is sacrifice, teamwork, hard work and how to deal with adversity.”

Melvin charges $250 for a package of four 30-minute lessons. Scott Barfield thought it was worth the investment for his 11-year-old son, Rainier, especially because the boy was so competitive.

“I grew up playing tennis and it’s a game where you need to know the fundamentals to play at a competitive level,” Barfield said. “I enjoyed playing competitively, and he wants to play at a competitive level, but I played tennis; I didn’t know how to teach my son how to pitch.

“I have no visions of grandeur here, I don’t even know if he is going to play baseball in college, much less pro ball. But it is great to get out here together and learn the fundamentals. I also think we have reduced the chances of him getting hurt by learning the proper way to throw.”

Patrick O’Connor was worried about exactly that, injury, when he signed up his 9-year-old son, Ian, for pitching lessons. When Ian threw, he would drop his elbow and throw sidearm, which stresses the elbow. A few lessons with Melvin and Ian’s elbow was up and he was throwing himself behind the ball, reducing stress on his arm.

“Ian thought he knew everything about throwing just by watching it on TV, but there are proper ways to do things,” Patrick O’Connor said. “His team was practicing one hour a week and he loves the game and seems to do well at it, but he needed some more instruction.

“I have no complaints at all about spending the money.”

So where is the sweet spot? How much money should parents devote to youth sports?

“Problems arise when parents start to look at their kids’ activities as an investment,” said John Engh, chief operating officer of the National Alliance for Youth Sports (NAYS), in an e-mail. NAYS, which is based in West Palm Beach, Fla., is one of the country’s leading advocates for positive and safe sports, working with 3,000 community-based organizations.

Engh said the parents’ argument is “We just spent an entire summer and $XXX on this training so you need to keep playing lacrosse.”

“And in that regard, someone who invests more than they can afford, whether it is time, money or both, is going to probably have unrealistic expectations and thus, get unacceptable results. The main question always is are the parents doing it for themselves or are they doing it for their kids?”

The money haul in youth sports is especially noticeable when it comes to “travel teams,” those squads of elite players who might leave town for national tournaments or barnstorm around the city. Usually, the coach is a paid professional.

The tournaments cost $400 to as much as $2,000 (Perfect Game tournaments in baseball), and travel teams feel they have to have the latest uniforms, which drives up costs even more.

What’s worse than the cost, according to Engh, is the travel team pressure.

“There’s the situation when the parent sees an impressive team and has a child marginally talented who is not too driven or competitive, who may love playing a sport, and they force the child to sign up and try out, thinking that they will become more talented and more driven, and that rarely happens,” Engh said. “Often that child ends up getting more turned off by the game. Plus, at the travel team level coaches are going to play the best players, so some kids may be looking at a long season on the bench with minimal game action.”

That is not to say an investment is not worth it for some young athletes. Stiffer competition brings out the best in athletes. That can cost money.

But the cost can be worthwhile when it brings joy. Thomas Chiu, 9, had just finished a hitting lesson with a paid instructor at Medlock Park in Decatur, Ga. He could not sit still talking about what it means to be able to hit correctly.

“When you know how to hit and get a hit, you have a better chance to score,” Thomas said. “If you have a better chance to score, you have a better chance to win.

“Hitting and winning is fun.”