Two brothers enrolled in an after-school program participate irregularly – daily one week and then not at all the next. The program manager notices they stuff non-perishable snacks into their pockets each evening before the program closes – exceeding the provisions of the program by sneaking as many granola bars and pretzels as they can.

A 14-year-old straight-A student hands a freshly completed original essay to her after-school supervisor. She’s proud of her prose – and the maturity she must demonstrate in living alone with her twin brother while her mom stays down the street with her boyfriend.

A 13-year-old arrives to her after-school program with a backpack and a hardened determination to find someplace safer to stay: Grandma, she tells the program staff, has just hit her with a two-by-four because she broke a serious house rule.

These are all cases of neglect and abuse – which must be reported to child protective authorities.

By the numbers

Child abuse is horrific, but unfortunately it’s not uncommon. According to the National Child Abuse and Neglect Data System (NCANDS), Child Protective Services in the U.S. received an estimated 3.4 million allegations of child abuse and neglect involving 6.2 million children between Oct. 1, 2010, and Sept. 30, 2011. More than three-fifths (60.8 percent) of those allegations were screened in (found worthy of further investigation), and about 20 percent of the cases investigated found evidence of abuse or neglect, resulting in 676,569 children found to have suffered substantiated abuse and neglect, some more than once.

More than three-quarters (78.5 percent) of the substantiated cases involved neglect, while 17.6 percent involved physical abuse and 9.1 percent sexual abuse. A case could involve more than one type of abuse.

Because NCANDS only collects data on allegations reported to official authorities, and the actual rate of abuse is considered to be much higher. For instance, the World Health Organization, relying on surveys of adults which asked about abuse and neglect experienced in childhood, found that 25 to 50 percent of adults report being physically abused as children, and about 20 percent of women and 5 to 10 percent of men report being sexually abused as children.

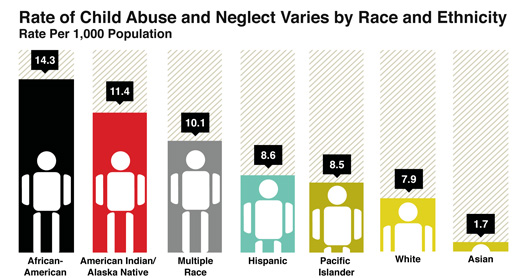

Child abuse and neglect cuts across gender and racial lines: NCANDS data show that 48.6 percent of victims were male and 51.1 percent female in FFY 2011, with 43.9 percent of victims white, 22.1 percent Hispanic, and 21.5 percent African-American. However, rates of abuse and neglect were highest among children of African American (14.3 per 1,000), American Indian/Alaska Native (11.4 per 1,000) and mixed (10.1 percent) racial heritage.

Children in all age categories suffer from abuse and neglect, but youngest children are the most likely to be victims: Children under one year had the highest rate of victimization, at 21.2 per 1,000 population, as compared to 3.7 per 1,000 for 17-year-olds. The most common perpetrators of abuse and neglect were parents (81.2 percent).

Youth workers already know that effects of child abuse can be long-lasting — from physical to emotional and cognitive harm. Children who were abused are at greater risk for a number of adverse consequences as adults, including lower educational achievement and higher rates of depression, alcohol and drug abuse, smoking and risky sexual behaviors.

What’s mandatory?

In the U.S., mandatory reporting laws, intending to prevent and limit child abuse, are set at the state level. Although each state has one or more laws addressing this issue, the details about who is required to report, as well as the procedures to do so, vary widely from state to state.

In all U.S. states and Washington, D.C., anyone who suspects child abuse or neglect is allowed to report it, but in only 18 states is anyone who suspects abuse or neglect required to report it to the authorities. For some professions, such as primary and secondary education and health care, mandated reporting is universal or near-universal, but for many other professions the laws on reporting vary widely.

For instance, 27 states require members of the clergy to report suspected child abuse, 17 designate probation and parole officers as mandatory reporters, 12 require professional photograph and film processors to report, but only four states mandate reporting from employees and volunteers at institutions of higher education. Some states allow anonymous reporting, while others require that mandatory reporters supply their name and contact information, and only in some states is the reporter’s information held confidential.

Child abuse commonly under-reported

Determining how many children suffer from abuse is difficult because, despite mandatory reporting laws, many cases go unreported. Summarizing a number of studies looking at child abuse in high-income countries, including the U.S., Ruth Gilbert and colleagues report that some scholars estimate that 10 percent or more of children suffer physical abuse, and several times that suffer sexual abuse. Gilbert’s summary, published in The Lancet in 2009, also found evidence that found that even among children being monitored by child protection authorities, official records underreported the amount of abuse that occurred.

Because the signs of child abuse and neglect are often ambiguous (see sidebar), those who work with children and adolescents must make a difficult decision about whether to report based on what may seem like scant evidence. Even physicians, who have more familiarity with evaluating physical symptoms than most youth workers, tend to underreport suspected abuse.

Flaherty and colleagues, writing in “Pediatrics” in 2008, found that primary care physicians treating children with suspicious injuries reported only 24 percent of cases in which abuse was a possible cause, and only 73 percent when abuse was a likely or very likely cause. “Suspicion” is a somewhat ambiguous concept, and physicians varied in how confident they wanted to feel before reporting a case of suspected abuse: For some, 10 percent confidence was sufficient, while others wanted to be 90 percent confident before reporting.

Physicians were more likely to report suspected cases of child abuse when they were not familiar with the patient and his or her family, and if the case had been referred to them as a potential case of abuse. In addition, Flaherty and colleagues speculated that some may only report cases they feel will be substantiated by child protective services, so that suspicious major injuries are more likely to be reported than minor injuries, even though a child presenting with repeated minor injuries is a pattern associated with ongoing child abuse.

In practice, it seems that mandatory reporting laws are seldom enforced, and punishments are often light. A recent case in Los Angeles points to this reality. Students and parents complained to school authorities as early as 2002 that Robert Pimentel, a fourth grade teacher at George de la Torre Jr. Elementary School, was touching female students inappropriately. However, no action was taken by the principal, Irene Hinojosa, or any other school official, until October 2012, when parents took their complaints to the police.

In California, failure to report suspected child abuse is a misdemeanor punishable by a fine of up to $1,000 and/or six months in the county jail, but Alison Filo, a prosecutor in Santa Clara, told Vanessa Romo, reporting for KPCC (Southern California Public Radio), that her county had prosecuted only two cases of failing to report in the previous 20 years.

In a separate case reported by Romo, a teacher failed to promptly report a student’s report of abuse by a family member. Although the teacher was convicted of failing to report, her sentence consisted of 20 hours of community service and one year’s probation.

In the Pimentel case, although Principal Hinojosa retired as the process of firing her was underway, and two other school officials were reassigned, none were charged with failing to report child abuse.

There are many reasons while many cases of child abuse go unreported. Marchand and colleagues, writing in the European Journal of Pediatrics in 2012, note that most abuse (an estimated 80 percent or more) is perpetrated by parents and guardians. Professionals interacting with children are likely to see, at most, the consequences of abuse, and the signs may be ambiguous signs (such as bruising), or there may be no physical traces at all (see sidebar).

In addition, some professionals may be worried about the consequences of reporting suspected abuse, an act that may bring a child into contact with a social services system that doesn’t always function as well as it should.

Sarah Boslaugh, PhD, MPH, is a Youth Today staff writer. The second edition of her popular statistics handbook, “Statistics in a Nutshell,” was recently released by O’Reilly, and her next book, “Health Care Systems Around the World: A Comparative Guide,” will be published later this year by Sage.

Youth Today Contributing Editor Rachel Alterman Wallack contributed to this story.