WITH REPORTING BY SARAH AMANDOLARE, LINDSAY ARMSTRONG, CRAIG GIAMMONA, DARYL KHAN, AND CHRISTINE STRIECH

NEW YORK–Trayvon Martin wasn’t from any of New York City’s five boroughs, but his death and the acquittal of the man who shot and killed the unarmed teen after a confrontation in a gated community courtyard in Florida, nine states, one capital, and nearly 1,200 miles away, resonated with many residents — black, white, and Latino — as if he was one of the city’s own.

Across the city and the state, New Yorkers who were on quiet, contemplative strolls in the park, who sat in the pews of churches, who shot baskets on the city’s storied basketball courts said they were gripped with thoughts, both philosophical and visceral, as they reflected on the death of Martin and what many saw as the unjust but seemingly implacable decision reached by a jury Saturday evening that let the teenager’s killer go free.

Reaction to the acquittal of George Zimmerman for the shooting death of Martin ranged from quiet frustration, embittered resignation, and overwhelming sadness. Some conceded that the jury was left with little option and that it was the fault of a Kafkaesque criminal justice system that legally permits an armed adult to kill a child; others expressed their rage on the avenues of Manhattan and made calls for a type of street justice that has no place in a courtroom.

In a statement, New York City Mayor Michael Bloomberg, one of the nation’s leading gun control advocates, said Martin’s killing and Zimmerman’s acquittal are the result of laws that encourage people with guns to take justice into their own hands.

“Sadly, all the facts in this tragic case will probably never be known,” Bloomberg said. “But one fact has long been crystal clear: ‘Shoot first’ laws like those in Florida can inspire dangerous vigilantism and protect those who act recklessly with guns. Such laws – drafted by gun lobby extremists in Washington – encourage deadly confrontations by enabling people to shoot first and argue ‘justifiable homicide’ later.”

But in Union Square Park, just after 6 p.m on a sweltering Sunday night, a rancorous crowd of protesters who had gathered to protest the verdict pointed to something deeper than the law or the American criminal justice system for the Zimmerman decision. The animated crowd said they blamed the same pernicious culture of racism that expresses itself in stops and frisks on the streets of New York for the exoneration of a killer in Sanford, Fla.

“New York is a global city that sets the standard for the rest of the world,” said Aimee Lang, 26, an organizer for ColorofChange.org. “We’re hoping to amplify our voices so the world knows we will only stand for justice for Trayvon Martin, incidences and tragedies will not go unnoticed, and we will not be silent.”

A few dozen protesters pulled hoodies over their sweat-drenched heads despite the suffocating humidity, others wore buttons and stickers with hoodie silhouettes. Signs peppered the crowd with black and white images of the young, slain Martin.

Many at the rally said they met to express their feelings of rage, sadness and confusion at Zimmerman’s acquittal. Rival activist groups came together in solidarity, calling for an end to racial profiling, the NYPD’s stop-and-frisk policies, and for the U.S. Department of Justice to charge Zimmerman with a civil rights violation.

As the crowds burgeoned, the protesters began to spill onto Broadway, and following what seemed to be a secret cue, several of them linked arms to block oncoming traffic, forcing cars and taxis to sit and wait as thousands of demonstrators marched on Broadway chanting “No Justice, No Peace,” “Justice for Trayvon,” and “The people, united, will never be defeated.”

For the next hour the demonstration snaked along Manhattan’s avenues and streets until it reached Time Square, bringing traffic to a standstill.

There were 15 arrests related the protests, most of them at Times Square.

Not everyone in the city expressed their disgust at the decision by taking to the streets. Some walked in parks, others attended church services and others, like Jay Liataud, spent the day hanging out.

Liataud said he wore it as a symbol — to underscore what he thought was the blatant injustice of the decision.

“I wore it because Trayvon Martin wore a hoodie and George Zimmerman thought he was suspicious because he was a black man in a hoodie,” he said.

Liataud, who first learned about the case from a YouTube video, said he watched the trial closely on the news and, and tried to remain neutral and as the evidence was introduced and the arguments were presented. He was watching television last night as the verdict was read.

“It hurt, but I just got to accept it. I wanted to see Trayvon get justice,” he said. “A teenage boy got shot and I just think,’That could be me.'”

Parents spoke about the difficulty of having to balance their personal outrage at the outcome of the case with the pragmatic consequences they said of being the parents of dark skinned children. Carla Rivera explained that she already worries about her son as he gets older. She has already had talks with her nine-year old son about how he could be perceived differently in less diverse parts of the city.

“You worry about him going into certain neighborhoods so I have to talk to him about that,” she said as she watched a baseball game in Inwood Park. “My son is darker skinned than me so that could have been him in that hoodie. I tell him that you always have to been on the alert.”

She added that with Martin’s shooting and the Zimmerman verdict that kind of a talk is a necessity.

“It’s a frustrating reality, but it is reality.”

Like Rivera, J.J. Joseph, 37, said he did not follow the case closely. Partly because he had a dispiriting sense that it was a foregone conclusion that Zimmerman would be acquitted. He said the case has made him scared for his son Jaron, 12, who he was walking with in Prospect Park sunny Sunday afternoon. He said the decision, regardless of the legal minutiae and the rules governing the particulars of the trial, was hard to see as anything but “straight up racism.”

“I can’t say I’m surprised. I don’t know what that says, but no, I’m not surprised,” he said shaking his head with resignation. “He was an innocent kid. It’s 2013, and this guy is walking away for killing an innocent kid.”

Steve Addl (pictured at left), 27, is one of many who took the news of the verdict personally. Addl, who has a daughter who lives in Florida, said the jury’s decision to let Zimmerman walk cheapens his life and the life of his daughter.

“That could be her,” he said, pausing from a workout in Fort Tyron Park in Washington Heights to discuss the case. “And I feel like now I know what the value of my life is in this country. A couple of years ago Michael Vick went to jail for dogfighting for 23 months so now it’s like you’re telling me that my life is worth less than a dog’s.”

He said he frequently is stopped and frisked or pulled over and harassed by the police. He saw a deep connection between the way young black men in New York City are treated by the criminal justice system here and the outcome in Sanford, Fla.

“I pretty much thought it was an open and shut case. I mean there’s a dead kid and there’s a guy with a gun. You put two and two together and you hope it equals four.”

Many across the city, like Cheryl Willis, 29, a resident of Flatbush in Brooklyn, said the Martin shooting and Zimmerman exoneration had echoes of two fatal shootings of two young black men by the police department — Sean Bell and Ramarley Graham.

“People want to blame the crazy laws down there, but this has happened here and it keeps happening,” she said. “Something’s wrong when an innocent 17-year-old gets shot and nothing happens.”

In both the cases of Sean Bell, 23, who was shot by detectives on the morning of his wedding on Nov. 25, 2006, and Ramarley Graham, 18, who was shot and killed in his bathroom by police officer Richard Haste, the officers walked. A Queens jury found the plainclothes detectives who fired a fusillade of 50 bullets at Bell and his friends were found not guilty; and Haste’s case was tossed in May by Bronx supreme court justice Steven L Barrett because of a mistake made by the Bronx district attorney’s office.

Outrage and frustration with the case resonated outside the city limits. In Mansion Square Park, a rundown public space in economically struggling downtown Poughkeepsie, about three dozen people came to the park and formed a protest circle. The park had been a meeting place for people tracking the case as it unfolded on television. Now with the verdict in they gathered in the patchy grass, outfitted with a few shoddy benches and surrounded by old row houses with chipped siding and sagging porches, and took turns articulating their disgust.

“I’m sick of it,” said Mae Parker-Harris, an activist from Poughkeepsie. “A lot of the history of this country is a bunch of lies. That’s why I’m speaking like this. We got to tell the truth, and if we don’t speak the truth we deny our children the truth. It was a white courtroom and that’s what we got: a white conviction.”

Karen Coleman, 57, a Poughkeepsie resident, threw her hands in the air as she talked about the verdict.

“What do we tell our children?” she said. “They can’t go outside if they’re black? They can’t go to Florida?”

Sharon Froelich (pictured at left), 60, who came from across the Hudson River to join in the impromptu rally, was active in protesting the Vietnam War and participated in the Civil Rights Movement. She carried a sign that read “No Justice, No Peace” and wore a straw hat to protect her from a blazing sun. She said the Zimmerman verdict shows the country has a long way to go to secure social justice.

Sharon Froelich (pictured at left), 60, who came from across the Hudson River to join in the impromptu rally, was active in protesting the Vietnam War and participated in the Civil Rights Movement. She carried a sign that read “No Justice, No Peace” and wore a straw hat to protect her from a blazing sun. She said the Zimmerman verdict shows the country has a long way to go to secure social justice.“I see so little progress,” Froelich said. “It’s just as bad today.”

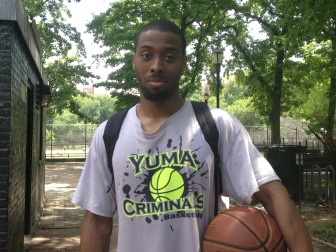

Sean Pickett (pictured below) said he sees Martin as other young black men whose killings became touchstone’s for civil rights, like Emmett Till, Amadou Diallou and Sean Bell. He said he and his friends are still victims of the same kind of racism that drove Zimmerman to profile Martin when they are stopped and frisked, or when they have their bags searched on the subway.

“It seems like they only stop minorities,” he said, choosing his words carefully at the Inwood Hill Park Basketball Courts. “I don’t walk around thinking that the police are after me or that the world is against me, but I am aware that I am a young, black man in America and that the odds are against me.”

Some of the protesters who took to the streets later in the evening in Union Square said they hoped to change those odds by giving their children a civics lesson in real time. Jannett Bykov, 40, marched along confidently with her four-year old daughter Brooklyn keeping stride at her side. The Crown Heights, Brooklyn resident said it was important for her to not only come protest the verdict, but to bring her young daughter along as well.

“Is it futile, possibly, but at least I expressed how I felt,” Bykov said. “I didn’t sit home and cry. And now my daughter’s experiencing something that might mold the rest of her life.”

Several parents chose to make the march a family affair — for Rahkejian Brooks from the Bronx, that meant three generations. Brooks attended the demonstration with her son, Troy, 14, her daughter, Shaquana, 25 and Shaquana’s son, Amir, 4. She said it’s important to practice the freedoms of speech and expression, and she believes in the power of passive resistance.

“This is the future and it will be our children’s reality and their children’s reality if we don’t change it now,” Brooks said.

Her son Troy, who wants to be a lawyer, said he had followed the trial and that he and his friends had worn hoodies to school and carried skittles in their pockets.

“It could happen to any of us,” he said. “In the future, when I have children, I’ll pass this all down to them.”

During morning services across the city, it wasn’t protests, but prayer people turned to, to find some solace in the wake of what they saw as a devastating verdict. Many pastors used the acquittal as an opportunity to expound on the limits of the workaday justice churned out in the courts in Sanford, New York and the rest of the country.

At Emmanuel Baptist Church on Lafayette Avenue in the Clinton Hill neighborhood of Brooklyn, pastor Rev. Anthony I. Truffant encouraged the kind of protest that would occur later in the night. He encouraged action; but his frustrations transcended the failures of human institutions.

“Like the blood of Trayvon Martin, we continue to cry out how long must we live in a land that does not care for us,” he implored from his pulpit. “Why Lord? How long do you continue to tread on the path to the slaughter? Why? How long, Lord, would you continue to hold your justice from our lives? God it’s hard to search for words to say to you.”

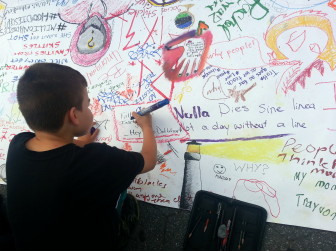

Photo captions, from the top: Protesters left this memorial for Trayvon Martin at the rally in Union Square Park on Sunday (Christine Streich / New York Bureau/JJIE), Protesters at Union Square Park Sunday. The protest soon turned into a march to Times Square (Christine Streich / New York Bureau/JJIE), A boy at the Union Square Park protest Sunday (Christine Streich / New York Bureau/JJIE), Steve Addl, 27, has a daughter in Florida. He was working out on the parallel bars at Fort Tyron Park (Lindsay Armstrong / New York Bureau/JJIE), Sharon Froelich attended a rally Sunday at Mansion Street Park in mostly black downtown Poughkeepsie (Sarah Amandalour / New York Bureau/JJIE), Sean Pickett, 26, at the Inwood Hill basketball courts (Lindsay Armstrong / New York Bureau/JJIE)