Through boldly inked outlines, soft watercolors, pull-out posters and digital canvases, a new crop of mixed media artists are breaking complex social issues into bite-sized, accessible morsels. From Damascus to Honduras, and even to New York City, these creators are mixing journalism with the comic book format to immerse and engage readers.

Works of comics, or illustrated, journalism are lush, multilayered, and offer new gleanings to readers upon repeat views. They are simultaneously journalism and art in a comic book format, and they are transforming the way the public consumes information.

The creators and organizations associated with this new trend are all committed to comics as a means of furthering the journalistic process. To them, works of “reportage illustration” represent a strong future for journalism, and result in a public that is engaged in vital conversations about issues as complex as the criminal justice system or international affairs.

Comics have the unique ability to pull the reader into a complicated story with savvy, clever visuals. They increase user identification with characters in the story, and, because we can absorb information across multiple channels, they make it easy to dive into something as complicated as student debt and private education—or as culturally important as libraries. Comics make the world easier to understand. They make it easier for readers to learn — and as a result, make it easier to take action.

Comics have the unique ability to pull the reader into a complicated story with savvy, clever visuals. They increase user identification with characters in the story, and, because we can absorb information across multiple channels, they make it easy to dive into something as complicated as student debt and private education—or as culturally important as libraries. Comics make the world easier to understand. They make it easier for readers to learn — and as a result, make it easier to take action.

Comics are also a powerful draw for young readers, and as such, create easy educational entry points. They are one of the few forms of printed work that are increasing in demand and educators are taking notice. Educators have been documenting the benefits and challenges of using comics as classroom tools since the 1940s. But in the last several years, a number of libraries and educational associations have launched events dedicated to fostering learning through comics, including conferences such as Comics, Libraries, and Education: Literacy Without Limits, which is organized by New York state’s Monroe County Library System, or the Pennsylvania College of Technology’s Wildcat Comic Con, which promotes the uses of comics in the classroom.

In 2006, Maryland Public Schools launched a comics in the classroom pilot program in which 53 percent of teachers strongly indicated that they would want to use the program again, and only 11 percent of students said they had no desire to use the program again.

Should we consider any quotes from traditional journalist leaders or think groups – like Columbia Journalism Review or Pointer Institute – or Medill School of Journalism – about the relevance of this type of journalism today? Do traditionalists or schools of journalism agree that comics is a valued part of the information sharing media mix or do they believe it dilutes journalism in some way?

And I think you need a nutgraph here relating to the field of youth development. Why is this piece in Youth Today, as opposed to the Center’s newsletter or annual report? (I don’t mean to sound dense, but YT is marketed to youth practitioners – so you may need to drive home the relevance.>

Why Comics?

Sarah Glidden, a non-fiction comics creator and journalist, says that comics are a powerful tool for identification and engagement. Glidden is currently creating a book about working as a journalist in the Middle East, and also wrote and illustrated How to Understand Israel in 60 Days or Less, a graphic memoir and coming of age story about Glidden’s birthright trip to Israel. She is currently working and living in Angoulême, France as part of a comics residency program at Maison des Auteurs.

“There’s a lot of good writing out there, and people get overwhelmed and tune everything out,” Glidden says. “Comics journalism can almost trick people into reading about something that they wouldn’t normally read. Iraqi refugees are the most unsexy thing, but if you make a comic that’s pretty, [people will] read it, know about the issue, become connected to it, and maybe be engaged on a deeper level in the future.”

“It was only a few years ago that comics journalism was one of the novelty things that only one or two people were doing,” says editorial cartoonist Matt Bors. “Now it has a genre that seems to have been recognized in larger media.” Bors is the editor of Cartoon Movement, an international hub for editorial cartoons and comics journalism, where he has published works by both Glidden and Dan Archer (mentioned below). Bors was a finalist for the 2012 Pulitzer Prize and won the 2012 Herblock prize for editorial cartooning.

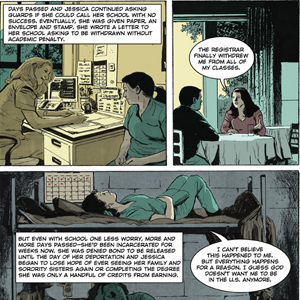

Bors is also collaborating with the Center for Sustainable Journalism (the publisher of Youth Today) on a project titled Jessica Colotl: In the Eye of the Storm about a young woman’s struggle with immigration authorities. It will be published this month.

Another subhead – Engaging Readers or A Democratizing Force

Last year, Bors visited Haiti with other Cartoon Movement staff to commission a graphic novel on the reconstruction efforts that would be authored by Haitian journalists and drawn by Haitian cartoonists. The resulting 70-page book is being published in installments at Cartoon Movement.

Bors is deeply aware of his role as an artist and editor in the creation of this work.

“When working in comics you are interpreting visually for people…, so in some sense you have more control over what a reader sees than you would in prose,” Bors says. “I suppose the thing to be conscious of is that you are editing, visually, with what you choose to depict and omit, from landscapes to someone’s expression. People can linger over a single image and draw a lot from it, so I always try to be aware of the mood I’m transmitting and trying to remain true to what happened.”

Today’s wave of comics isn’t just ink and paper. New creators are harnessing the power of the web and tablet devices to merge multimedia elements—such as sound, animation, and outside links—to create highly immersive works that appeal to a wider variety of audiences.

“Comics have a versatile power to put people in a situation and simultaneously give them an overview,” says Dan Archer, an interactive comics journalist who crafts multimedia explorations of international human rights issues. “They require reader engagement and participation to make sense of them. It’s not just a question of hitting a play button.”

Archer’s breakthrough moment came in 2009, when he released a comic book history of the Honduran Coup. The comic was a wild success when it was first released and connected hundreds of people in an international issue. “It was watershed moment for me and really blew my mind,” Archer says. “The comic got translated into eight languages. … When people get a scent for something powerful and effective, the democratizing force of the Internet shows through.”

Archer’s Graphic History of the Honduran Coup – a look at the 2009 coup in Honduras and the historical context of U.S. intervention in Central America — was also an early indicator of the visual-first trend that is sweeping the social web as organizations like JESS3, UpWorthy, and 59 Liberty pump savvy educational infographics, captioned photographs, and other enticing items through Facebook, Twitter, Pinterest, and Tumblr.

From Whence it Came

Illustrated and comics journalism have a strong history in our country. While today’s practitioners are capitalizing on the power of the web and social sharing to connect with new audiences, visual communications have been around for some time.

“Visual has always been the medium through which we communicate with the biggest number of people,” says Chris Olson, founder of 59 Liberty, a design studio in city, state, that seeks to combine the rise of comics and infographics with savvy social marketing.

“Within American history, you have all of these great stories that were told [with visuals], because folks couldn’t read, so we had Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper in the 19th century,” says Olson.

The form is so intrinsically tied to media, in fact, that in 2011, On the Media host Brook Gladstone partnered with comic journalist Josh Neufeld to publish The Influencing Machine, a graphic history on how media influences culture (and vice versa). Neufeld and Gladstone take special care to highlight the works of illustrated correspondents such as Theodore Davis, who created illustrated representations of the Civil War and other key American conflicts for publications such as Harper’s Weekly — even though Davis was not present at many of the events he illustrated.

According to Gladstone and Neufeld, Davis and his cohorts’ work was so influential that “General William T. Sherman, appalled by this army of ink-stained wretches, [banned] them from the front.”

Contemporary greats include the likes of Harvey Pekar, who documented middle class life in the series American Splendor, or Joe Sacco, a cartoonist and journalist of international renown whose new book is simply titled Journalism, and features a collection of Sacco’s reportage from conflict zones around the world.

Making a difference at home

Comics and illustrations aren’t just effective tools for reportage from conflicted areas. They can also be utilized to inform and transform the lives of everyday people. For example,New York’s Center for Urban Pedagogy, or CUP, embodies the power of the visual.

CUP uses smart design and illustration to interface directly with communities whose information needs go unmet, such as street vendors and juvenile offenders.

Infographics, maps, comics, and other visually-based information delivery methodologies “work at different levels,” according to Christine Gaspar, executive director of CUP. “People process visual information differently; you can process more visually.”

In 2010, CUP produced and released a comic called “I got arrested! Now What?,”which was produced in partnership with New York’s Center for Court Innovation, The Youth Justice Board, the NYC Department of Probation, and Danica Novgorodoff, a comic book creator and designer for graphic novel publishing house First Second.

“Now What” was developed over nine months as a part of CUP’s Making Policy Public program, which seeks to bridge information gaps between public policy makers and those who are most affected by public policy.

The booklet is a comic and fold-out poster that navigates the ins and outs of the juvenile justice system in plain language and savvy visuals, and is distributed to juveniles who are arrested in New York State. It’s a clever update on Goofus and Gallant, the old comic about manners from Highlights magazine, and is making a difference for young people who enter the juvenile justice system. The comic received a 2010 PASS (Prevention for a Safer Society) award, and has been distributed broadly both in print and as a PDF file.

Linda Baird, who worked with members of the Youth Justice Board on this project, has seen the comic’s success in action. “We have been able to present the comic around the city. Probation, our intended audience for the comic has been distributing it for two years now,” Baird says. Good – but how do we know it’s making a difference for youth?

According to Baird, the comic has been used to train AmeriCorps members, and “people even like it to train adults!” Assemblymember William Scarborough has also used the comic to teach classes at CUNY.

“Whenever we go out to recruitment events…, we bring copies of it,” says Baird “Anytime anyone sees it who is in this youth policy justice world at all, they seem to have a use for it.”

“We’ve sold 30,000 copies of the publication to the Department of Probation,” says Gaspar. “[The Center for Court Innovations] had a few thousand copies in their first print and just reordered 1,000. CUP has distributed several hundred copies. And it was downloaded from our website over 35,000 times in 2011 alone.” The coordination between CUP, the community affected by juvenile incarceration, and the courts systems has exemplified best practices– in a complex field where collaboration can be a challenge.

To better craft the narrative of the comic, CUP “interviewed folks at all levels about their roles in the juvenile justice system,” says Gaspar. The booklet required a lot of discussion to achieve the “right balance between legal descriptions and layperson conversation. We spent a lot of time with words to make them work.”

Illustrated journalism requires intention and purpose, something that CUP imbues into each step of the production process. “All of the visuals we produce are targeted toward a specific audience, … and the language is crafted in a way that it’s talking to them,” Gaspar says.

Danica Novgorodoff was drawn to the project because it offered an opportunity to create something that was in service to a specific audience—one in need of information presented in a non-threatening way.

“If you were to give a kid a piece of paper that says ‘you’ve been arrested and this is what to expect and there are 10 paragraphs [on a sheet of] paper,” Novgorodoff exhales with gusto. “I mean, I wouldn’t read that.”

“The images give you a way to visualize the world or the process,” Novgorodoff says. “You can’t get that from a heavy block of text, especially if you’re 16 and scared. You aren’t going to pull out a dictionary and look up every word you don’t understand.”

IS there any way to interview a kid who says the graphic approach works and isn’t condescending?

Novgorodoff believes, as many creators do, that comics have a unique power to transmit information and ideas to readers. “I love comics because there are endless possibilities. You can create something that’s all images and no words, but still tell a story. You can use heavy narration or a lot of dialogue. There is so much room for experimentation. When you pair words and images together, they really compliment each other. The words can say a lot the images can’t, and the images can say a lot the words can’t.”

EDITOR’S NOTE: Erin Polgreen has worked with many of these creators as contributors and advisers to Symbolia, a forthcoming magazine of comics journalism that will be available on the Apple iPad in September.

Erin Polgreen is the founder of Symbolia: The Tablet Magazine of Illustrated Journalism. You can follow Erin on Twitter (www.twitter.com/erinpolgreen)