When is a three-day suspension simply three days out of school, and when is it the first step into the school-to-prison pipeline?

More and more, scholars and researchers are concluding that getting into trouble and having trouble learning are intertwined – most suspensions these days stem from relatively minor conduct infractions – but the experts haven’t decided whether the misbehavior or the trouble learning comes first. And they don’t know whether either or both contribute to black students being punished more frequently and more harshly than white students.

.jpg) U.S. Department of Education statistics show clear disparities: A survey by the department’s Office for Civil Rights found black students were three and a half times more likely to be suspended or expelled than white students during the 2009-10 school year. The survey covered public schools attended by 85 percent of all students in the United States.

U.S. Department of Education statistics show clear disparities: A survey by the department’s Office for Civil Rights found black students were three and a half times more likely to be suspended or expelled than white students during the 2009-10 school year. The survey covered public schools attended by 85 percent of all students in the United States.

Other Education Department numbers show blacks lag about 5 percentage points behind whites on test scores, a gap that has remained fairly static since the late 1980s. For the previous 15 years, black students had been narrowing the gap.

Although relatively recent zero tolerance policies have been blamed for high dropout and incarceration rates for black youth, research has found that unequal treatment started long before those policies.

In their article “The Achievement Gap and the Discipline Gap: Two Sides of the Same Coin?” Anne Gregory, Russell Skiba and Pedro Noguera conclude that suspensions increase the disconnection between marginally achieving youth and their schools, causing the students to be “less invested in school rules and coursework and, subsequently, less motivated to achieve academic success.”

Of course, said Ivory A. Toldson, senior research analyst for the Congressional Black Caucus Foundation, suspensions are often used to punish the very actions that signal students are already disengaging: being late to class or missing assignments, not paying attention in class or falling asleep.

Rather than one causing the other, “the two gaps can really feed on each other,” leading to a snowballing effect on students, said Gregory, an associate professor of psychology at Rutgers University. She said black students are more likely to be cited for “defiance,” and her research is trying to determine why.

The toxic combination of punishment and tuning out starts early for boys. Oscar A. Barbarin III, a psychology professor at Tulane University and an expert on the achievement gap, said many young boys are naturally boisterous and prone to roughhousing, which puts them out of sync with teachers who want children to sit down and be quiet.

“Because of their behavior, they are subjected to more discipline, which begins then to sour their taste [for] school,” he said.

A long-simmering problem

A 1975 study by the Children’s Defense Fund was the first major report to show that a disproportionate number of black children are suspended, compared with other children. Since then, according to Indiana University professor Russell Skiba, research has consistently shown black students are punished more often and more severely than white children. The fact that this story is told again and again, and nothing changes, alarms Skiba.

“Why don’t we have hearings in front of Congress? If there is a racial difference, we ought to be doing something about this,” he said in an interview.

Ten years ago, Skiba’s research began to answer the question of whether the harsh treatment of black children is deserved.

His team investigated the racial divide, using records from an unnamed large Midwestern public school system. The researchers found that the underlying reasons teachers sent black middle school children to the principal’s office were different from those for white children.

In his 2002 report, “The Color of Discipline”, Skiba contrasted the offenses cited for black students: “disrespect, excessive noise, threat, and loitering” to offenses cited for white students: “smoking, leaving without permission, vandalism, and obscene language.”

Skiba concluded black students were disciplined in situations that were “more subjective in their interpretation” than for white students.

A later study where classrooms were observed suggested some black students were unfairly punished by some teachers.

Researchers observing young schoolchildren and their teachers felt “indignation, disgust, [and] sadness” at incidents they witnessed of black children being unfairly singled out for punishment, wrote Barbarin, of Tulane, in a 2006 article in Young Children, a professional journal published by the National Association for the Education of Young Children. In contrast, he said, breaking the rules was tolerated for white children.

Barbarin said prejudice did not taint the interactions of all, or even the majority of, classrooms under observation and, more often than not, teachers treated their students with fairness and warmth. But when children were mistreated, it was troubling to witness. “Boys of color were under constant restriction and hardly ever got to play on the playground. [For punishment, the teacher] would make them sit quietly at picnic tables in the hot sun for 30 minutes,” wrote one researcher.

Barbarin concludes that some teachers overreact and misinterpret boys’ behavior as hostile or challenging, rather than playful.

Youth Today findings

An analysis of recent suspensions in Texas by Youth Today raises questions of whether the teachers’ actions are untainted by race.

Texas – the site of a landmark study of discipline in schools released last year that showed 60 percent of seniors had been suspended or expelled during middle school or high school – has tried to reduce the overall number of disciplinary actions. Youth Today’s analysis of suspensions since the larger study shows that the changes made after had no impact on the so-called discipline gap between races. The overall number of suspensions fell, but black children still received proportionally more suspensions and expulsions than white children.

The finding is consistent with a nationwide study of elementary and middle schools at which “positive behavior supports” using praise and positive reinforcement have improved the school environment in general, but have not been successful in reducing the racial disciplinary gap.

The Texas data, obtained through an open records request, show that suspensions of all students fell 13 percent after the school disciplinary code was amended in 2007, taking into account such factors as learning disabilities.

But the racial gap remained as large as before in cases that allowed teachers and administrators to make judgment calls.

For those so-called “discretionary” punishments, the disciplinary rate of black students was twice that of all other students. During the most recent data available, for the 2010-11 school year, there were 659,000 black students and 542,000 discretionary suspensions among them, but for all Texas public school students – 5 million of them – there were a total of 2.1 million discretionary suspensions. This trend was consistent for every school year from 2007-08 through 2010-11.

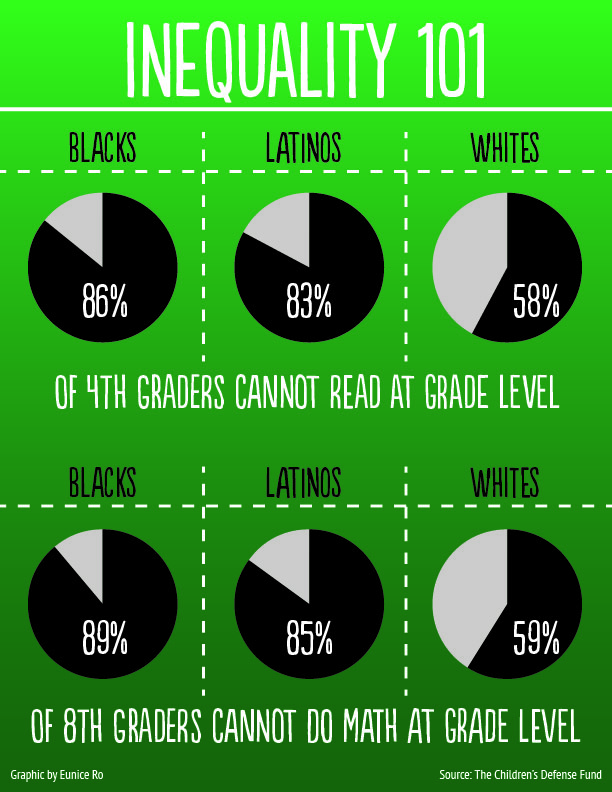

SOURCE: THE CHILDREN’S DEFENSE FUND GRAPHIC: EUNICE ROA way to tackle the question of race head-on must be found, said Skiba, who is a professor in counseling and educational psychology at Indiana University. He has concluded that “explicit attention to issues of race and culture may be necessary for sustained change in racial and ethnic disciplinary disparities.” He said it’s a difficult discussion to start with white teachers because they are uncomfortable talking about race. They will answer questions as though they are colorblind out of fear, he believes, of being labeled racist.

Something is wrong

The Texas study, released last July by The Council of State Governments Justice Center and the Public Policy Research Institute at Texas A&M University, found that black students were 31 percent more likely to receive discretionary punishments than white students. But, the study found, the racial mix of students who receive mandatory suspensions and expulsions is quite different. Mandatory punishments are few in number and prescribed by state law for the worst offenses, such as taking drugs or guns to school. In that catego

ry – where administrators are not allowed to exercise discretion – black students are 23 percent less likely to be suspended or expelled than white students.

The finding that black and white children are treated differently when school personnel make judgment calls, but not when punishments are automatic, smacks of racial bias. But the pivotal question of whether adults meting out the punishments are racially biased was not addressed in the Texas study.

Gregory, the lead author of the “Two Sides of the Same Coin” article, said no research has found that black students are more unruly than white students. “It’s not about higher rates of misbehavior,” she said in an interview.

The study of discipline in Texas schools also demonstrated that being suspended or expelled from class is often the first step on the path to dropping out of school.

Nationally, dropout rates for blacks are almost twice as high as for whites. Among young people who were age 16 through 24 in 2009 – the latest year available – 5.2 percent of white students had dropped out of school, compared with 9.3 percent of black students, according to the U.S. Department of Education.

What to do?

Encouraging more black men to teach as a way to ameliorate the racial disparities in discipline and achievement was an initiative discussed extensively at the Congressional Black Caucus Foundation’s annual legislative conference in Washington, D.C., last September. While he supports the idea, Toldson, the foundation’s research analyst, argues that it’s important to work with the teaching force as it is – 63 percent white female.

“I think there are a lot of positive aspects to increasing the number of black male teachers, but I don’t think that in and of itself is going to bring about the changes that we seek,” Toldson said during an interview later at his Washington office.

He and others advocate improving teachers’ “cultural awareness” to equip them better to relate to, and teach, black children. Toldson isn’t thinking of seminars or workshops for teachers. He prefers something more personal and direct.

Toldson, who has a doctorate in counseling psychology, believes teachers would make headway in the classroom if they invested time getting to know their students outside of school. Walking a student home occasionally could provide an informal setting for asking about students’ families, churches, their struggles, their reactions to the violence they see, their feelings about school.

“Sometimes we believe it’s harder to talk to the kids than it actually is,” said Toldson.

Gregory, of Rutgers, also has doubts about the effectiveness of lecturing teachers on cultural sensitivity.

“It’s not easy to do professional development, because people feel blamed, unfairly blamed,” she said.

Retired teacher Mike Charney, who worked as an American Federation of Teachers representative on issues of teacher expectations and raising black student achievement, said teachers must learn to be more fluid with kids who test them.

“Jumping to punishment as their first response to different ways of acting can lead to these disparities,” said Charney.

He said some teachers feel they’ve lost their authority and control of their classroom if – as an example – black students don’t take their seats as quickly as teachers would like. The issue becomes: Who is in charge? which escalates to sending students to the principal’s office. In his years as an inner-city Cleveland schoolteacher, Charney found that getting to know his students as individuals and learning about the successes in their lives, rather than dwelling on who was screwing up or challenging his authority, made all the difference in getting through to students.

Speaking for the National Association of Secondary School Principals, Judith Richardson, director of Diversity, Equity, and Urban Initiatives, said in schools where black students are punished more often, racial prejudice definitely plays a role, though she doesn’t believe the bias is deliberate.

“There’s always a bias in the system toward people who look like you. It’s because there is a comfort level,” said Richardson.

Educators agree something has gone wrong. Michael D. Thompson, director of The Council of State Governments Justice Center, said school leaders are keenly aware of the test score gap between black and white students and express concern that they are doing an inadequate job of educating African-American kids. “They are not in denial about it. They want to do better,” said Thompson.

But it may not be simple.

The schools that have effectively changed that equation are those that have improved school safety and the quality of the education for students on an individual level. “They don’t look at all kids. They look at each kid,” she said. Richardson makes the point that the answer is not to let standards for proper behavior slide. She said students crave safe, orderly schools. “You’re not going to have achievement until the discipline issue has become a non-issue.”

The Education Department’s Office for Civil Rights has been paying more attention to the issue of unfair disciplinary practices in schools during the past few years, opening 14 major investigations into school districts where statistics point to racially biased treatment. So far, the office is working with the schools and has not reached any conclusions as to whether there have been civil rights violations.

The civil rights office is also collecting more extensive data, and in a recently released report, another pattern emerged: The problems occur in suburban schools, too. The report contains data from three suburban counties that border the District of Columbia – Montgomery and Prince George’s counties in Maryland and Fairfax County, Va. – demonstrating that black students in those public school systems are more likely to be suspended than white students.

A better approach

It’s not that a simple suspension upends a child’s life. Often, it is what follows. Many school systems assign suspended students to alternative schools, such as Atlanta’s Forrest Hill Academy. Students say they rarely learn anything while in such schools, and are far behind when they return to regular classes, if they ever do. Some drop out, their solution to being disciplined at a school they simply aren’t interested in attending.

Terrell Townsend, 18, of Washington, D.C., is an example of the good things that can happen when a school works to capture a disaffected youth’s attention. Townsend was disciplined often throughout his school career in the District of Columbia’s largely failing school system.

He spent two years at Dunbar High School, which in the days before integration was the District’s premier school for black students. A new school building was built after desegregation, and it embraced the open school plan of the 1960s and 1970s – which proved to be a disaster.

When Townsend went there, the building had no doors or privacy for individual classrooms. Rooms were noisy. Partitions, or “fake walls,” as Townsend calls them, separated classes. Students took advantage of the building’s shortcomings.

“Books, chairs, all that would come over,” he said.

Just as disruptive were the false fire alarms that students triggered to force evacuations.

“It was wild in there,” Townsend said.

He often got into fights – over things as trivial as someone stepping on his shoe. It was only after he met one of the founders of a Washington charter school, named for poet and author Maya Angelou, and the man took a personal interest in him, that Townsend began to see school as fun.

The Maya Angelou founders – Yale University law professor James Forman, the son of the civil rights leader of the same name, and David Domenici, a lawyer and son of former U.S. Sen. Pete Domenici (R-N.M.) – are part of a new cadre of civil rights activists who see education as their new frontier.

For Townsend, his attention was piqued by dissecting a frog. Previously, in biology class, he had only been shown a film of a frog being dissected. When he finally was able to dissect his own frog, he was struck by the sensation of “touching the bones.”

“It was, point-blank, the experience,” he said. “That did it.”

At Maya, as the school is known, Townsend enjoys going to class. He likes the teachers. He likes being praised and recognized when he does well. Math, once difficult, became fun because his teacher, Heidi Simonsen, smiles and jokes with the kids. “She is just happy all the time,” said Townsend. Even if there’s something on his mind, he said it’s impossible to feel angry when she’s around.

During an interview at the school, Townsend was mostly guarded, until Domenici’s name came up. Then his faced opened into a huge smile. “I felt David Domenici was always one of those people in my corner.”

Domenici believes Townsend is college material and has been urging him to continue his schooling. Townsend is reticent to leave the comfort of his neighborhood, though he realizes the advantages of going to college.

Dream big

Maya Angelou isn’t the designated alternative school for suspended or expelled students in the District, but it is an alternative that reflects the ambitions of its founders to propel young people like Townsend to dream big.

Both men’s parents pushed for change that had enormous impact. Domenici’s father, when he was a senator, advocated successfully for changes in the way insurance companies cover mental health care. Forman’s parents organized civil rights workers in the South.

As hard-fought as those crusades were, fundamentally changing educational opportunities for black children sometimes feels harder, maybe even impossible. Forman and Domenici are among committed reformers who have vowed to overcome the institutional resistance and public indifference that has stalled progress.

“The three civil rights issues that I’m committed to work on [for the next generation] are better schools, less violence, and fewer prisoners. Those are my goals. Education is not the only way, but it is a key way to intervene on all three,” said Forman. “If you go to college, as a black man, you have taken yourself out of the prison game.”

Sandy Bergo is a Washington, D.C.-based writer who recently wrote about for-profit colleges for Youth Today.

This story was originially published in the June-July 2012 issue of Youth Today.