|

For more than 100 years, the emerald green 4-H clover has been a symbol of wholesome living. The National 4-H Council trumpets health as one of its “four H’s” and says its 6.5 million members pledge allegiance to a healthy lifestyle.

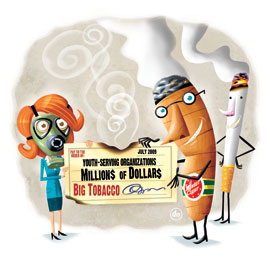

Over the past decade, however, the National 4-H Council has accepted more than $25 million from Philip Morris USA – maker of Marlboro, the best-selling U.S. cigarette brand and a long-time favorite of teen smokers.

That relationship illustrates an ironic pair of trends: While the federal government last month enacted more severe measures than ever to build a wall between tobacco companies and kids (see story, page 4), youth programs around the country are building bridges to those same companies.

The bridges are funded by tobacco company grants to help operate and study youth programs. Philip Morris USA, the largest U.S. tobacco manufacturer, says it has donated more than $230 million since 1998 to such organizations as Big Brothers Big Sisters of America, The Forum for Youth Investment and Boys & Girls Clubs of America.

Meanwhile, rival R.J. Reynolds Tobacco Co. (think: Camel and Winston) donates millions of dollars each year to such organizations as the YMCA, YWCA, Big Brothers Big Sisters, Boys Scouts of America, and dozens of universities and schools (including elementary schools).

Critics say youth organizations are sending the wrong message to their members and to the public by accepting money earned by tobacco product sales.

|

“Tobacco companies are simply not an appropriate source of funding for youth organizations,” said Paul G. Billings, a vice president of the American Lung Association. “The tobacco industry is looking for something in return for these donations, such as building their credibility and brand and improving their image. Tobacco companies are targeting kids for the next generation of replacement smokers. So youth organizations should not be looking to further the tobacco companies’ credibility.”

4-H CEO Donald T. Floyd Jr. vigorously defends the relationship with Philip Morris, saying the company has funded ground-breaking research on positive youth development and a health-focused program, dubbed Health Rocks, that includes an anti-tobacco component.

|

Also defending the practice is Judy Vredenburgh, the outgoing CEO of Big Brothers Big Sisters, which has received $22.5 million from Philip Morris over the past six years. “We’ll take money from anybody and everybody to fuel our growth plan and break the cycles of poverty,” Vredenburgh said. “We’re very happy to take money as long as there are no strings attached.”

Companies’ Motives

Philip Morris’ grant-making Youth Tobacco Prevention Department opened in 1998, the same year the company and four other U.S. tobacco manufacturers agreed to a $206 billion settlement to resolve health-related lawsuits filed by 46 states and several other jurisdictions.

Philip Morris USA spokesman William R. Phelps said the company began funding youth organizations that have anti-tobacco programs “because it’s the right thing to do. We believe that no kids should use tobacco.”

Later, Phelps suggested another reason: to keep critics off the company’s back.

“It’s important to point out that when kids smoke, that is bad for our business, because when kids use tobacco products our business feels pressure from many sources, and that can impact our ability to be successful,” he said. “And that pressure can be in the form of increased legislation that excessively restricts the sale or use or taxation of tobacco products. For example, excessive cigarette taxes impede our primary business goal, which is to compete for the largest share of the adult tobacco market.”

To some, the companies’ motives are enough reason to reject the money. Some of the state government agencies formed to disburse the money from the 1998 settlement refuse to make grants to organizations that accept funding directly from tobacco companies. Indiana’s agency imposed that condition after examining tobacco company documents that were unearthed during the litigation that led to the settlement.

“Those documents showed that the intention of the tobacco companies with their youth prevention materials and youth prevention media was really a public relations strategy and not a youth tobacco reduction strategy,” said Karla S. Sneegas, executive director of the Indiana Tobacco Prevention and Cessation Agency.

|

Sneegas said that conclusion is supported by a National Cancer Institute study released in June 2008, which reported that the tobacco industry’s youth anti-tobacco campaigns “have not worked.” The study also found that some adolescents are driven to start smoking by exposure to cigarette advertising, especially at convenience stores.

(Apart from its donations to youth organizations, Philip Morris and its parent, Altria Group, have spent millions of dollars on company-run campaigns designed to discourage kids from using cigarettes. In addition to Marlboro, some of the best-known Philip Morris cigarette brands include L&M, Chesterfield, Benson & Hedges and Virginia Slims. The tobacco company and anti-smoking groups have debated the effectiveness of those campaigns.)

“I would absolutely advise any institution that is interested in serving the true needs of young people to never accept funding from a tobacco company,” Sneegas said. “The intent of tobacco companies is to make money from generations of smokers. And the next generation of smokers is today’s teenagers.”

Some organizations, such as Indiana Black Expo, stopped accepting tobacco money so they could tap into the state grants, according to Sneegas. But she said others, such as Indiana University, have not applied for the state money because they want to continue to receive tobacco industry funding.

A Good Partner

Some youth organizations describe Philip Morris as an ideal partner that sets few conditions on its grantees, beyond promising to include the company’s name on their published donor lists.

|

“I can look myself in the mirror and know that taking money from Philip Morris is a pure thing,” said Vredenburgh of Big Brothers Big Sisters. The organization says it uses the money for its overall programming.

Kelly Williams, director of media and public relations for Big Brothers Big Sisters, said the decision to take tobacco money was a no-brainer. “The children we serve for the most part are from single-parent homes, kids who live in families that are on or below the poverty level, children who have parents who are incarcerated,” she said. “Do you think Philip Morris should be exempt from giving back to those communities and giving support to programs that get kids out of poverty?”

Karen Pittman, executive director of The Forum for Youth Investment, videotaped a testimonial for Philip Morris, which has donated $3.6 million to her Washington-based organization over the past four years. (Pittman is a columnist for Youth Today.) The forum uses the money for its main project, Ready by 21, which partners with organizations such as the United Way of America and the American Association of School Administrators to develop programs that prepare youths for college and work.

“Philip Morris has been an absolutely terrific partner from the beginning,” Pittman says on the video, which is posted on Philip Morris’ website. “They came and asked us what we were trying to do. They figured out ways to support what we were trying to do. ”

Referring to Philip Morris’ grant-making program, Pittman says on the video, “Positive youth development is critical to Phillip Morris’ business strategy as a company that sells adult products. Ultimately, the way to ensure that young people aren’t engaging in risky behaviors like smoking is to make sure that they really are productive. ”

National 4-H Council has similar praise for Philip Morris’ support of its Health Rocks program and its research into positive youth development. “There are only two things that Philip Morris required of us,” said 4-H CEO Floyd. “One was that we do [Health Rocks] excellent and, two, that we research it to make sure it worked.”

The 4-H Experience

Perhaps no group has gotten more flak for taking tobacco money than 4-H.

The council approached Philip Morris in the late 1990s to discuss the possibility of winning a grant. Floyd said that set off some “robust discussions” at the council’s headquarters in Chevy Chase, Md. “Some said: This is a good thing because they’re going to help kids. Some said: This is not a good thing,” Floyd said.

“We asked lots of questions” of Philip Morris executives, he said, and accepted the grants after being satisfied that “we would have independence [from Philip Morris] and that we would do things that are good for kids and make a difference.”

Floyd said assurances by a top Philip Morris official convinced him that the company’s charitable efforts are genuinely aimed at discouraging cigarette use by teens. “His point to us was: Look, we have an adult product and we’re going to do everything we can to keep kids from smoking,” Floyd said.

Campaign for Tobacco-Free Kids publicly scolded 4-H after it accepted its first Philip Morris grant, for $4.3 million in 1999.

“The National 4-H Council is an organization dedicated to youth development,” the campaign said then. “In contrast, Philip Morris is a company dedicated to marketing its deadly products to ensure the next generation of tobacco users.” The campaign called the partnership “another in a long line of public relations initiatives designed to give it [Philip Morris] legitimacy and avoid real change by making it appear reformed and responsible.”

Criticism also came from within 4-H. Tobacco-Free Kids reported at the time that 4-H groups in 27 states had opposed the tobacco company funding. Among those indicating that they wouldn’t participate: the 4-H state program leader in Wisconsin, California’s statewide 4-H advisory board, and the center for 4-H youth development at the University of Minnesota.

One of the biggest payoffs of the partnership, Floyd said, has been The 4-H Study of Positive Youth Development. The longitudinal study by Tufts University has tracked more than 6,000 youths in 41 states.

The study bills itself as the first to “show that the foundational characteristics of PYD [positive youth development] … can be measured, enabling youth development programs to prove their success.” It also finds that Health Rocks enrollees, who are said to be at higher risk for smoking than most youth, end up smoking at a similar or slightly lower level than the control group.

“Philip Morris should be given credit for doing the right thing in terms of funding independent, rigorous, empirical research about what more we need to do to promote health and positive development for kids,” said Richard M. Lerner, lead researcher on the study.

The Future

Speaking from Philip Morris headquarters in Richmond, Va., spokesman Phelps said the tobacco company understands it has a credibility problem among some youth organizations.

“Many question our commitment” to youth anti-smoking efforts, he said. “And we understand that skepticism.”

One question is whether the tobacco market will shrink when today’s participants in 4-H, Big Brothers Big Sisters and Boys & Girls Club come of age. Phelps said Philip Morris recognizes that its youth anti-smoking programs “may impact future sales,” but doesn’t seem concerned about those programs being so successful that they will significantly shrink the company’s market. “If you look at the United States, there are more than 40 million adults who smoke,” he said.

The most recent National Survey on Drug Use and Health found that among all age groups, 18- to 25-year-olds had the highest rate of tobacco use.

The survey, produced by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, found that among 12- to 17-year-olds, 3.1 million, or 12.4 percent of the population of that age group, had used a tobacco product in the month before the survey was taken in 2007. The survey found that cigarette and cigar use had declined among that age group between 2002 and 2007, and smokeless tobacco use increased.

As the debate continues, Pittman noted a fact that even vocal critics of tobacco company philanthropy cannot dispute. The products these companies sell “may be lethal,” she said, “but they’re legal.”

Also certain is that the companies consider their work with youth groups something to boast about. Altria CEO Michael E. Szymanczyk trumpeted the company’s youth philanthropy at his annual shareholders’ meeting in May: “We have continued our strong efforts to prevent underage use of tobacco. Our position is simple: Kids should not use any tobacco product.”

And, he said, “We continue to support organizations like 4-H, Big Brothers Big Sisters, and the Boys & Girls Clubs of America.”

Bill Brubaker is a Washington-based journalist and former staff writer for The Washington Post. Contact: brubakerDC@msn.com.