|

|

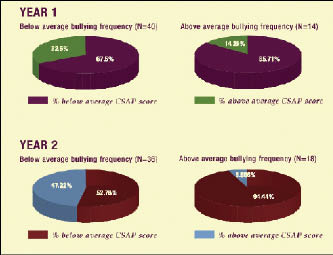

Source: The Colorado Trust. During the bullying prevention intervention, the gap in CSAP scores increased between schools with different levels of bullying. |

The Basics

The Colorado Trust gave the 45 grantees in its Bullying Prevention Initiative an average of $50,000 per year for three years to implement any program of their choice, as long as it had been shown to be successful. The two most widely used programs were Bully-Proofing Your School (used by at least 12 grantees), and the Olweus Bullying Prevention Program (used by at least seven grantees). Other programs included Second Step, Peace Builders, Promoting Alternative Thinking Strategies (PATHS) and Safe School Ambassadors.

The 45 grantees included 17 school districts; five schools; 23 community-based organizations, including an agency that manages four affordable housing properties, and local family- and youth-service agencies. Grantees met at least annually for training.

What They Looked For

This was not a program evaluation. Grantees implemented more than 20 different bullying prevention programs that used many strategies, including training youth and adults in conflict resolution, encouraging bystander intervention, developing skills on how to deal with bullies, creating a caring culture within a school and promoting an understanding of diversity.

The question posed by The Colorado Trust was two-pronged, said co-evaluator Kirk Williams: “ ‘Can you increase the willingness of youth to intervene – defined broadly – in bullying situations?’ and ‘Can you increase the willingness of adults to intervene and enhance their skills to implement bullying prevention programs effectively?’ ”

“They were interested – at the initiative level – in ‘Can we make a difference?’ ” he said. “Not in evaluating a particular program.”

Evaluators also examined the connection between bullying and overall school performance on the state’s standardized test, the Colorado Student Assessment Program (CSAP).

Methodology

Evaluators collected data from youth and adults each fall and spring during three academic years. Through focus groups and in-depth interviews, they asked parents and key site personnel – including teachers, youth workers, custodians, cafeteria workers and school bus drivers – about the successes and obstacles encountered during program implementation. They asked youths about their awareness of the bullying prevention initiative, and whether they perceived it as effective.

“There’s both a quantitative and qualitative component to this, which is invaluable,” Williams said.

At most sites, the respondents entered their answers into a Web-based electronic database; a small number completed paper surveys. The data were available immediately to the evaluators and to the grantees, who were trained to create useful reports from the database.

The youth surveys focused on the perception of bullying, the school climate and perceived peer support. For example, youths were asked whether they had “pushed, shoved, tripped, or picked fights with students I know are weaker than me,” whether school/site staff members were doing the right things to prevent bullying, and whether their peers cared about what happens to them.

School/site staffers were asked how likely it was that youth and staff members could be counted on to help stop specific bullying incidents, the degree to which bullying was a problem at their sites, and how often they had intervened to stop bullying.

For the 54 schools that participated in the initiative for all three years, evaluators analyzed CSAP scores to determine the percentages of students at each school scoring “proficient” or “advanced” on a combination of reading, writing and math tests during years one and two of the initiative.

What They Found

The evaluators found that, although bullying was prevalent at the sites during the first year of the evaluation, “the initiative had a positive impact over time,” according to Build Trust, End Bullying, Improve Learning, a report about the key findings.

• In year one, a majority of students in fifth through 11th grade reported experiencing some sort of bullying, although the frequency of bullying averaged only once or twice a year. Significant percentages of all the youths admitted bullying others verbally (57 percent), physically (33 percent) or online (10 percent).

• Bullying declined over the three-year evaluation period. Self-reported bullying of others dropped 12 percent, physical bullying decreased by 9 percent, and verbal bullying (which included online bullying) decreased by 5 percent.

• In year three, 95 percent of the adults surveyed said they believed it was their responsibility to intervene in bullying, and 60 percent identified bullying as one of the top five problems facing their school/site.

• Youths who felt a sense of belonging at school, believed they were treated fairly and with respect and believed their school was responsive to their needs were significantly less likely to report bullying others. They were also more likely to expect and seek an adult’s help with a bullying situation.

• Schools with lower levels of bullying had higher CSAP scores.

In year one, nearly 33 percent of schools with a below-average prevalence of bullying had CSAP scores above the state average, while only 14 percent of schools with a higher prevalence of bullying had above-average CSAP scores. In year two of the initiative, the gap increased: About 47 percent of schools with less bullying posted above-average scores, compared with only about 6 percent of schools with more bullying.

“What we suggest is that … a high prevalence or frequency of bullying interrupts the learning environment, and therefore you see these lower than average CSAP scores,” Williams said. “But,” he added, “the reverse could also be true. It could be that schools that have lower CSAP scores have a less caring and trusting context and maybe also have a culture that’s more tolerant, or even approving, of bullying.”