|

|

Youth at a TYC assessment unit. Photo: Michael Ainsworth/Dallas Morning News |

The most stunning aspect of the sex abuse scandal rocking the Texas juvenile corrections system is not the alleged abuse – the stories are sadly familiar – but how it went on even as youth workers kept sounding alarms.

The mess at the Texas Youth Commission (TYC) is, according to a report released by the commission last month, a startling lesson in administrative failure: A detention center security chief climbs a career ladder to the very top, even after someone finds pornography on his office computer; even after youth workers repeatedly complain about him taking boys from their dorm for private nighttime meetings; even after he quashes complaints about another administrator doing something similar; and even after someone claims to have found a nude picture of him on an Internet porn site.

These and other allegations became public in a big way last month, and now people have lost their jobs, the TYC board of directors has resigned, a grand jury is considering criminal charges, public hearings are exposing all types of abuse throughout the state system, and the state’s juvenile probation agency is feeling some aftershocks.

While the allegations in Texas seem especially outrageous, the systemic problems that they expose are not unique. “Texas, quite frankly, is a microcosm of what’s going on all over the country,” says Earl Dunlap, chief executive officer of the Richmond, Ky.-based National Partnership for Juvenile Services, a 1,000-member organization representing juvenile detention and correctional agencies.

|

|

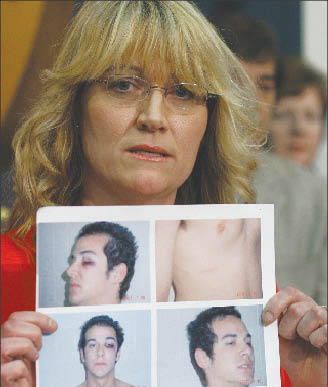

ABUSE CHARGES SPREAD: At a news conference last month, Genger Galloway holds up pictures of her 19-year-old son, whom she said was molested and beaten while in the care of the TYC. Photo: AP Images/Harry Cabluck |

That’s not to say it’s happening in all juvenile corrections facilities. But advocates say the misconduct against and among youth that does take place happens largely because of insufficient attention from administrators and policymakers and lack of independent oversight.

Scott Friedman, director of the Texas Juvenile Probation Commission’s (TJPC) field services division, says he hopes the scandal serves as a “swift kick in the pants” for the entire state.

“I’m actually very grateful for the attention, in a very perverse way,” he says. “Not much happens in juvenile justice without some kind of catalyst, and that’s been the history of our system nationally.”

For some juvenile justice advocates, the Texas case exposes a more fundamental problem. Dan Macallair, executive director of the San Francisco-based Center on Juvenile and Criminal Justice, says the juvenile detention systems in “two of the largest states are completely broken,” referring to Texas and California. “These old training schools have got to go.”

The Perils of Self-Regulation

|

|

Roy Brookins |

It’s difficult to know the extent of staff sexual assault on youth in state detention facilities. The U.S. Bureau of Justice Statistics (BJS) recorded 467 reports of abusive sexual contact by staff against youth in state-run juvenile facilities around the country in 2004, of which about 15 percent were substantiated. Texas had far more reports than any other state: 138, with 13 substantiated. Experts say that sexual assaults in corrections facilities, like such assaults in the general population, are vastly underreported.

After the scandal broke at the boys-only West Texas State School l

|

John Hernandez |

ast month, tales of abuse came pouring out of juvenile facilities throughout the state. On any given day, the TYC oversees more than 4,500 youth in residential programs – through 13 secure institutions, nine residential halfway house programs, and a half-dozen facilities operated by contractors. It also oversees 3,000 on parole. State investigators have been fanning out to those facilities to investigate additional complaints.

Following is a description of how the incidents unfolded, according to the internal report by the TYC’s general counsel, made public last month. (The report is at http://www.youthtoday.org/youthtoday, under News Links.)

Ray Brookins arrived at the West Texas school in October 2003 after serving as security director at another TYC facility, the San Saba State School. There he had been suspended for having pornography on his office computer and was accused by staff of regularly taking youth into his office at night with the blinds closed. Administrators told him to “only counsel one-on-one in his office when absolutely necessary and to have his blinds open when doing so,” the report says.

How did he get hired at West Texas? The school’s superintendent, Lemuel Harrison, said he didn’t look at Brookins’ personnel file at the time. The warning about meeting boys alone doesn’t appear to have made it into that file anyway.

That points to a significant administrative vulnerability in many juvenile justice systems: self-regulation. The systems tend to be more reactive than proactive and are reluctant to police themselves, Dunlap says. “In most states and in most jurisdictions,” he says, “it’s the fox that guards the henhouse.”

When problems are handled internally, administrators decide which allegations about staff members to put in someone’s file. They are often reluctant to take that step unless they’ve got concrete evidence, like pornography on a computer.

Warning Signs

Within 60 days of Brookins’ start at West Texas, staffers started telling administrators that he was “taking youth off dorms in the evenings, alone,” according to the TYC report. When asked about the behavior, Brookins explained that he was just talking to the kids.

Then he was promoted to assistant superintendent – making him the boss of staffers who might complain about him.

From then on, the report says, “the number of incidents of Mr. Brookins being seen alone with youth after hours increased, and the number of staff noticing the behavior grew.” Employees also claimed that the school principal, John Hernandez, was taking boys alone to classrooms at night.

When complaints about the two men reached Harrison, he told them “to stop being alone with youth to clean buildings after hours,” the report says. When he subsequently heard more reports about Hernandez, Harrison told the principal to keep the classroom doors ajar.

Hernandez has publicly denied any wrongdoing.

If any of the allegations against the two men are true, then in retrospect, their actions seem obvious from the outside. But official denial of the obvious is a common thread running through prison sexual assault cases, says Jennifer Haymes, senior counsel on the National Prison Rape Elimination Commission.

The commission, established in 2004 by the Prison Rape Elimination Act, investigates the impact of sexual violence at adult and juvenile correctional facilities around the country. It held a hearing in Texas late last month.

“One of the factors that triggers this is a level of denial,” says Haymes. “A lot of systems out there … believe that this is not a problem, so therefore [they say] there’s nothing special that we need to do about it.”

Dunlap says federal and state politicians and policymakers – more than staff – shoulder the blame for neglecting the “forgotten group” of the 50,000 or so youth confined on any given day in the United States. “Kids in detention and corrections just don’t pull a lot of weight with our policymakers,” he says.

Disconnect from Staff

Analyses of administrative breakdowns often reveal that top administrators became disconnected from concerns of staff on the front lines – a sure way to miss a simmering problem. Even after Superintendent Harrison issued warnings to the two men at West Texas, accusations against them grew.

“The community of employees working behind the fence was abuzz with rumors, speculation and innuendo” about the two men, the former director of clinical services, Robert Freeman, later told investigators.

The administrative response illustrates the minefield for staff and supervisors trying to grapple with sex abuse allegations. After abuse is uncovered at an institution, investigators typically find early accusations that were so vague or open to interpretation that managers didn’t pursue them formally or threw up their hands because they couldn’t determine the truth.

However, more and more organizations have policies to automatically send all such complaints up a chain of command, creating a paper trail and a formal inquiry by people who are not close to the parties involved.

Those problems played out in West Texas. Eventually, a caseworker wrote an e-mail to a supervisor about a boy’s claim that Brookins touched him inappropriately. The supervisor decided that “the contact was not offensive and could not be reported further,” the report says.

When a formal inquiry did kick in – spurred by Brookins allegedly watching a boy in a shower and calling him a “stud” – witnesses “contradicted one another and the conduct that did occur was open to interpretation,” the report says. Brookins was cleared.

In October 2004, Harrison took an extended medical leave, and Brookins became acting superintendent.

Silence

While sex abuse is an especially difficult crime to uncover – largely because the incidents usually occur in private and the victims are reluctant to talk – several common elements in juvenile justice facilities make the investigations even harder.

Alison Parker, an attorney for Human Rights Watch programs in the United States, says the lack of independent oversight of facilities can create an atmosphere ripe for abuse. That is particularly true at institutions that house kids in locations far from their families, legal counselors or other guardians. The West Texas State School sits on a 52-acre facility in rural Pyote.

A 2006 Human Rights Watch/American Civil Liberties Union investigation of remote female juvenile facilities operated by New York state uncovered inappropriate and excessive force, as well as sexual abuse and harassment by staff. Girls feared that if they complained, the staff would know about it, Parker says.

In addition, she says, “there wasn’t a state agency really charged with following up on those accusations, visiting the facility and ensuring that the people responsible were held accountable,” which is the “primary problem with certain aspects of the juvenile system.”

Such intimidation can silence kids and adults alike. In Texas, the TYC report says the youths allegedly abused by Brookins and Hernandez “were apparently influenced to remain silent by the control the two had over their length of stay and services that could be provided after release. Non-victim youths did not report for fear of retaliation from Mr. Brookins. Staff did not report their suspicions for fear of retaliation by Mr. Brookins.”

In fact, when a specific complaint about Hernandez abusing a boy reached Brookins in late 2004, Brookins told the administrator who forwarded the claim “not to tell anyone else about the report, to not even talk to her supervisor about it again,” according to the TYC report. “That report ended with Mr. Brookins.”

Answers, Anyone?

When an agency is having severe internal troubles, staff behavior can be the canary in the coal mine. In early 2005, some West Texas administrators noticed that a lot of staffers were resigning, according to the TYC report, and that workers’ compensation claims and use of force with the youth at the facility were both increasing. The exiting staff often complained about how Brookins and Hernandez were running the facility.

Then, in February 2005, a volunteer at West Texas contacted the Texas Rangers, about an allegation of sex abuse by staffers there. The rangers, who are an investigative division of the Texas Department of Public Safety, started an investigation that day.

The news media sporadically reported on the West Texas situation in 2005; then the story picked up steam in February, when some news organizations – especially The Texas Observer – started putting the disparate pieces together. The national media jumped on the bandwagon.

The rangers’ investigation concluded that the men had engaged in sex acts with boys at the facility. Both men have resigned, but no charges were filed.

Now reforms are under way throughout the Texas juvenile justice system. The governor appointed a special master to run the system, and a hotline has logged more than 1,000 calls alleging abuse and other mistreatment.

But what about other systems throughout the country? Here are some ideas:

• Dunlap, of the National Partnership for Juvenile Services, says youth need ways to report complaints to independent investigative units. The situation in California, where an independent inspector general oversees the Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation (including state-run juvenile detention centers), illustrates how difficult it is to establish a system for anonymous reporting of sexual abuse.

California’s chief deputy inspector general, Brett H. Morgan, says that although posters in juvenile corrections facilities tell youth to write or call his office with complaints, the youths know that staff can open their mail and listen to their phone calls. “That’s something that bothers me, that we get so few” sexual abuse complaints, he says.

• Macallair, of the Center on Juvenile and Criminal Justice, says a consensus is emerging among state policymakers that such abuse allegations stem from a fundamental problem: shipping youth offenders off to large state institutions. Macallair calls these facilities relics of the 19th century reform school system, and says they should be eliminated in favor of community-based services.

• Parker at Human Rights Watch says Texas should appoint an independent ombudsman to ensure that abuse investigations aren’t stonewalled.

For now, juvenile justice advocates remain frustrated. “It’s absolute and complete nonsense,” Dunlap says, “that in the year 2007, we do not have adequate mechanisms in place that prohibit or minimize the opportunity for these kinds of things to happen.”

Contact: TYC (512) 424-6130, http://www.tyc.state.tx.us/index.html; testimony from the field hearings of the National Prison Rape Elimination Commission, http://www.nprec.us/proceedings.htm; the Human Rights Watch report, http://hrw.org/reports/2006/us0906/index.htm.