|

You start working with kids as a single 20-something, full of passion for making a difference. By your mid-30s, many of you go looking for careers that will pay the mortgage.

Those of you who stay in the youth field tend to change jobs a lot, because it’s the best way to move up.

As many as half of you work part-time, and a lot prefer it that way.

Two-thirds of you have a college degree.

Too many of you work without health insurance.

You lament that youth work is not adequately respected as a profession.

You are the American youth worker. And now, a century after paid youth work gained a foothold here, researchers are getting a more complete picture of who you are: your motives, your working conditions, your wishes and your frustrations.

Youth workers have always been hard to define, just like youth work itself. Over the past several years, however, a series of studies has produced unprecedented information about the work force – information that should help employers keep good workers, and help advocates improve the field.

“It’s a big mish-mash of people playing in this field,” says Ellen Gannett, director of the National Institute on Out-of-School Time. “To get a handle on who they are is a little bit challenging. I think we’re getting closer.”

The biggest recent step involves two studies based on surveys of more than 5,000 youth workers and released late last year. Conducted by the Next Generation Youth Work Coalition and the National Afterschool Association, with funding from Cornerstones for Kids, the studies “offer the clearest picture to date of what the youth work profession looks like,” the Next Generation report says.

The studies do not claim to be nationally representative samples. The Next Generation study is based on responses from 1,053 youth workers and 195 program directors in eight communities. The NAA survey involves 4,346 workers, covering every state. Each study included focus group discussions.

|

Here are some of the findings, with comments from youth workers gathered by phone and e-mail.

Age

No surprise: The field is dominated by young adults. Half of those surveyed for Next Generation were under 30, and one-third were under 25. Thirteen percent were under 22. The NAA survey found that about one-third of the workers were under 30.

That youthfulness is particularly striking when compared with teachers, 4 percent of whom are under 25, according to Next Generation. The report notes that “the youthfulness of the work force more closely resembles occupations like waiting tables … than it does other social services professions.”

|

Dion Maltbia, 30, has been in and out of youth work since his teens and is now director of teen services for the Thornberry Unit at the Boys & Girls Clubs of Greater Kansas City. Although he likes youth work, he says, “There’s no way you could live off the salaries, unless I moved up the ladder or started trying to become a president or CEO of a whole organization.” His objective, he says, is to continue working directly with young people, probably through his own business.

In San Francisco, Vicky Valentine says 64 percent of the staff at her agency, Health Initiatives for Youth, are under 30. In fact, the health educator writes, “I’m creeping close to 30 myself and feel that I’d like to step down from youth education soon to make room for a young person. … I honestly feel that even with the best training and intentions, that adults cannot educate youth as well as trained members of their own peer group can.”

|

In the same city, 32-year-old Meredith Laban plans to stick around – she’s director of Summerbridge San Francisco, an academic enrichment program – but she sees why so many people leave the field by the time they’re her age. “If you have been doing youth work since you were 22 and hit 30, you might be burned out, need more money, or move into more senior roles and no longer work directly with youth,” she writes.

Next Generation found that another wave of workers seems to enter in their 40s and 50s. It seems likely that they tired of their first careers or rejoined the work force after raising children.

Education and Experience

In both surveys, most of the workers had college degrees. For example, the NAA found that 67 percent had at least a two-year degree, and 55.2 percent had a bachelor’s degree or higher.

However, the NAA found that the degrees were often only marginally related to after-school work, such as early childhood education, recreation and counseling, or were in general disciplines, such as business administration and sociology. One reason, the study notes: “There are few degree programs with content specific to the afterschool field.”

Such educational backgrounds are typical of youth workers in general. Laban majored in Peace Studies. At the New England Network for Child, Youth & Family Services, training director Cindy Carraway-Wilson says she majored in psychology, “with my master’s focusing on existential psychology.”

But “while I did not plan to be a ‘youth worker,’ ” she writes, “I knew I wanted to work with young people in some capacity.”

Others entered youth work as a way to pursue other objectives, such

as broader community change. Michael Chavez, a youth care coordinator with Hogares, a residential treatment center in Albuquerque, N.M., majored in community planning and plans to pursue as master’s degree in architecture. “I’ve never taken an actual class in specific youth work,” he says.

Next Generation did find that two-thirds of the respondents had specific “credentials or certificates related to their work,” such as a youth work or teaching certificate.

The findings reflect the reality that employers, by and large, hire people with educational backgrounds that seem somewhat relevant, then train them in youth work. At the Wayne Finger Lakes BOCES, a job training program in Waterloo, N.Y., youth development services coordinator Rebecca Ahouse writes, “Adults with professionalized positive youth development credentials are the proverbial needle in the haystack.”

As for previous work experience, Next Generation found that 42 percent of those surveyed had worked in education, while 40 percent had been in child care and 24 percent in social services. The staff at Alternatives, a youth development nonprofit in Hampton, Va., reflects those diverse experiences. Executive Director Kathryn W. Johnson writes that her staff’s backgrounds include education, ministry, social work, community organizing and volunteerism.

Why Are They Here?

We know youth workers aren’t in it for the money. “Putting Youth Work on the Map” found plenty of support for a long-held belief about youth worker motivation: “People who do youth work want to make a difference, and feeling like they are doing so is a critical factor in influencing whether they remain in the field.”

After-school workers cited working with children as their primary motivation, but when the NAA asked after-school workers what would make them stay in the field, 71 percent indicated “an opportunity to make a difference.”

That’s the case for Courtney Klein, executive director of Youth Re-Action Corps, in Tempe, Ariz.. She plans to stay in nonprofit community work, although maybe not always in youth work, because “it’s a mix of both wanting to belong to a great cause and at the same time have the freedom to work in a new way. To not step into a position eight to five, and do the conventional thing.”

Chavez, however, again shows another way that people enter the field. The youth care coordinator with Hogares says he got his first job, working with youth with autism and physical disabilities, when “I just saw an ad in the paper. My mom said, ‘You’re 16, you can start working now.’”

Where Do They Work?

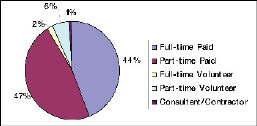

Next Generation found that its survey respondents were employed primarily in three organizational settings: independent community-based organizations (30 percent), local affiliates of national organizations (29 percent) and school-based programs (24 percent).

How Often Do They Work?

One of the most significant findings in Next Generation is that half of the respondents said they work only part-time in the youth field, and many of them are happy about it. For NAA, about 40 percent said they work part-time.

Next Generation notes that “the average percentage of part-time employment across industries is 20 percent.” It says part-timers make up about 25 percent of child care workers and 40 percent of food services employees.

For years, youth work observers considered the large part-time work force to be one of the field’s problems. “Everybody used to say the reason we have so much turnover is because we have so many part-time workers,” says Gannett of the National Institute on Out-of-School Time. “I’ve been guilty, too. …. If we could only make these jobs full-time, people would stick around.”

Next Generation found that part-timers reported “extremely high levels of job satisfaction,” equal to that of full-time workers. While 60 percent are interested in full-time work, it’s surprising that so many are not.

One reason they like the part-time work is flexibility in their hours. Also, many work at other jobs that pay more, or have other interests they want to pursue. Fifty-three percent of the part-timers held second jobs, the report says.

For instance, Maltbia of the Boys & Girls Clubs in Kansas City took some time off from the field a few years ago to pursue interests in music, writing and financial management, then returned part-time for a while so he could continue those pursuits.

For many after-school programs, of course, part-time positions are inherent; most of the programs don’t run all day. The NAA found this to be more of a challenge. Compared with full-timers, the report says, the part-timers are less educated and don’t get employment benefits. “These workers are most likely to have frequent turnover, and while they enjoy working with children and youth, they think of afterschool as a great job, not a profession,” the report notes.

Next Generation suggests embracing this work force reality as a benefit, with agencies focusing more on how to recruit, train and keep part-timers.

For example, Next Generation found that 80 percent of full-time workers had access to health insurance, compared with only 5 percent of part-time workers. Some agencies, such as Alternatives, offer employment benefits to part-timers on a pro-rated basis. It helps to retain staff, even as they reach their 30s and 40s, says Executive Director Johnson.

“The majority of our work is conducted in the afternoon hours at multiple sites,” she writes. “Maintaining a staff that includes part-time workers is critical.”

Pay and Benefits

Despite their motivation to help kids, workers contacted for Next Generation cited pay as the top factor in their decision to stay in or leave the field.

The survey found a median salary range of $25,000 to $25,999, and a median hourly wage range of $9 to $10.99.

(The 2005 youth ministry salary survey by Group Magazine reported an average “salary package” of $39,049.)

The NAA found that 21.8 percent of respondents do not receive any employee benefits.

The low pay and thin benefits contribute to turnover in the field. In a summary of the Next Generation and NAA surveys, Next Generation says the findings “suggest that many consider youth work viable until developmental milestones, like raising a family and owning a home, become priorities. When those in the NAA study who plan to leave the field were asked why, two of the top reasons were to seek better wages and benefits elsewhere.”

Consider Michael Heathfield, a veteran youth worker from the United Kingdom who for years has been director of certification programs and training services at the Chicago Area Project. He recently left to teach full-time at Harold Washington College and to coordinate social work activities.

“I hit 50 and I thought, ‘I need a better pension than my community organization is ever going to manage,’ ” he says.

From Job to Job

So youth workers quit a lot.

Among the Next Generation respondents, 36 percent had been at their current organizations for a year or less; 22 percent had stuck around for at least five years.

“Data from program directors point to an annual turnover rate of roughly 30 percent,” Next Generation says. It says the turnover rate among teachers is about 15 percent.

Leaving their jobs doesn’t always mean leaving youth work, however. More than half of the workers in the Next Generation survey said they’d been in the field five or more years, “suggesting the work force is at least somewhat experienced.”

But those who stay in the field find that they must move around among employers to move up. Fewer than half of those surveyed for Next Generation said there are “clear opportunities for promotion” within their organizations. “This finding, combined with the length of service pattern, suggests that workers may be forced to create their own career ladders, moving around within the field in order to increase earnings or take on new roles,” the report says.

Laura LaCroix-Dalluhn sees the pattern as executive director of Youth Community Connections, a partnership organization based in Minneapolis. “We see youth workers moving to organizations with greater capacities and larger budgets as a means of moving up the career ladder,” she says.

“If you want to keep working directly with youth your best shot is always one of the really large organizations,” such as a YMCA, says Delroy Calhoun, director of the Loring Nichollet-Bethlehem Community Center in Minneapolis. “They have a longer career ladder right there within the organization.”

At small organizations like his, he says, “There’s no place for them to go.”

Training

Continuing education and training are considered major benefits by many youth workers, but the opportunities and rewards vary widely.

Next Generation found that almost eight in 10 youth workers had attended training in the previous six months, while just 5 percent said they’ve never attended training.

This wasn’t as true in after-school programs specifically. NAA reported that “many workers seem to lack training opportunities once employed in afterschool, and this problem contributes to staff turnover.”

While the agencies usually pay the training fees, the percentage is not enormous – 62 percent do so, according to Next Generation – and only one-fifth of those surveyed said their organization “formally recognizes or rewards participation” in training.

In other words, training isn’t usually tied into raises, bonuses or promotions.

Typifying the approach is the Loring Nichollet-Bethlehem Community Center, which director Calhoun says provides full-timers in youth employment and tutoring with about $1,500 a year for continuing education. But that education doesn’t bring more pay. “We’re hoping that with more training, they’ll be better at the job they have here,” Calhoun says.

Cash-strapped agencies that pay for training don’t feel they can also afford to raise salaries for people who attend the training. It’s understandable, not only because of the extra money, but because it’s difficult to demonstrate that a worker who comes back from training is immediately a more financially valuable employee. The benefits of continuing education are usually subtle.

Thus, getting employers to link training to pay “has always been a little bit of a barrier,” Gannett says. “The employers haven’t fully bought into it.”

That, however, impedes efforts to get workers to attend training, says Mark Levine, director of the Center for After-School Excellence at The After School Corp., in New York. “You’re asking people who may have multiple jobs, single parents, to give up their Saturdays for a year or two,” he says. Then “they’re making the same salary with the same title and the same duties, with no clear reward.”

Going Legit

Perhaps the subject on which youth workers and administrators agree most passionately is the need to boost the status of the field.

“Youth work is still considered to be ‘glorified babysitting’ to many outside of the profession, writes Carraway-Wilson of the New England Network for Child, Youth & Family Services.

“The field is invisible,” writes Johnson at Alternatives. “I participate on our region’s work force development committee. Routinely, there are discussions regarding the need for systems change in order to better meet the needs of young people. However, the only groups that are mentioned are business, government and schools. The youth-serving sector is nonexistentin the conversation.”

To Heathfield, the former United Kingdom youth worker, youth work has the same reputation in the United States that it did in the United Kingdom 20 years ago. “Nobody had any idea of what a youth worker was,” he says. In the United States today, “There isn’t a public consciousness about what the youth workers are and what they do.”

All Charts for this article are from Next Generation Youth Coalition.