LOS ANGELES — When it comes to treating HIV/AIDS in Southern California, there’s arguably no hospital more involved in the fight than Children’s Hospital Los Angeles. The man leading Children’s Hospital’s charge against the disease, Dr. Marvin Belzer, is one of the most respected HIV specialists in the state.

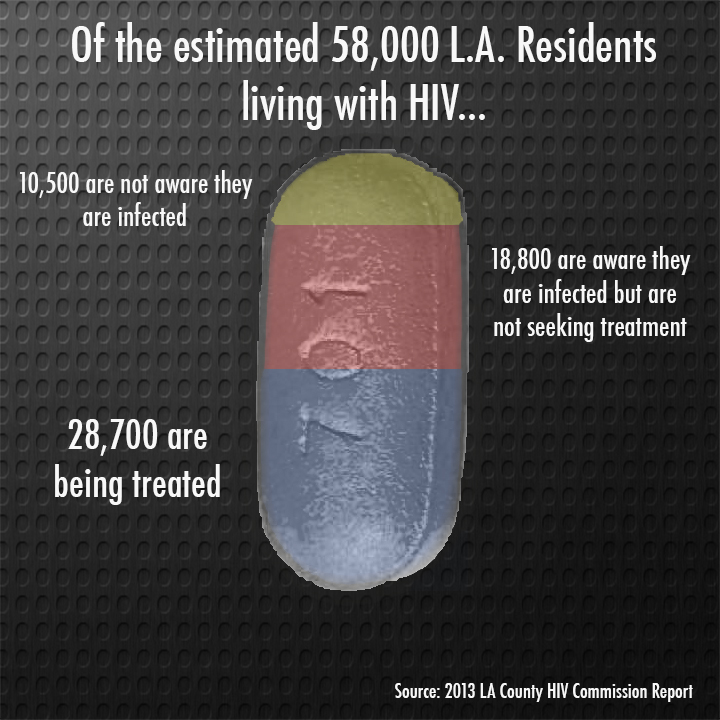

Belzer sees a wide range of teens with HIV as head of the hospital’s risk reduction program. The program offers free care to LGBTQ teens at risk contracting HIV and AIDS and specializes in care for transgender teens who have contracted the disease. The clinic also provides service to teens in at-risk communities who have difficulty getting care due to social determinates such as lack of health care, accessibility to hospitals or low income. With more than 58,000 HIV positive people estimated by the Los Angeles County Department of Health to be living within county lines, there’s never a slow day.

Belzer sees a wide range of teens with HIV as head of the hospital’s risk reduction program. The program offers free care to LGBTQ teens at risk contracting HIV and AIDS and specializes in care for transgender teens who have contracted the disease. The clinic also provides service to teens in at-risk communities who have difficulty getting care due to social determinates such as lack of health care, accessibility to hospitals or low income. With more than 58,000 HIV positive people estimated by the Los Angeles County Department of Health to be living within county lines, there’s never a slow day.

At the height of the AIDS epidemic in the ’80s and early ’90s, more than 2,000 people were dying of the disease per year. Now, that number has dropped below 400, and thanks to advances in treatment, more and more infected people are able to live full and healthy lives.

But on a day-to-day basis, Belzer notices a worrying consistency in the majority of his patients: “About 50 percent of the patients we get are Latino males,” he said. “Then another 35 to 40 percent are African-American [males]. In Los Angeles, they combine to make about 20 or 25 percent of the total population, so the disparity is very clear.”

Beyond Los Angeles, the disparity between population and infection rate becomes even starker. According to a recent study from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, approximately two-thirds of all new HIV diagnoses among teens in 2013 were from African-Americans, despite the fact that they make up only 15 percent of the nation’s teen population. In Los Angeles, African-Americans make up approximately 10 percent of the total teen population. In addition, more than 90 percent of all new teen male infections in 2011 were caused by gay intercourse.

In fact, Belzer says infection rates among gay teens has risen in the last three years, though the number of women infected and cases caused by infected needles has decreased. One of the main reasons, he explains, is because it is harder for doctors to convince these young men to come in for treatment due to obstacles that are far more social than medical.

“A lot of the teens we see have problems that compound on each other,” he said. “They have a history of trauma, social stigma and substance abuse. They’re afraid to come in to us because they are afraid that their family and friends will ostracize them.”

It is this fear of rejection that has led to a category of HIV cases that doctors are making a top priority to address: those who are aware they are infected but do not adhere to treatment. According to a 2013 report by the LA County Health Department (LACHD), there are an estimated 1,700 people between ages 13-24 in this category, along with another estimated 350 teens who are HIV positive but do not know it.

The LACHD report also includes plans to address the different categories of HIV targets, ranging from HIV negative but high-risk patients to patients already in care. To prevent further infection, the report recommends additional opt-out screenings at school clinics and juvenile detention centers, as well as focused condom distribution in areas where HIV infections are frequent.

The most important new weapon in the prevention arsenal, however, is the pre-exposure prophylaxis pill (PrEP). Doctors are encouraging people in at-risk areas and demographics to use the pill daily to help drastically reduce the chances of infection.

The most important new weapon in the prevention arsenal, however, is the pre-exposure prophylaxis pill (PrEP). Doctors are encouraging people in at-risk areas and demographics to use the pill daily to help drastically reduce the chances of infection.

“PrEP is a prescription pill, and to get it, you have to document that you don’t have HIV, but you may be at risk because of your behavior. Either you have unprotected sex or you have protected sex with someone infected,” said Dr. Mark Katz, regional HIV/AIDS advisor for Kaiser Permanente of Southern California. Katz has been involved in HIV treatment since the start of the epidemic and helped start Kaiser’s first HIV clinic at their West LA Medical Center in 1988.

“PrEP prescriptions are also given out with follow-up screenings every three months, so if you take the pill, you have to come back to make sure that the treatment is doing its job,” Katz said.

Meanwhile, HIV clinics like that of Children’s Hospital offer services that cast a wide net over not only HIV treatment, but the social and physical problems often associated with it. The actual treatment of HIV is simpler than ever. The days of the three-pill “drug cocktail” used by the likes of Magic Johnson 20 years ago are gone.

Drug companies have combined the three drugs that counteract the virus into a single retroviral pill. If taken daily, this pill reduces the number of viruses in the body so drastically that the threat of infection is drastically reduced. While they go through the process, patients at clinics like Belzer’s get access to resources that help them prepare for life with HIV.

“We have counseling to help them discuss HIV and have referrals to social programs that can help them with school supplies or transportation,” Belzer said. “We want to create an environment where these teens feel comfortable tackling this problem and getting their lives back together in the process.”

This combination of condom distribution, increased testing and whole-person care is called the “treatment cascade.” Since the National HIV/AIDS Initiative was launched by President Barack Obama in 2010, the cascade has been adopted nationwide as the primary strategy for getting as many HIV patients diagnosed and virally suppressed as possible.

But while all the new developments in treatment have made taking care of the disease easier than ever and greatly reduced the threat of infection, Katz worries that the one-pill solutions are causing young people who are infected or in environments that put them at risk of infection to let their guard down and ignore safe sex practices. Katz still feels that HIV education should be a top priority.

“Back in the ’80s, a lot of young people, particularly young gay people, were so vigilant because so many of them had lost friends to AIDS,” he said. “Now, knowing that HIV is so treatable and that medication is making infection less likely, there are many young people who aren’t following safe sex guidelines. We are still seeing lots of young people get infected, so we need to continue educating young people and reminding them that PrEP is not a substitute for being responsible and practicing safe sex.”

LACHD’s goal is to get half the HIV positive population on regular retroviral treatment and reduce the number of new infections by 25 percent by the end of 2017. In addition, the National HIV/AIDS Initiative aims to increase the number of MSM (males having sex with males) patients with full viral suppression by 20 percent, particularly among African-Americans and Latinos.

So far, both programs are on track to reach these goals, but with the state health care system in transition due to the Affordable Care Act and the Medi-Cal expansion, there’s still debate over how funds should be distributed. Included in the LACHD report are plans to reduce funding for outpatient care. County officials believe that with more patients insured through the Affordable Care Act, the funding for outpatient care can be focused toward services not covered by insurance.

On Feb. 10, Los Angeles County cut $4 million from contracts with private HIV/AIDS care providers. At the Board of Supervisors meeting where the budget cut was approved, dozens of activists from the AIDS Healthcare Foundation protested the move, saying that outpatient funding was still needed to help those who have not yet received treatment.

Where these freed-up funds will go has not been fully determined — LACHD declined requests for comment — but one possibility could be services like Belzer’s clinic, which provided whole-person care. As the average lifespan of people living with HIV expands, that could be the new model of future treatment.

“HIV is no longer necessarily a death sentence, but it does become a part of the lives of those who get it,” Belzer said. “Usually, those who don’t know how to deal with it have other health problems that stack on top. When we treat someone with HIV, we’re doing more than just giving them pills and telling them what to do with it. We’re helping them prepare to live full, healthy lives.”

Back to main story “Epidemic of HIV Among Youth Needs Structural Repair, Experts Believe”