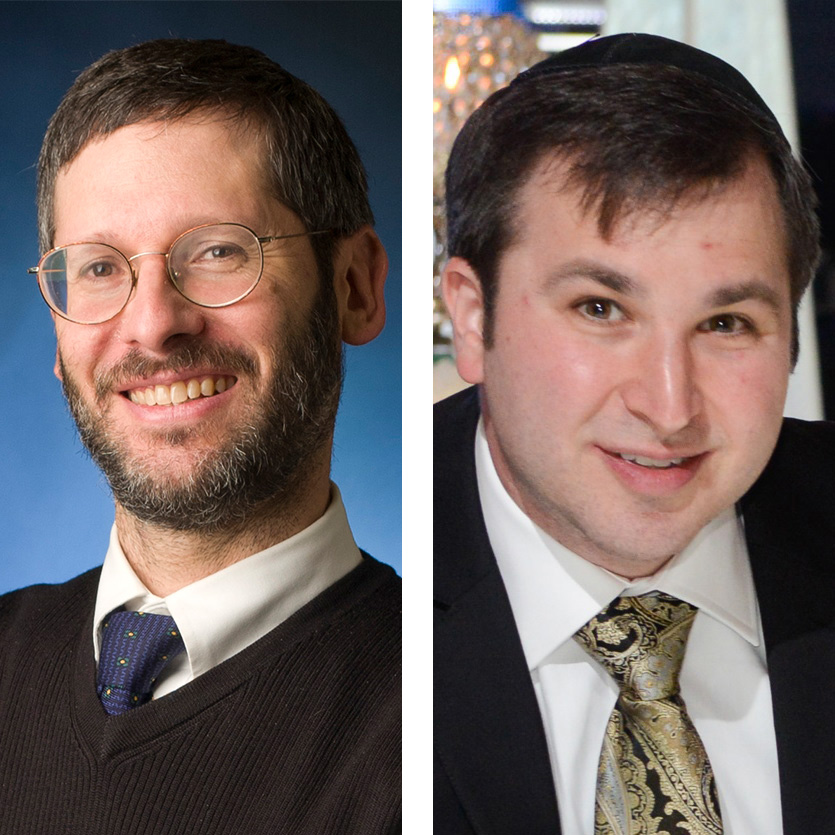

Daniel Pollack

Jonathan Lerner

Like most parents, my good friend and his wife are concerned about their child’s future. They know they need to prepare her to be on her own one day.

My friends are also scared. Not because he recently had a near-fatal heart attack. Their fear is more deep-rooted. Their 13-year-old daughter has Down syndrome and they are apprehensive about her future.

Specifically, they are worried that one day, some unscrupulous person will take advantage of her sexually. This fear is not far-fetched. According to an article in Journal of Family Violence, among the developmentally disabled, as many as 83 percent of the females and 32 percent of the males are victims of sexual assault. Adolescents and young adults are particularly vulnerable.

Government policy mandates a shift from institution-based care to specialized care provided within the community, where persons with developmental disabilities may have the opportunity to live independently in the least restrictive setting. Toward this end, state-supported services are meant to help families and relatives continue to care for their developmentally disabled loved one. In addition, states provide home-like settings and care for developmentally disabled individuals who do not live with their families.

The community is seen as a natural setting that builds on existing supports and social networks, helping to promote inclusion. In fact, states frequently contract with private providers to support individuals with complex behavioral and medical needs.

Transitioning developmentally disabled people from institutions to the community has been an excellent choice for some people. For others it is a noble cause only in theory.

In reality, have we put in place sufficient oversight and support to care for this vulnerable population in the community? Monitoring the safety of developmentally disabled individuals living in the community is extraordinarily challenging.

How often are states mandated to visit developmentally disabled individuals? What is the nature of such visits? Do visits provide the state with a genuine look at a person’s living conditions or are service providers able to quickly give the appearance of safety and cleanliness in advance of a scheduled visit?

Unfortunately, there is little uniformity in the monitoring policy across states and many of them require only minimal supervision. For instance, California requires multiple home visits per year, some of which must be unannounced. Illinois only requires that the state check on its licensed community living arrangements once every three years. No unannounced visits are required.

My friends would be happy if their state’s policy called for frequent unannounced visits so that everyone near their daughter would constantly be on their best behavior. That is why many parents of developmentally disabled individuals in Illinois support HB3451, introduced in February 2015, which proposes to make licenses for community living arrangements valid for only one year and to require unannounced site visits to ensure compliance with the appropriate standard of care.

My friends would like to feel confident that their daughter’s home in the community will be safe and free from predators. Like the parents of many children with developmental disabilities, they would like to know that the state will watch over their child long after they are gone.

Daniel Pollack, MSSA, J.D., is a professor at the School of Social Work, Yeshiva University in New York City, and a frequent expert witness in cases involving child welfare and developmental disabilities. Jonathan G. Lerner is a licensed attorney in New York and Connecticut.