Video: Roger Newton

SANTA FE, New Mexico — Mauricio Lopez-Marquez hadn’t wanted to be carted from Mexico City to Santa Fe when he was an undocumented 14-year-old. His parents talked about the amazing opportunity he and his brother Gustavo would have. But Mauricio felt isolated in this strange new place. He didn’t want to learn English. He didn’t want to go to high school. He didn’t want to fit into life in this strange new place. And so he didn’t.

“One night I left out of the window to meet with friends and was going to go break into cars,” said Lopez-Marquez, who was 17 at the time. “We got caught and the police asked for our parents’ number.”

“One night I left out of the window to meet with friends and was going to go break into cars,” said Lopez-Marquez, who was 17 at the time. “We got caught and the police asked for our parents’ number.”

When his mother came to pick him up, she told him firmly this was the last chance he had to stay in the United States. If he was deported, his parents wouldn’t try to get him back. He’d be on his own.

Lopez-Marquez, now 28, said the threat of being separated from his parents pushed him to focus on creating a life in New Mexico. And part of creating that new life was channeling his teenage angst into helping other young Latinos who were struggling with the isolation and aimlessness he’d faced. Getting into the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals program when he was 18 helped him turn that calling into a reality as a social worker.

“As soon as I got a Social Security number, I knew I would get a license and practice,” he said. Through DACA he was also able to get in-state college tuition at New Mexico Highlands University, where he got his bachelor’s and master’s degrees in social work.

Mauricio Lopez-Marquez has dinner with his parents at his home. They are his ultimate supporters.

Photos: Roger Newton

Today, Lopez-Marquez is at Presbyterian Medical Services, Santa Fe Family Wellness Center, where he’s the only male social worker on staff who’s also bilingual. He is also an after-school folklorico dance instructor for Aspen Santa Fe Ballet. Between counseling and dance, Lopez-Marquez works with 180 youth in New Mexico; his work permit through DACA makes all that possible.

But now the program, which protects about 690,000 undocumented immigrants brought here as children, is in a state of flux, and because of that, Lopez-Marquez’s jobs are too.

DACA was officially rescinded by President Donald Trump in September 2017, with renewals allowed until Oct. 5. Renewals have since been reinstated after a court order issued Jan. 9 while a lawsuit challenging the decision to end the program moves forward.

It’s still unclear what legal effect the judge’s ruling will have. The Justice Department could appeal the injunction, and President Trump came out publicly against it, saying that it’s up to Congress to find a solution for Dreamers.

Congress has been in gridlock as progressives refuse to give up ground on immigration rights and conservatives push back on security issues. With both sides unable or unwilling to compromise for now, the Dreamers are faced with an uncertain future as the clock ticks toward March 6 — the program’s expiration date.

While some political groups have painted the so-called Dreamers as selfish — taking jobs and opportunities away from native-born citizens — many like Lopez-Marquez are focused on giving back to youth in their communities, doing everything from social work to mentoring.

“For me it’s been really hard to know that this could end at some point and with that a lot of my dreams,” Lopez-Marquez said. “A lot of the things that I’ve been working on for 10 to 15 years now.”

Effect on youth of Lopez-Marquez leaving

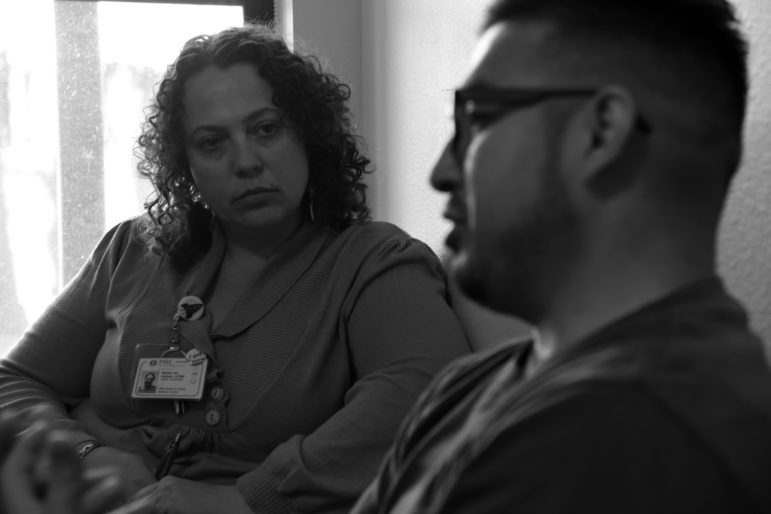

As a social worker, Lopez-Marquez’s precarious immigration status gives him a unique perspective. He can connect to many of his clients and their families who have been going through similar struggles since Trump was elected president.

“I tell my families that I’m a DACA recipient — a lot of families are in the same boat,” he said. “When they know I’m in the same boat, they can talk about certain things.”

Santa Fe is about 47 percent Latino. Because Lopez-Marquez is one of the few caseworkers who is bilingual, 99 percent of his caseload is made up of Spanish speakers. They and their families have varying immigration statuses and struggles, and Lopez-Marquez has had to facilitate some difficult conversations that hit close to home for him.

“One of my clients said, ‘My parents will be deported,’” Lopez-Marquez said, recalling a difficult session he’d had with a client who was afraid that if his parents were deported they would leave him in the country alone. “And I said, ‘What does that mean?’ I had to bring in their parents. At the end of the conversation, they came away with the understanding that they’d [all] be together no matter what.”

Lopez-Marquez is glad when he can facilitate such conversations to bring family members’ fears out in the open and connect them with resources to address those fears. He said there’s been a lot of fear and misinformation in the immigration community since Trump took office.

Samia van Hattum, a community health educator who works at the same health center, said Lopez-Marquez can provide better service to his clients because he is the only male bilingual counselor there.

His precarious immigration status isn’t the only thing that differentiates him from the rest of his co-workers. Samia van Hattum, a community health educator who works at the same health center, said Lopez-Marquez can provide better service to his clients because he is the only male bilingual counselor in the center.

“Males who are Spanish-speaking are like unicorns” in community mental health, van Hattum said. “The entire family can communicate with him. It’s often boys who need male role models, and don’t get that because there are not enough to go around.”

From what she’s seen, bilingual counselors in community health are rare because the need is so great for them that they often go into private practice where they can make more money. The few male counselors in the profession are fast-tracked into administrative roles, she said.

“In his role, he offers a unique ability to connect with people in a way that no one else can. That would be removed if he’s gone,” van Hattum said.

Luis Lagunas, 13, leads young dancers in a folklórico performance. He dances for the Aspen Santa Fe Ballet and is mentored by Lopez-Marquez.

Claudia Perez’s son Luis Lagunas, 13, was Lopez-Marquez’s client for two years and is now a dancer in his dance troupe. She said if Lopez-Marquez were to lose his DACA status it would negatively affect the whole community.

“Not only does Mauricio work with my son but he works with other people inside of a clinic,” she said. “I’m worried about the people at the clinic who might have needed his guidance because he’s bilingual.”

Perez said she went through three counselors for her hyperactive son before finally finding Lopez-Marquez, who could communicate with the whole family.

Lopez-Marquez would combine talking to Luis with games and walks in the park to help him use up his intense energy. He helped Luis manage his hyperactivity in school and focus better.

“He helped me focus with ADHD. We played games and he told me each time that he wanted to see my grades and if I did good I could play more games. It helped me stay motivated,” Luis said.

Perez has two other children: Samuel Alberto, 17, a Dreamer, and Maria Vanessa, 15, who was born in this country. Luis is the only of her children who had behavioral and speech issues, Perez said. Lopez-Marquez gave her the support she needed to advocate for her son’s special needs in a foreign country and in a language that was not her own.

“Having a therapist who spoke English and Spanish made it easier for the family to understand hyperactivity and how it affects someone’s grades and behavior. It wasn’t just him trying to be annoying,” Perez said.

But maybe the most important thing Lopez-Marquez did for Luis was introduce him to folklorico, which helped him channel his energy into something that became a passion.

When Luis dances, any hint of hyperactivity goes away. He is transformed from a kid with a short attention span into a dancer with a laserlike concentration. He keeps the beat with about 10 others, adorned in a bright blue and white headdress, shaking red maracas.

“It’s really fun to dance and I like trying my best to be better than the others,” he said. “I want to be the best one there. It keeps me motivated to keep trying hard.”

Perez said dancing is the one thing that motivates her son to keep his grades up. He knows his grades can’t go below average or he’ll be kicked off the dance troupe.

“If it hadn’t been for Mauricio we wouldn’t know how creative Luis could be,” Perez said. “I realized that he was good at the arts and we needed someone like Mauricio, who also likes the arts and recognized that to foster it — without that, I don’t know where my son would be today.”

And Lopez-Marquez’s DACA situation is even more personal for this family. Perez’s older son Samuel Alberto got a Davis New Mexico scholarship, which gives him a full ride to attend the University of Denver in Colorado. He wants to be a doctor, but with DACA up in the air, his future is too.

Luis doesn’t like to talk about DACA and what might happen to Lopez-Marquez or his brother. But when prodded, he approaches his brother’s immigration problem with the sweet innocence of a 13-year-old trying to comprehend impossible complexity and the power it holds over someone he loves.

“We can probably fix the papers. If he doesn’t get a chance to go to college or get a job,” Luis said thoughtfully — in case the papers can’t be fixed — “he can live with me because I have papers.”

A young folklórico dancer has her headdress adjusted prior to a performance.

Through the uncertainty of his situation, Lopez-Marquez continues to work 70 hours a week — two full-time jobs. He’s impossible to catch between counseling in the clinic, practicing in the afternoons and shows at various churches during the evenings. There he crams into a room with the 100 or so dancers and doles out costumes, sets up the dances and stays behind to help clean it up. His father is often there in the background fixing costumes for the troupe — his parents are his ultimate supporters.

“A lot of my kids know I have DACA. When Trump came out [and abolished the program in September] I told them, ‘Look, you know I might not be here next year,’” Lopez-Marquez said. “We’re just taking it one day at a time.”

Allegra Love is an attorney and director of the Santa Fe Dreamers Project, which gives free legal advice and advocates for Dreamers in Santa Fe. She said people like Lopez-Marquez, a friend of hers, are essential to build up a successful community. And it isn’t in the state’s best interest to lose them.

Especially in a state like New Mexico, which is consistently one of the poorest states in the country. Its rate of population growth has been almost completely stagnant at 1.1 percent from 2010 to 2016. What’s more, it is losing professionals between the ages of 40 and 54 along with children ages 5 to 19. Love says ending DACA and removing its 7,000 recipients would only exacerbate those dire conditions and lead to other serious economic ramifications.

The Center for American Progress estimated the cost to each state’s gross domestic product if DACA recipients were not counted. It estimates it would cost New Mexico $384 million a year, which is roughly .45 percent of New Mexico’s GDP of $93.6 billion, according to the U.S. Department of Commerce’s Bureau of Economic Analysis.

If anything, Love says they should be doing everything they can to keep people like Lopez-Marquez, who are able to help the community and the economy.

“I am certain that if he went to Mexico he would thrive there. But we want him here. We have a shot at this kid and we want to keep him,” Love said.

Read More of Our Dreamer Coverage