Would you invite elected officials to visit your youth program? Would you welcome the prospect or shake in your shoes at the idea?

Earlier this year, as federal funding for after-school programs appeared in peril, after-school leaders took action.

Some visited their members of Congress in Washington. A few invited elected officials to visit their programs. Some may be hosting officials at Lights On Afterschool, a day celebrating after-school programs, which is Oct. 26 this year.

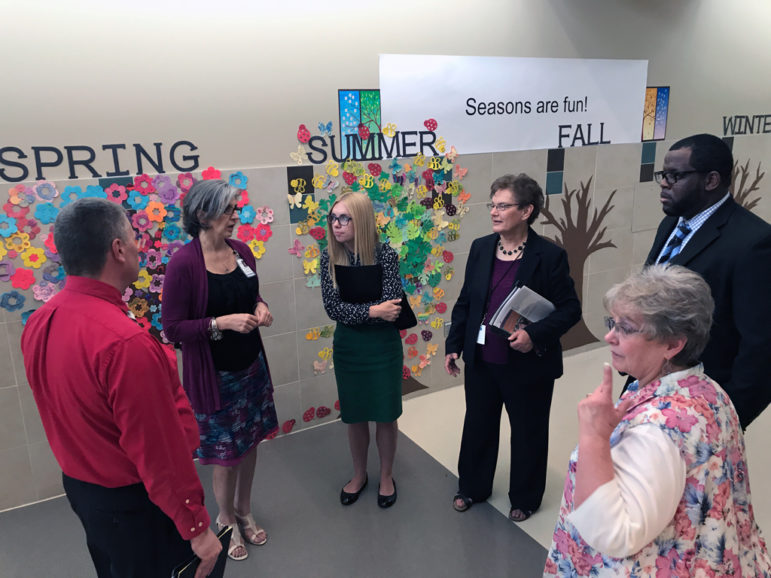

Community Education Partnership is a nonprofit after-school provider in Utah that invited two members of Congress to tour its program this year. CEP serves 6,000 children in 23 schools in West Valley City, a city of about 140,000. Nineteen of those schools have programs funded with federal 21st Century Community Learning Centers grants.

“The most important thing is to work with someone at a city council level who knows elected representatives in your district,” said Margaret Peterson, CEP executive director. It’s easier to make contact that way, and “it saves time if they know who you are,” she said.

Her organization invited Utah Republican Sen. Orrin Hatch to come in June. Peterson had served 20 years on the West Valley City Council and already knew Hatch, a longtime supporter of after-school programs. Although he did not come in person, he sent a staff member, Jessa Reed, who was very attentive and interested in the program, Peterson said.

Reed spent more than four hours touring after-school sites, including an internet safety presentation for junior high students and the high school program for kids with special needs.

Peterson provided Reed a chart of six years of teacher surveys showing outcomes for kids who attended the after-school program.

“In every single measure [including behavior and academic performance] we saw a 20 percent to 60 percent improvement,” Peterson said. “It was new information to her.”

Peterson’s goal was to show the importance of after-school and “the good that can happen,” she said.

CEP also hosted Laurel Price from the office of Utah Republican Rep. Mia Love in April.

Don’t be daunted

“Calling your elected officials can seem kind of daunting,” said Marcel Braithwaite, director of community engagement for the Police Athletic League of New York City. The nonprofit organization reaches 35,000 youngsters with its teen clubs and after-school, sports and early learning programs.

Braithwaite said to start with the assumption that your organization — and you as a citizen — should have a relationship with your elected officials.

“Our agency has a concerted effort to have one person focus on engaging with elected officials,” he said. “We’ve just learned over time that having a relationship that is ongoing and established is better than coming to them when it’s a crisis.”

Be persistent because they have a lot on their calendar, he advised.

Braithwaite suggested contacting the official’s office at least a month in advance.

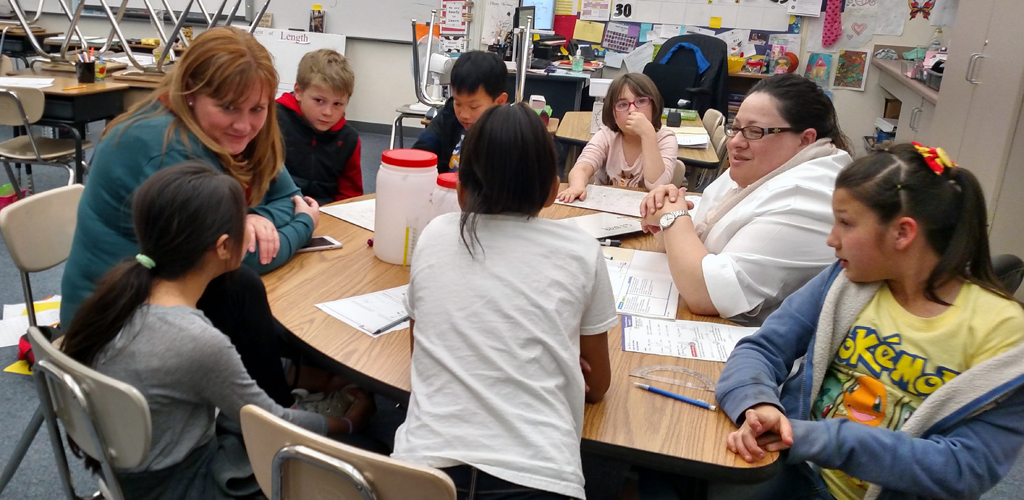

The Community Education Partnership after-school program in West Valley City, Utah, recently hosted Jessa Reed (third from left), a representative from the office of Republican Sen. Orrin Hatch of Utah. The organization provided her with fact sheets and other information in the five hours she spent touring three schools.

“Take the time to follow up,” he said. After the initial email or mailed invitation, make a phone call. Follow that up in writing and then check back by phone.

In July, PAL kicked off its summer PlayStreets program with the ceremonial opening of a fire hydrant in Harlem. Among the guests were New York City Council Speaker Melissa Mark-Viverito and a representative from the office of Rep. Jose Serrano, D-New York.

Braithwaite said the best way to host an elected official is to have an event.

“It showcases the best of what your agency does,” he said.

He advised having a clear idea of what you want from the experience.

Also think about how your after-school program leaders and youth can be involved in a project the elected official is championing, he said.

“It’s not just a one-way street,” he said.

The Afterschool Alliance has extensive advice on how to host a site visit, including advice on communicating with the official, prepping your staff, creating fact sheets and organizing the tour.

Getting political?

But how cosy should nonprofits be with elected officials?

Stand for your mission, advises the National Council of Nonprofits.

“Advocacy is really about always focusing on the mission,” said Rick Cohen,

director of communications and operations for the council. “Every nonprofit has a mission. At the end of the day, it’s not about sustaining the organization, it’s about the people the organization serves.”

Advocacy is much broader than reaching out to elected officials, but it includes establishing a relationship with them, he said.

“The best thing is to establish a relationship as early as possible,” he said. Invite members of Congress to visit during their recess, he suggested. “It’s a way for them to understand the real impact of budget cuts or other changes in legislation.

“Invite them often,” Cohen said. Keep them or their key staff members aware of your organization and the work it does, and reach out to city officials and state legislators as well as members of Congress, he said.

A role for students

In April, adults and students in the after-school program at Bain Middle School in Cranston, Rhode Island, hosted Democratic Rep. Jim Langevin of Rhode Island.

The before- and after-school program at Bain is funded through 21st Century, and leaders were concerned about threatened loss of funding in President Donald Trump’s “skinny budget.”

Kids, including some high school students who had formerly been in the program, took on a big role in showing the congressman around, according to an article in the Cranston Herald newspaper.

Student Avery Hart showed him a greenhouse students were assembling that would be topped with solar panels, students discussed a NASA competition they were involved in, and one said she relied on the academic help she got after school, according to the newspaper.

“[Without the program] I’m 100 percent sure I’d still be in the eighth grade,” Sujiere Payano said, according to the Herald.

Langevin wrote on his website that students in the school’s Youth Empowerment Zone told him they’ve established a strong leadership team: “This program is immensely important to these students.”

He pledged to protect funding for after-school programs because the students “deserve every opportunity to better themselves, their education and their future,” he wrote.