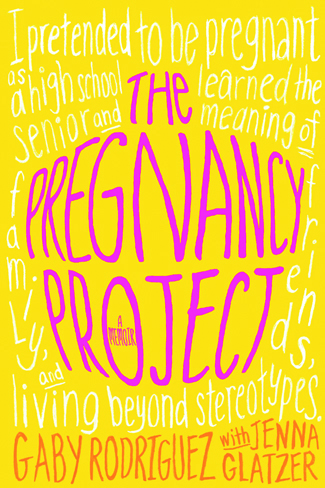

THE PREGNANCY PROJECT: A MEMOIR

Gaby Rodriguez with Jenna Glatzer

Simon & Schuster

218 pages

“I’m The Girl Who Faked Her Own Pregnancy as a Senior Project,” declares Gaby Rodriguez on the opening page of this story behind the 2011 headlines from Yakima, Wash., which became a 2012 Lifetime movie.

Gaby’s “superhero” mother, Juana, became pregnant at age 14 with Gaby’s oldest sister, Nievitas, and married the baby’s father, who was from Mexico. After 16 years of marriage, Juana’s abusive husband sued for divorce, forcing her to leave. Juana was allowed to see her three girls and four boys just once a week. When their father deserted them, Juana gathered her children in her brother’s crowded house, working overnight factory shifts to support them. After she briefly dated an immigrant farm worker, Gaby was the result. Today, Gaby writes, her mother is “the center of my world.”

At age 9, Gaby took care of her 16-year-old sister’s baby – Jessica was the fifth of Gaby’s seven siblings to have a child out of wedlock. With 31 nieces and nephews, Gaby wondered why teenage parenthood seemed contagious.

In a lilac gown at her Quinceañera – a 15-year-old Latina’s first step toward womanhood – Gaby processed into church on her mother’s arm. Her oldest brother, Genaro, promised to play the father’s role as her partner in the last dance but left after getting obnoxiously drunk. Although Gaby didn’t expect to see her father, who had another family, he turned up just in time for her dance. Genaro never apologized. It was “a sad turning point in my life,” writes Gaby, realizing that Genaro continued his drunken father’s legacy.

An excellent student, Gaby was determined to go to college. For her senior project, she wanted to “make a dent” in the problems she saw around her in Toppenish, Wash. Its population of 9,000 is more than 75 percent Latino. Almost 98 percent of its students get free or reduced-price school lunches. One-third are learning to speak English, and many come from migrant families. The one-in-five who drop out of school often cite pregnancy as the reason.

Studying human reproduction in biology, Gaby had a brainstorm: She could fake a pregnancy for her project. Not only would it help her understand her family and the teen moms at school, it would also explore stereotypes and statistics. Why is the likelihood of becoming a teen mother three times higher for the daughters of teen mothers? “I’ve been told for so long that I was going to end up just like my sister Jessica,” writes Gaby. “If I gave people what they wanted, how would they react?”

Gaby broached her idea to Mr. Greene, the school principal. She would need the help of these confederates: her boyfriend Jorge as the baby’s father, her mother, her sister Sonya and her friend Saida. Their reports of others’ reactions to Gaby’s pregnancy would reveal influences on teen mothers to keep, abort or give up their babies. Only a few trusted adults could know about the project, which would fail if word got out.

Overjoyed to receive approval, Gaby found a project mentor, who taught classes for expectant mothers. “This is going to be very big,” her mother predicted. In November, Gaby mentioned her late period to a friend. Saida dropped public hints about Gaby’s nausea.

Gaby hadn’t realized how difficult it would be to lie when telling her teachers she was pregnant. She cried when her science teacher seemed worried about the prospects of one of his finest students. When her spies reported that students were saying “she’s ruined her life,” Gaby wondered if teen mothers’ “grim statistics” result from “the limits other people project on them.”

Christmas felt “like a funeral” as her family ignored Gaby and Jorge. Her mother and Sonya reported her brothers’ nasty comments. Jorge’s parents wouldn’t speak to him for a week, and his friends kept saying he was trapped. Why do people “throw teen parents under the bus,” Gaby wondered, when what they need is support? Debuting “the bump” that Gaby’s mother made with half a basketball, wire, clay, and cotton batting, Gaby noticed that people looked at it first, before her face. Her belly was “a badge of shame.”

Gaby’s account of this marathon experience becomes a page-turner. We share her suspense as Gaby faces the “Big Reveal” in April. When she gives her presentation for 800 students plus teachers and staff, how will they react to being duped? Would the girls who really were pregnant realize she was “honestly trying to give them a voice?”

During Gaby’s finale, audience members read aloud the anonymous comments that people had made behind her back. When she yanked off her fake belly, shocked gasps preceded a standing ovation. The newspaper reporter who interviewed Gaby afterward said, “This is going to be big.” Yakima’s front-page story was picked up by the Associated Press, leading to Gaby’s interview for local television’s evening news. The next day, reporters from four networks turned up at Gaby’s school.

The resulting international media frenzy was heroically handled by Mr. Greene until the school district found an attorney, who engaged a literary agent and writer to help Gaby tell her story. She savored her exciting trip to New York with Juana, Jorge, Saida and Mr. Greene for TV interviews on NBC’s “Today Show” and Telemundo. Retaining her good sense and modesty, Gaby explained that she plans to use funds from her book and film for college and a new car for her mother. “My biggest hope going forward,” she writes, is “to spread the messages of my project,” advocating for teenage mothers as well as middle-school sex education. This courageous young woman never loses sight of her values, nor does she hide the angst of a teenager responding to the challenges that her experiment provokes. Such humility and compassion could change the world.

Contacts: TEEN.SimonandSchuster.com; mylifetime.com

Cathi Dunn McRae, former editor of Voices of Youth Advocates, specializes in teen writing and reading.