NEW YORK — After 18 days on a bus to the Mexican city of Reynosa, five days walking through the desert to Texas and two months living in Long Island, the fate of 18-year-old Axel Caballero of Honduras rested in the hands of an immigration judge who hovered above him inside a federal immigration courtroom in downtown Manhattan.

He sat in silence on the morning of Feb. 23 as the judge read the details of his case in a language he had only begun to learn. A lawyer for U.S. Customs and Immigration Enforcement jotted down notes a few feet away from the teen as he waited for a court-appointed interpreter to tell him what was going on.

The judge had three minutes to decide what to do with Axel, who had wanted to escape the violence, poverty and corruption that afflicted his native country. To the immigration authorities, he was just another migrant from Central America who violated immigration law when he set foot into Texas in December, alongside 17 other Central American teens.

The judge had three minutes to decide what to do with Axel, who had wanted to escape the violence, poverty and corruption that afflicted his native country. To the immigration authorities, he was just another migrant from Central America who violated immigration law when he set foot into Texas in December, alongside 17 other Central American teens.

“Now everything is going to be different,” Caballero said to himself at the time.

A few other teenagers waited in the courtroom for their turn before the judge. Almost 150 more appeared in court that same day as Caballero. Whether they arrived recently from Honduras, Guatemala or El Salvador, they all wanted the same thing — to avoid deportation back to the dangers of their home countries.

Mercy from the U.S. legal system could make the difference between living a peaceful life in the United States or facing death from the notorious gangs who control the streets in many Central American cities like Progreso, Honduras — Caballero’s hometown.

“Basically young people live in fear there,” Caballero said in Spanish. “You go out into the street and they kill you.”

[Related: Children Will Continue to Flee Danger, Expert Says]

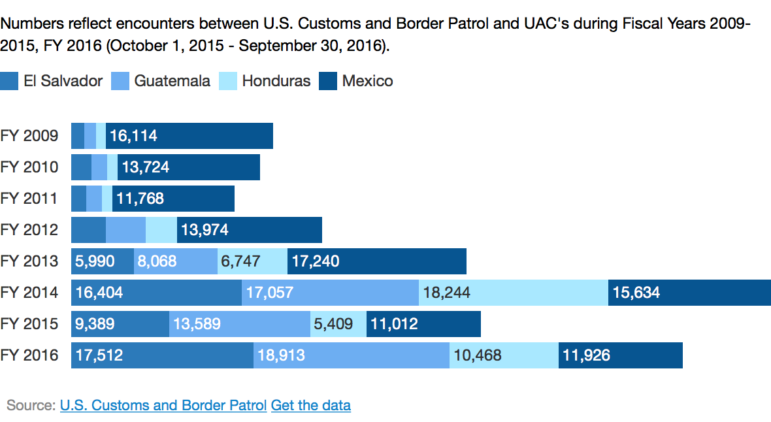

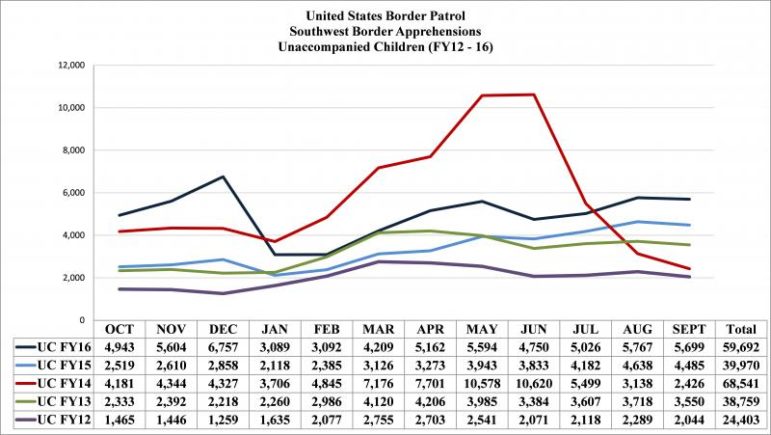

Approximately 150,000 other unaccompanied minors, people under age 21, have hoped to escape such a fate in the past three years by turning themselves over to immigration authorities after crossing the U.S. border with Mexico. The Obama administration allowed the majority of them to stay with relatives while their cases made their way through overwhelmed immigration courts. But that could change under President Donald Trump.

The vast majority of the children could qualify for political asylum given the dangers of returning them to their home countries, according to the Safe Passage Project, a nonprofit that represents migrant teens in immigration court. That could also change under President Trump, who has already begun implementing a crackdown on illegal immigration. Proposed changes in immigration policy, leaked to the news media last week, indicate that Trump and Homeland Security Secretary John Kelly might go after parents who tell their children to make the dangerous journey across the border with only a predatory coyote to guide them through the hunger, heat and cold.

The leaked memos suggest that the administration could strip protections from teenagers like Caballero who reunited with a parent in the U.S., major media outlets reported.

But Caballero had no way to navigate such legal nuance on Feb. 23. He had no lawyer to guide him. All he could do was answer the judge’s questions and hope for the best. She asked him where he lived, whether he went to school and who took care of him.

Then the judge told him her decision. Like the dozens of teens who came before and after him, Caballero would receive the gift of more time. He has until January 2018 to find an attorney and prepare his case, otherwise he will have to face an ICE attorney alone.

The U.S. government does not provide free legal representation in immigration court because it is a civil rather than a criminal process. Luckily for Caballero and other teenagers who appeared in immigration court that day, a woman in the back of the courtroom could help them find some pro bono legal representation.

She was among a team of lawyers from the Safe Passage Project. In recent years, thousands of Central American teens have avoided deportation with the help of New York City lawyers who volunteer for the nonprofit based out of New York Law School’s Justice Action Center.

“Without it, it is almost impossible for kids to assert their rights,” said Deputy Executive Director Gui Stampur.

In his experience, about 80 percent of unaccompanied minors qualify outright for immigration relief under U.S. law, he said. Those who do not still have legal recourse through Obama administration policies that deprioritized the deportation of teens who came to the U.S. illegally but have not committed any crimes.

The Trump administration has sent mixed signals about its intentions toward juveniles who crossed the border without their parents. The leaked memos suggest that protections given to “unaccompanied” minors would only apply to those without a parent in the U.S.

That would mean the administration could detain children who cross the border or even criminally prosecute their parents. New barriers to political asylum for children escaping violence in Central America would hit home for Caballero and his mother, who works as a cook in Westbury, New York.

Three siblings remain in Progreso; his mother wants to send for them as soon as she saves enough money. They, too, would have to ride a bus for 18 hours and cross the desert that straddles the U.S.-Mexican border.

They too would think of nothing but hunger, cold and heat for days on end until they reached Texas. But new policies could deprive them of the same happy ending their big brother Axel received two months ago, when immigration authorities put him on a plane to New York City after he turned himself in. His mother greeted him at the airport and said the three words she had not been able to tell him in person for years.

“She said that she loved me,” Caballero said.

Alejandra O’Connell-Domenech contributed to this report.