One’s kicking himself over an unrequited lifelong crush.

One dreams of being a Navy SEAL.

Another leads you on a mocking tour of his new home.

They’d seem like typical teenage boys — if they weren’t awaiting trial for violent crimes.

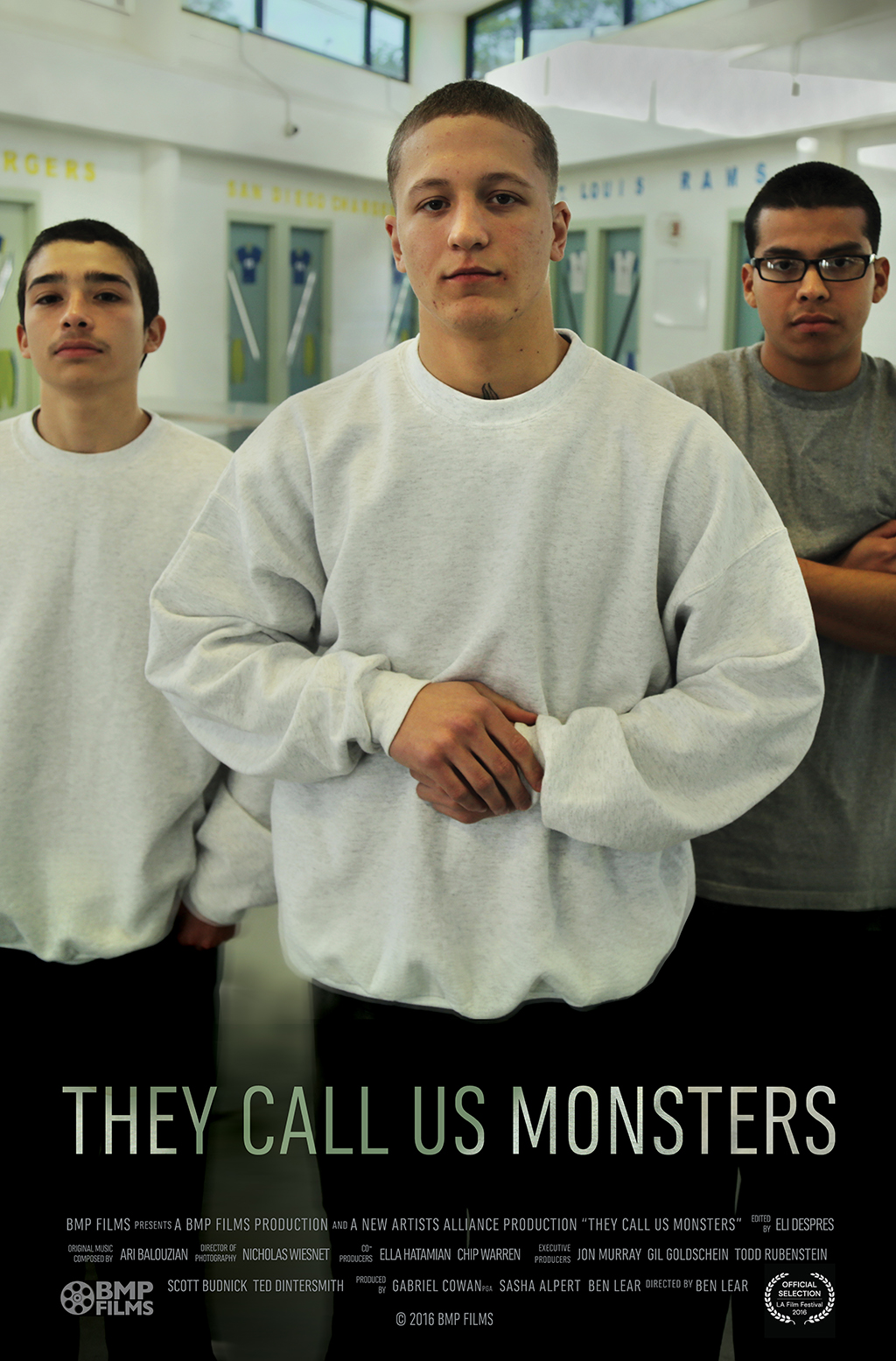

Juan Gamez, Antonio Hernandez and Jarad Nava are the youthful offenders at the heart of “They Call Us Monsters,” a new documentary that follows their lives in a Los Angeles juvenile detention center. They’re held in a special wing of the lockup reserved for teens who will be standing trial as adults. All three are looking at terms that could keep them behind bars for decades.

Their stories are framed by their participation in a screenwriting class taught by Gabriel Cowan, one of the documentary’s producers — and by the debate among California lawmakers over a bill that would grant young offenders with lengthy terms a chance at parole after 15 years. Supporters of that measure cited new science about brain development in teenagers that found the part of the brain that regulates judgment, decision-making and impulse control doesn’t fully form until a person is in their 20s.

“The entire area of the brain that pertains to culpability and consequence and long-term thinking and impulsivity — everything that comes together in the commission of a crime — is not developed,” the film’s director, Ben Lear, told Youth Today.

“It’s not an excuse by any means. These people have to do their time. They have to pay for what they did,” Lear said. “But because you do not know who they will turn out to be when they are 25, 26 or 27, I feel as a society that we do have the obligation to provide them an opportunity to earn a second chance, based on that fact.”

Juan and Jarad were 16 when they were arrested; Antonio was 14. Juan was charged with murder, while Jarad and Antonio were accused of attempted murder.

Juan’s older brother drew him into gang life as a child in their native El Salvador, before they moved to California. Antonio, a methamphetamine addict, recounts seeing a man shot to death in front of him when he was 8, but insists he’s not traumatized: “I guess you do kind of get used to it.” And when he was 12, Jarad found his stepfather trying to stab himself to death — an unsuccessful attempt that nonetheless resulted in the breakup of his family.

While the film includes some touching moments, like Juan’s brief visits with his toddler son and a goodbye call to the girl he never expects to see again, it doesn’t flinch from its subjects’ culpability. Jarad’s victim describes waking up paralyzed, and the film shows her trying to navigate her apartment in a wheelchair. Juan says, “I really was a monster,” and the film includes surveillance video of the killing that put him behind bars. Antonio admits he feels no remorse for his actions, and his promising new start sours soon after his release.

“You can look at that and say, ‘OK, they’re obviously sociopaths.’ But what I would encourage people to do is peel a layer off, go a little bit deeper and entertain the idea that maybe they’re temporarily sociopaths,” Lear said. “Maybe that journey toward remorse and responsibility is different for everyone. Maybe it takes 10 years. Maybe it takes 15 years. Maybe it takes a lifetime.”

Lear, the son of television producer and liberal activist Norman Lear, was drawn to the issue after he was invited to sit in on one of the scriptwriting classes run by InsideOUT Writers, a Los Angeles-based organization that teaches creative writing to kids in juvenile lockups. He went as research for a script, expecting to meet the kind of scary characters he’d seen in the movies — but instead, he found “a classroom full of kids.”

“When a kid arrives there, a lot of his baggage is temporarily stripped away,” Lear said. “He’s no longer actively gangbanging. It’s a lot harder for him to find drugs. So most of the time, it’s easier for them to just be kids when they’re locked up.”

That inspired him to make the documentary, which uses a montage of news reports to illustrate the late 20th century spike in juvenile crime and the punitive response that followed — a broad expansion in the offenses and ages for which a teen could stand trial as an adult. By 2010, about 250,000 teens were being prosecuted in adult courts every year, according to the Campaign for Youth Justice, which opposes the practice.

In the past few years, however, officials in many states and in Washington, D.C., have been rethinking the clampdown. In California, the parole bill featured in “Monsters” ultimately passed in 2013. That state’s legislature also eliminated the chance of life-without-parole sentences for all but a few juvenile offenders and made more young inmates eligible for early parole.

And in 2016, state voters approved a ballot measure that takes the decision on whether a teen should stand trial as an adult away from prosecutors and puts it in the hands of a juvenile court judge. Juvenile court judges had made that decision until 2000, when a referendum gave prosecutors the power to try teens as adults for certain serious crimes.

For Lear, who now sits on the InsideOUT Writers advisory board, the shift has been heartening. When California advocates began pushing to scale back punishments for offenders like those in his film, Lear said, it seemed hopeless. But each successive measure has passed “with more and more support.”

“California seems to be well on the right path, but there are a lot of states that are much further behind in that conversation,” he said. “I want the film to reach those legislative buildings, those communities, to start a conversation around this population and how it should be treated.”

Hello. We have a small favor to ask. Advertising revenues across the media are falling fast. You can see why we need to ask for your help. Our independent journalism on the juvenile justice system takes a lot of time, money and hard work to produce. But we believe it’s crucial — and we think you agree.

If everyone who reads our reporting helps to pay for it, our future would be much more secure. Every bit helps.

Thanks for listening.

Contribute Now