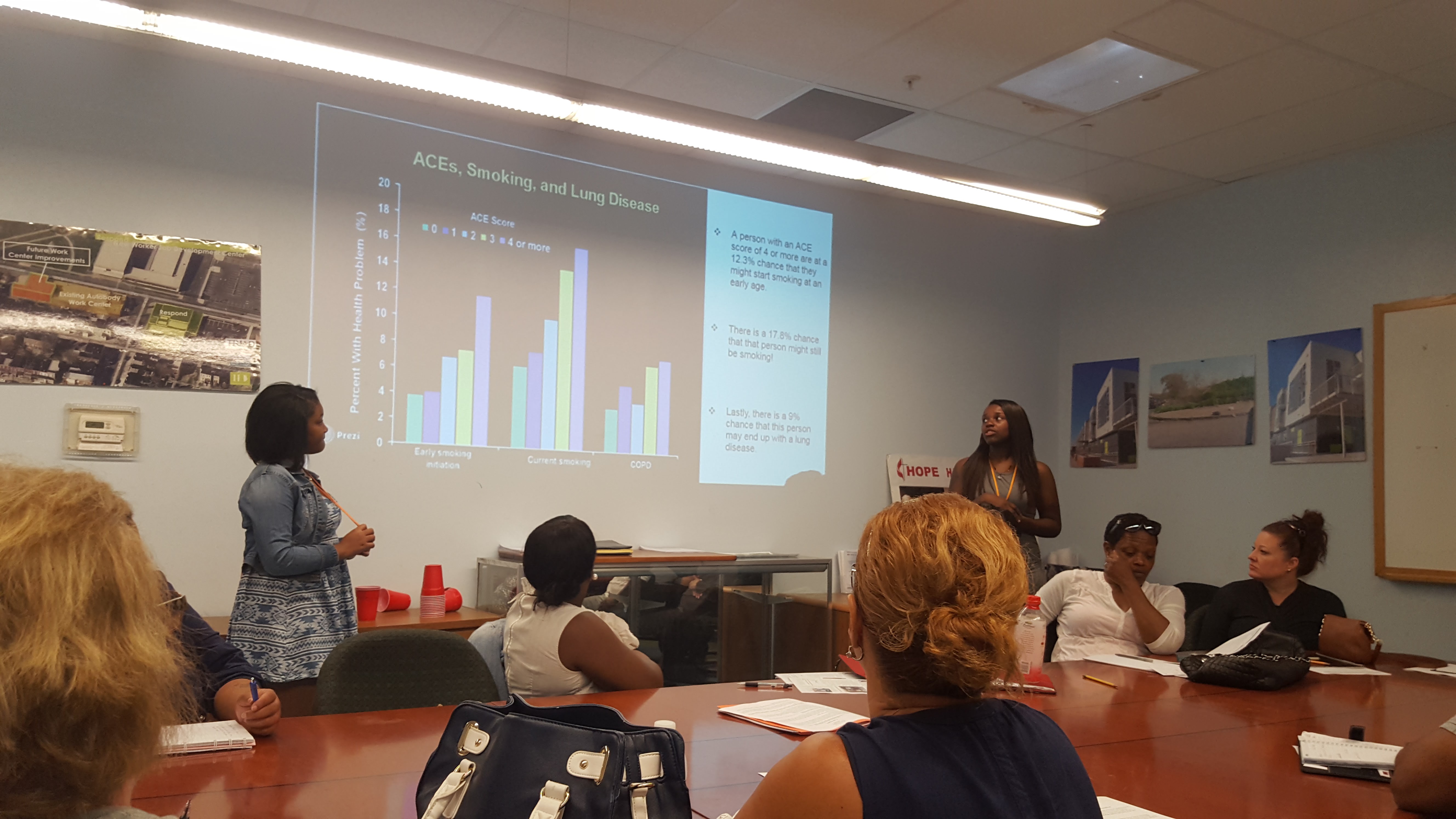

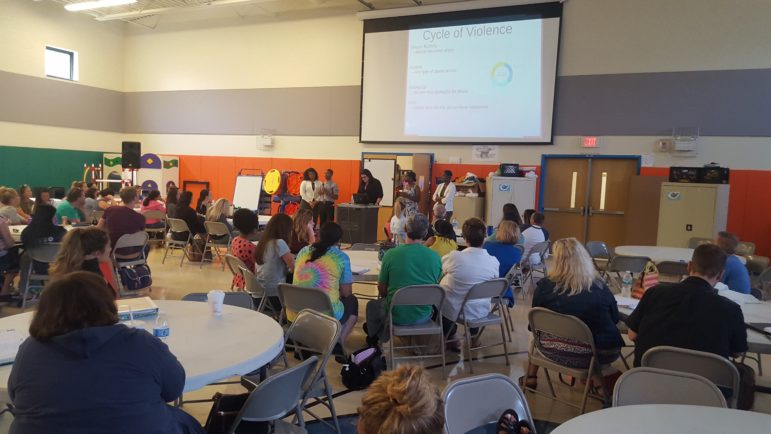

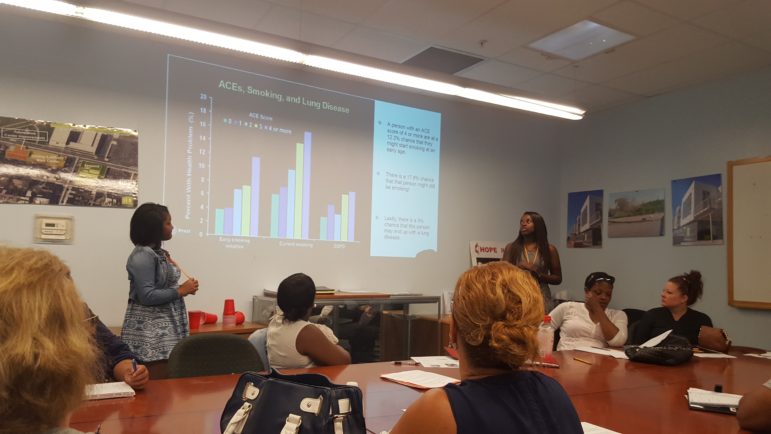

Photos courtesy of Hopeworks

Samples of the Youth Healing Team training

Two volunteers race against the clock to stack red Solo cups into the highest tower they can manage.

Queenie Smith keeps knocking them down.

After the one-minute exercise, Smith, 16, who is leading this hour-long training on trauma and resilience along with two colleagues, explains to her audience that the game is a metaphor: “You constantly build up your life goals, but ACEs keep knocking them down.”

The exercise works because participants respond in exactly the same way individuals respond to adversity: Some give up in frustration, some lower their standards, and some just keep plugging away.

It’s also a powerful exercise because Smith and her co-trainers are teenagers, members of the Youth Healing Team at Hopeworks ‘N Camden, an organization that uses a trauma-informed approach while teaching web design and other skills to help youth ages 14 to 23 return to school or find meaningful work.

Since 2014, the Youth Healing Team has trained 900 people in more than 30 different sessions. Their biggest client is the Camden School District. They have also trained Teach for America fellows, members of the Camden Coalition of Healthcare Providers, and staff at Rutgers University.

Dan Rhoton, Hopeworks’ executive director, says the Youth Healing Team grew from an awareness among staff members that adults might not be the most potent carriers of information about ACEs and resilience.

“We found that our youth were much more effective,” he said. “Before, staff members and I would go talk to folks. People would say, ‘What a great presentation.’ Then we’d go back [to the same organization or audience], and nothing was different.”

The youth suggested more interactive ways of presenting material—the cup game, for instance, and a balloon toss in which volunteers are given different, conflicting instructions for playing, leading to follow-up discussion of how children exposed to trauma grow up with different “rules.” The youth also brought the power of lived experience.

“When I give a speech to teachers at a school, they think, ‘Oh, that would never work with my kids,’” Rhoton says. “When we have a young person who says, ‘I have an ACE score of 7, and this is how the safety plan helps me,’ that’s different.”

Youth Healing Team members learned the basic training information—definitions of trauma and adversity, the ACE survey, self-care strategies. Their one-hour version incorporates clips from Madea movies, a student-written rap, reflection, questions and a demonstration of “the huddle,” a check-in ritual that starts every day at Hopeworks.

When the Youth Healing Team began its trainings, members frequently disclosed their own histories: homelessness, violence, abandonment. But they discovered that such sharing didn’t necessarily lead to the outcomes they wanted.

“If a young person told a trauma story, we were guaranteed two things,” Rhoton says. “Everyone would cry, and no one would change their behavior.” Audiences listening to such “horrific/heroic” stories tended to focus on the speaker’s survival rather than their own experiences of trauma or capacity to help others.

But when the youth focused on the science of ACEs and the tools that build resilience, their listeners’ questions changed. Teachers began to ask, “How do I do this in my classroom if I have only ten minutes? How can I do this with kindergarteners?”

Other communities are similarly harnessing the voices and experiences of young people in the effort to build resilience. For example, participants in Kansas City’s Youth Ambassadors, an educational work program that aims to empower underserved teenagers, have produced documentaries and held public journal readings to educate audiences about issues facing local youth. Teenagers from Gillis, another Kansas City program for at-risk children and families, recorded a rap album with songs that chronicle their struggles, hopes and ambitions. And in Philadelphia, middle- and high school students at the Village of Arts and Humanities work with professional artists to co-create music, photography, and digital storytelling projects that highlight youth perspectives.

Back in Hopeworks’ second-floor conference room, Smith, 16, and her co-trainers hand their listeners small white cards and indelible markers, instructing them to jot down three things they can do if they feel frustrated, angry or unsafe during the work day. “On my safety plan is: Take three breaths, think of something funny, or talk to a co-worker,” Smith says.

Then they explain and demonstrate “the huddle,” a check-in circle grounded in the Sanctuary Model’s community meeting practice in which each participant asks the next person four questions: How do you feel today? How do you want to feel later? What is your key goal for today? Who can help or encourage you?

When a participant tries this out with trainer Gemyra Winn, 17, Winn says she is frustrated but would like to feel accomplished, that her goal is to finish the workshop and that Smith can help.

Winn, Smith and Aunyay Fussel, 16, all say that being part of the Youth Healing Team has changed the way they see themselves and the way they regard their community.

“I never knew what trauma was, but now I see it all the time in my neighborhood,” says Smith. At school, she says, teachers often label a difficult student with ADHD or another diagnosis, not recognizing that the student may be acting out because of something troubling at home.

The trainings that include Camden teachers are the most gratifying, the teens say, because the knowledge they share can have an impact on future generations of students. “We just want to change how people think,” says Fussel, “and make our community better.”

- Watch one of Hopeworks’ Youth Healing Team’s presentations.

- Learn more about Safety Plans and Community Meetings from Dr. Sandra Bloom (2010).

- FOR MORE INFORMATION ABOUT MENTAL HEALTH AND YOUTH, GO TO THE YOUTH TODAY OST HUB.

This article first appeared on the Mobilizing Action for Resilient Communities website.