|

|

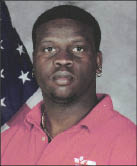

De’Janaria Austin |

De’Janaria Austin moved from one military youth program to another as his Air Force father moved the family from Myrtle Beach, S.C., where Austin was born, to military bases in Virginia, Georgia, the Philippines and Nevada.

Today, at 32, he’s the sports director for the very program he attended as a child at that last stop: Nellis Air Force Base in Nevada. His path there was circuitous.

Austin began playing soccer and football at Langley Air Force Base in Virginia at age 5. Three years later, he was at Clark Air Force Base in the Philippines, where he was a soccer forward and, in sudden death overtimes, the goalie. Then, he says, he “mastered my skills” at the Valdosta base in Georgia as the football team’s star quarterback.

“They had a small youth program there we’d frequent every day. You’d do your homework, buy your snacks, and in the afternoon play youth football and youth soccer.

“You met so many people,” he recalls. “Your coaches were military, so they had the same values. Sportsmanship was big. We weren’t out there taunting people.”

Moving to Nellis when he was in the 10th grade “was like my wake-up,” he says. “Everywhere else I’d been the star, sheltered on the base.” At Rancho High School, in a tough Las Vegas neighborhood, Austin soon learned that the colors of his clothes had gang connotations. The school population was largely African-American (as is Austin) and Hispanic. Tensions were high.

“The Nellis youth program kind of kept me grounded,” he says. “If the school had been my only surroundings, I would’ve wound up like them,” in trouble with the law, unemployed or in a dead-end job. “But I’d go back to Nellis, tell my coach what I’d seen, about somebody getting beat up, and he’d say, ‘You don’t have to be like that.’ Luckily, I had a good head on my shoulders. I had my own gang – Nellis Air Force Base.”

When he turned 18, he aged out of the youth programs. He started at a local college and worked as a dishwasher at the Nellis officers’ club, often swinging by the youth center “to see who was still working there.”

Austin flunked out of college, and turned once again to Nellis – working up to six hours a day, for $8 an hour, in the youth center’s before- and after-school program. He taught basketball as well as arts and crafts, helped youths with homework, showed them how to use a computer and made sure they got on and off the right bus.

In five years, he moved up to floor supervisor, in charge of other youth workers. He earned $13 an hour, full time. Realizing that he’d hit a salary ceiling, Austin returned to school, where he garnered mostly As and Bs, but ran into financial problems and left again.

Nellis came knocking. The sports director for the youth program was leaving. Would he like the job?

Some 1,200 children are enrolled in the Nellis sports programs under Austin’s direction. He is attending the University of Nevada-Las Vegas part time, with 36 credits left, to complete his degree in recreation and sports management.

“Once I get my degree, it opens up,” he says. “I can be youth director, school-age director. But I don’t want to do anything but sports. I want to do some more time here.”