|

|

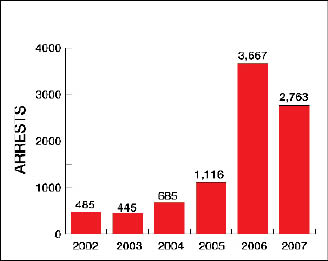

Crackdowns on Illegal Immigrants: Administrative arrests by fiscal year |

As federal immigration authorities raided a New Bedford, Mass., manufacturing plant in March, netting 361 undocumented aliens, Helena Marques stood outside, looking nervously at her watch.

With local schools about to let out, the executive director of the town’s Immigrant Assistance Center says she pleaded with the U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) officials to let her know what arrangements were being made for children whose parents were being detained.

Soon, her organization was scrambling with the local social service and faith-based agencies to ensure that children temporarily separated from their parents were cared for.

The public firestorm that followed shed light on a sensitive issue: How much should ICE help child welfare workers reach children whose parents are arrested in immigration raids?

ICE is not required to do much, although some state legislators and congressmen are pressing to change that. Whatever happens, child welfare agencies in areas with a lot of illegal immigrants should be prepared: Such raids are becoming more frequent.

ICE’s “administrative arrests” – which are for immigration violations – increased by 750 percent from 2002 to 2006, and the agency is on pace to exceed last year’s total of more than 3,600. One reason: the pressure in Washington to crack down on illegal immigrants as part of immigration reform.

Not all of those raids leave children unattended, and when they do, some child welfare agencies handle the sudden influx through standard emergency response plans. But the New Bedford raid, along with recent raids in California and New Mexico, exposed a sore spot – albeit one on which not all child welfare administrators agree.

“We can’t say anything because it’s a hot-potato issue between social welfare people,” said Frank Solomon, spokesman for the American Public Human Service Association/National Association of Public Child Welfare Administrators.

Limits of Cooperation

ICE does not have to inform local social service agencies about an impending raid. The department says that leading up to the New Bedford raid on Michael Bianco Inc., a leather goods manufacturer, it contacted state officials anyway.

But Juan Martinez, communications director for the state Office of Health and Human Services (HHS), said via e-mail that ICE “was only in touch with our public safety office because they needed state police escorts to transport detainees.”

Martinez said the public safety office asked ICE to have staff from the Department of Social Services (DSS), which handles child welfare placements, “on the ground as the raid was happening, so we could have IDed [identified] caretakers and children immediately. We were not allowed to do this, but it would have been quite helpful.”

ICE says notifying local social service agencies ahead of time might jeopardize the law enforcement operation. However, police have worked with social service agencies around the country on some operations, including raids of homes where methamphetamine was produced, to ensure the safety of children whose parents might be arrested.

After a raid comes the question of getting access to parents who are detained.

ICE vociferously defends its treatment of detainees who have children. It says sole caregivers are routinely released after being fingerprinted and processed for removal from the United States, as was done in New Bedford.

“Everybody who’s arrested is asked about humanitarian issues,” said Tim Counts, an ICE spokesman in the Minneapolis/St. Paul area, where a major raid occurred in April. The reality, he said, is that “people lie to us” about whether they have children.

Immigration advocates acknowledge that illegal immigrants are often afraid to tell immigration officials about their children, for fear that the children or their other caregivers will be apprehended as well.

After the New Bedford raid began, the state DSS says ICE took more than 24 hours to let its workers interview the detainees to find out about children who might need care. Some DSS staffers had to fly to an ICE detention facility in Texas to interview parents who had been taken there.

“The delay caused unnecessary suffering for many children, their parents and the greater community,” Massachusetts HHS Secretary JudyAnn Bigby said in lambasting ICE at a special state legislative hearing last month. “Much of this crisis could have been avoided had there been written federal humanitarian policies in place.”

Bigby said that “federal authorities should work with local officials to identify mutually agreed upon procedures that enable human services providers to be in contact with detainees in a secure setting. The policy should allow human services workers to meet with detainees to identify individual circumstances that put themselves, their children and other vulnerable people, such as the elderly, at risk.”

ICE said the DSS was given broad access to all detainees, that several were let go immediately or within days of the operation, and that no children were placed in foster care as a result of the operation.

Some members of Congress, including Sen. Edward Kennedy (D-Mass.), demanded changes in ICE procedures, with Rep. William Delahunt (D-Mass.) pledging hearings by the House Judiciary subcommittee on Immigration.

Living with It

It’s difficult to tell if the occasional objections will translate into changes.

When 30 undocumented workers were arrested in a raid in February in Santa Fe, N.M., local officials widely denounced the raids for their effect on children. “Families are being torn apart, literally,” Mayor David Coss publicly declared.

The American Civil Liberties Union has filed a request for ICE records surrounding that raid, as well as raids in California, in response to news reports about inappropriate tactics, including round-ups taking place near schools and minor children left unattended after their parents were arrested.

But the raids don’t always produce conflicts with local officials. After a raid in Baltimore in late March netted 69 alleged immigration law violators, the city’s Department of Social Services got no emergency referrals, said department spokeswoman Sue Fitzsimmons. The department reported no problems with how ICE handled the case.

As with several recent raids, ICE issued a news release noting that the detainees were interviewed by local human services officials and were offered access to child protective services.

In Massachusetts, State Sen. Karen Spilka (D) plans to draft child welfare recommendations for the congressional delegation and for state and local officials on how ICE raids should be handled, said her spokeswoman, Sarah Blodgett.

In the end, the amount of cooperation with child welfare is up to ICE. “ICE holds all the cards,” said David Leopold, a national leader of the American Immigration Lawyers Association and an immigration attorney in Cleveland.

He said ICE can mitigate the impact of raids on children by releasing on bond undocumented workers who don’t pose a flight risk or who aren’t dangerous.

“Nobody is advocating that people work in this country without documentation, unlawfully,” Leopold said. But unless Congress makes the immigration system more rational, he said, the “collateral damage” on children will continue.

Jen Russell contributed to this report.