Wide Angle Youth Media

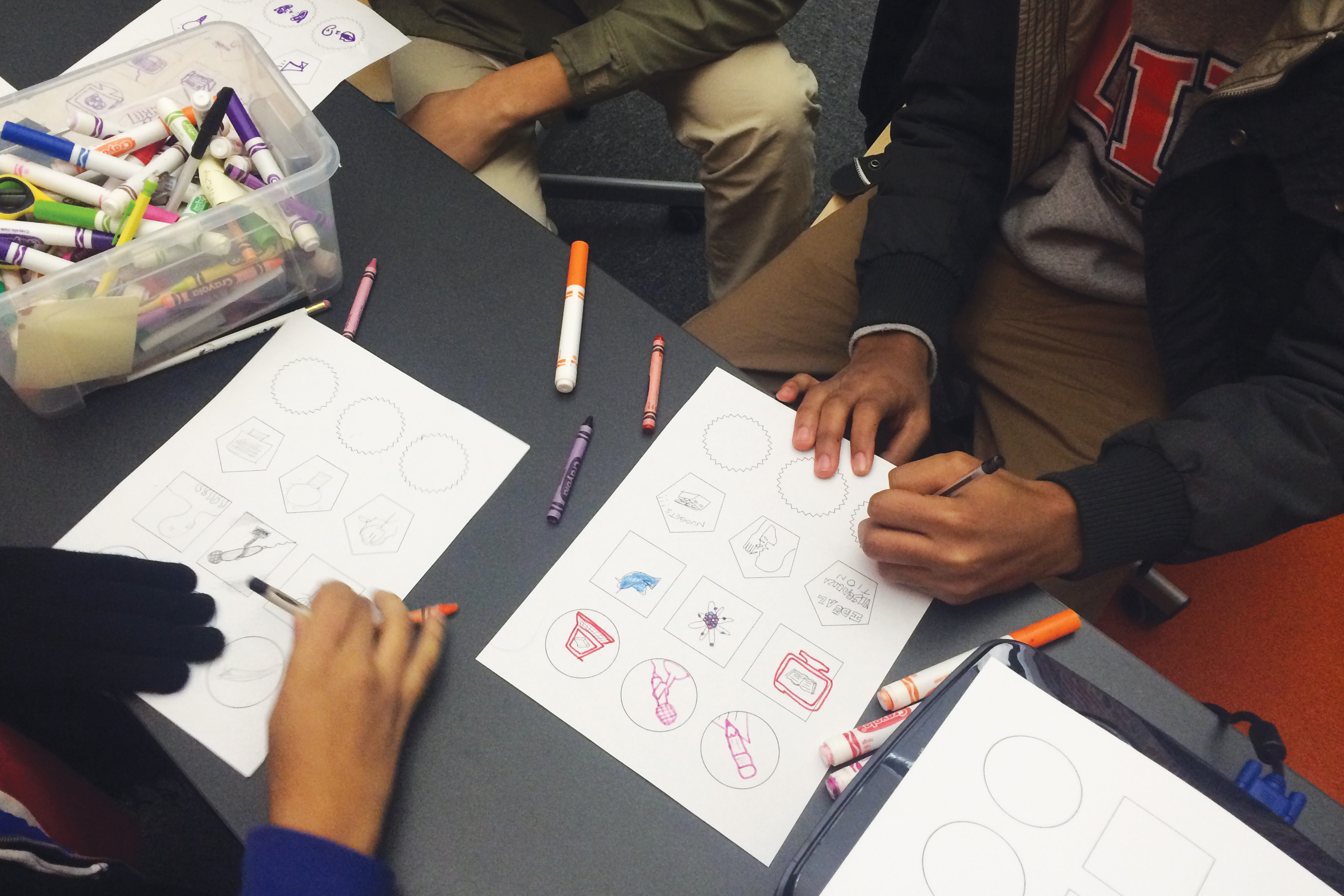

Students in Wide Angle Youth Media’s initial badge project had a chance to create the look for the new badges in public speaking, idea visualization and digital storytelling.

This past spring, Laurell Glenn, then a senior at Baltimore’s Digital Harbor High School, faced an audience of college students, faculty and community members at Loyola University Baltimore. She was the sole high school student on a panel discussing school suspension — the culmination of work in an after-school program where she gained many skills, including public speaking.

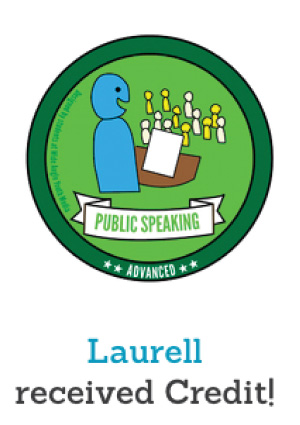

Her presentation also netted her a digital badge in public speaking from Wide Angle Youth Media, a nonprofit program that provides media education to Baltimore youth.

“I was a very shy person. I wasn’t comfortable in voicing my opinions and speaking out. [At Wide Angle Youth Media] they encouraged me to do that.”

The digital badge also motivated her, Glenn said.

Digital badges are credentials posted online that recognize the acquisition of skills and knowledge. A number of out-of-school time programs are excited about them as a way to widen opportunities for low-income kids as well as to create new pathways for all kids. For example, last year the Afterschool Alliance, with a grant from the MacArthur Foundation, supported digital badge pilot projects in Maryland, Michigan, Ohio, Oregon and Rhode Island.

Show what you know

The idea of badges is not new: Girl Scouts and Boy Scouts have offered them for years. Digital badges, however, are posted online by a third party for viewing by potential employers, college admissions officers and others. Third-party badge issuing platforms include Mozilla Open Badges, Credly and Badgr.

[module type=”aside” align=”right”] Find articles, research and resources on Program Quality in the out-of-school time at the Youth Today Out-of-School Time Research and Resource Hub.

Find articles, research and resources on Program Quality in the out-of-school time at the Youth Today Out-of-School Time Research and Resource Hub.

“I uploaded it to my LinkedIn account,” Glenn said, where her badge is accompanied by pictures of the Loyola event and the criteria for earning the badge. Wide Angle Youth Media used badge issuer Credly, which connects with LinkedIn, and kids who worked to earn badges learned how to create a LinkedIn account as part of the process.

Sheila Wells, development and communications director of Wide Angle Youth Media, said young people are learning many things, but their skills don’t always show up on report cards and college applications — particularly things they learn in out-of-school time and in the arts. Badges convey the development of “soft skills” more than a resume can, she said.

“It would be really cool when you click on the badge to be able to see the portfolio of work the student has made,” said Wells.

She’d love to see badges used in the college admission process. “It would be a game-changer.”

In order for badges to work, “we’re going to need to see buy-in from employers and higher education,” she said.

Recognition for OST learning

Wide Angle Youth Media’s badge project began a year ago in its Attendance and Design Team, a group of 12 high school-aged students who meet four to six hours per week and design six marketing campaigns to improve school attendance rates. They gain advanced graphic design skills and media training while also developing public speaking, leadership and marketing skills. The goal is to help them develop both technical and soft skills, Wells said.

Badges were offered in three categories: public speaking, digital storytelling and idea visualization. The staff at Wide Angle Youth Media worked with the Baltimore school district to set the criteria for earning badges, aligning the criteria with Common Core Standards and National Media Arts Standards. Students who were working to gain badges, as well as Wide Angle Youth Media staff, judged whether each participant met the criteria to earn the badge.

Glenn gained a second badge in idea visualization, the translation of sketches to a digital format.

The students also designed logos for these new badges, Well said.

“They were excited,” she said. “They hadn’t had the opportunity to promote themselves.”

U.S. Secretary of Education Arne Duncan spoke enthusiastically about digital badges at the MacArthur Foundation’s 2011 Digital Media and Lifelong Learning Competition.

The badges “can broaden the avenues for learners of all ages to acquire and demonstrate — as well as document and display — their skills,” he said.

Wide Angle Youth Media

Attendance and Design Team students Laurell and Tyecel with assistant media instructor Chaya.

The can help account for both formal and informal learning, he said.

“We need to recognize these experiences, whether the environments are physical or online, and whether learning takes place in schools, colleges or adult education centers, or in afterschool, workplace, military or community settings.”

“Badges can help speed the shift from credentials that simply measure seat time, to ones that more accurately measure competency,” he said.

With support from the MacArthur Foundation, Internet service provider Mozilla launched Open Badges in 2011, a website where any organization can issue verified badges.

The digital revolution

The idea of digital badges grew out of online gaming, where they were used to identify players and show how they had performed. In many ways, digital badges are a response to the Internet revolution, which has made a vast amount of information available outside of traditional educational institutions.

Colleges in particular are trying to figure out how to best make use of new educational tools, such as massive open online courses, and how to offer credentials in a world in which students may jump from college to college and online course to online course.

The After-School Corporation (TASC), a New York-based nonprofit, produced a brief in 2012 on the need for additional credentialing opportunities such as digital badges.

[Related: Using Online App to Implement Each One Teach One]

Teenagers should have the chance to learn outside of traditional classrooms, according to the After-School Corporation. Such opportunities would benefit the high number of school leavers — many of whom are young black men, the organization said in a 2012 brief.

But all students could benefit — from accelerated ones to those who are “under-credited” and in danger of quitting school, according to TASC.

“Students need more ways to pursue knowledge and interests beyond their schools’ curricula,” the brief asserted.

Value and credibility?

In 2012, the Providence (R.I.) After School Alliance (PASA) began awarding badges in its after-school program for high school students known as the Hub. The project was funded by a grant from the MacArthur Foundation’s Badges for Lifelong Learning Competition.

The Hub was already providing expanded learning for kids, including courses that could be used for high school credit. Then it began offering badges as an alternative credentialing system for teens in areas such as web development.

But after an evaluation of the program by University of Washington researchers Katie Davis and Simrat Singh, the organization stopped issuing the badges.

The problem seemed to be that the badges had no recognized value.

In evaluating the program, researchers interviewed 43 students, 24 teachers and mentors, and one college admissions director.

Credibility was the biggest issue noted by the researchers. Students and adults alike said that credibility rests on college admissions officers and employers knowing about and recognizing the validity of badges.

There was “a lack of stakeholder buy-in,” Davis and Singh wrote in their report “Digital badges in afterschool learning: Documenting the perspectives and experiences of students and educators,” published in 2015.

Students, as well as colleges and employers, did not always buy the idea.

“Quite frankly, I think for many students right now, they (a) don’t know what a badge is, and (b) don’t give a crap about a badge. I think it’s an adult construct, by and large.” said one adult quoted in the report.

But adults also saw possibilities.

Laurell’s badge for public speaking.

“Adult participants saw the potential for badges to give non-dominant youth a means to package their skills and accomplishments for audiences like college admissions officers and prospective employers,” the report said.

They can help kids talk about the skills they’ve gained and help them create a positive online presence, one adult told the researchers.

Adults also said the badges provide something for low-income kids that otherwise isn’t available.

“If my kid can HTML code and he’s competing against a bunch of kids that have more opportunities, more affluent backgrounds, like that’s sort of where we’re positioned to make a difference [with badges],” one survey respondent said.

PASA is now in the process of reviewing and retooling the digital badge program.

“Over and over again, high school youth have told us that if we want them to buy into and adopt badges as a valuable marker of their learning, they’ll have to unlock real world benefits not available through more traditional means,” according to the PASA website.

At bottom, digital badges are only as valuable as the larger system that acknowledges and recognizes them to mean something. Their value rests on the credibility of the issuing institution and the usefulness of the badge to a school or employer who has the power to provide something in return.

Alejandro Molina, PASA deputy director, said that what kids found valuable in the badging program was the experience of the course or internship itself and the connection to a caring adult.

“We took that to heart,” Molina said.

“We haven’t given up,” he said. “We needed to go back to the drawing board.

“We believe in badges. We just want to get it right,” he said.

Digital badges in Boston

A large after-school organization experimenting with digital badges is Boston After School & Beyond, which works with 100 community partners and 50 schools to reach 10,000 children, said Executive Director Chris Smith. It already partners with a number of community organizations that play a role in kids getting school credit.

But for the first time this summer, the organization piloted a digital badge program. Kids in five summer STEM programs had the chance to earn achievement badges, not on the STEM content, but on the skills of critical thinking, perseverance, collaboration and communication, Smith said. These skills are related to the Next Generation Science Standards developed by the National Research Council and others.

The goal is to help kids internalize and represent what they’ve learned, he said.

“We want to learn whether this mini-credential [effectively] recognizes the accomplishment and growth that kids make,” he said.

More info and resources

- “Digital Badges in Afterschool: Connected Learning in a Connected World,” published by Afterschool Alliance, July 2015.

- “Expanding Education and Workforce Opportunities Through Digital Badges,” a 2013 report by the Alliance for Excellent Education and the Mozilla Foundation.

- “7 Things You Should Know About … Badges,” by Educause Learning Initiative, a group of information technology professionals focusing on higher education.

- Mozilla Open Badges, a platform for organizations wanting to issue badges and learners to display them.

- MacArthur Foundation digital badge projects.

- “Digital badges in afterschool learning: Documenting the perspectives and experiences of students and educators,” by Katie Davis and Simrat Singh. Computers and Education journal, April 2015. This article is available for a fee.

More related articles:

Want a Citywide After-school System? Here’s What You Probably Need

Pro-social Skills at Young Age Can Predict Future Success, Study Says

Support Quality After-School Programming: Upending Conventional Wisdom

Camp Fire Embraces Thriveology