How would you feel if your child were being tutored by a robot?

Social robots – robots that can talk and mimic and respond to human emotion – have been introduced into classrooms around the world. Researchers have used them to read stories to preschool students in Singapore, help 12-year-olds in Iran learn English, improve handwriting among young children in Switzerland and teach students with autism in England appropriate physical distance during social interactions.

Some experts believe these robots could become “as common as paper, whiteboards and computer tablets” in schools.

Robots currently used in schools are finicky and limited in functions.

Because social robots have a body, humans react to them differently than we do to a computer screen. Studies have shown that little children sometimes accept social robots as peers. For example, in the handwriting study, a 5-year-old boy continued to send letters to the robot months after the interactions ended.

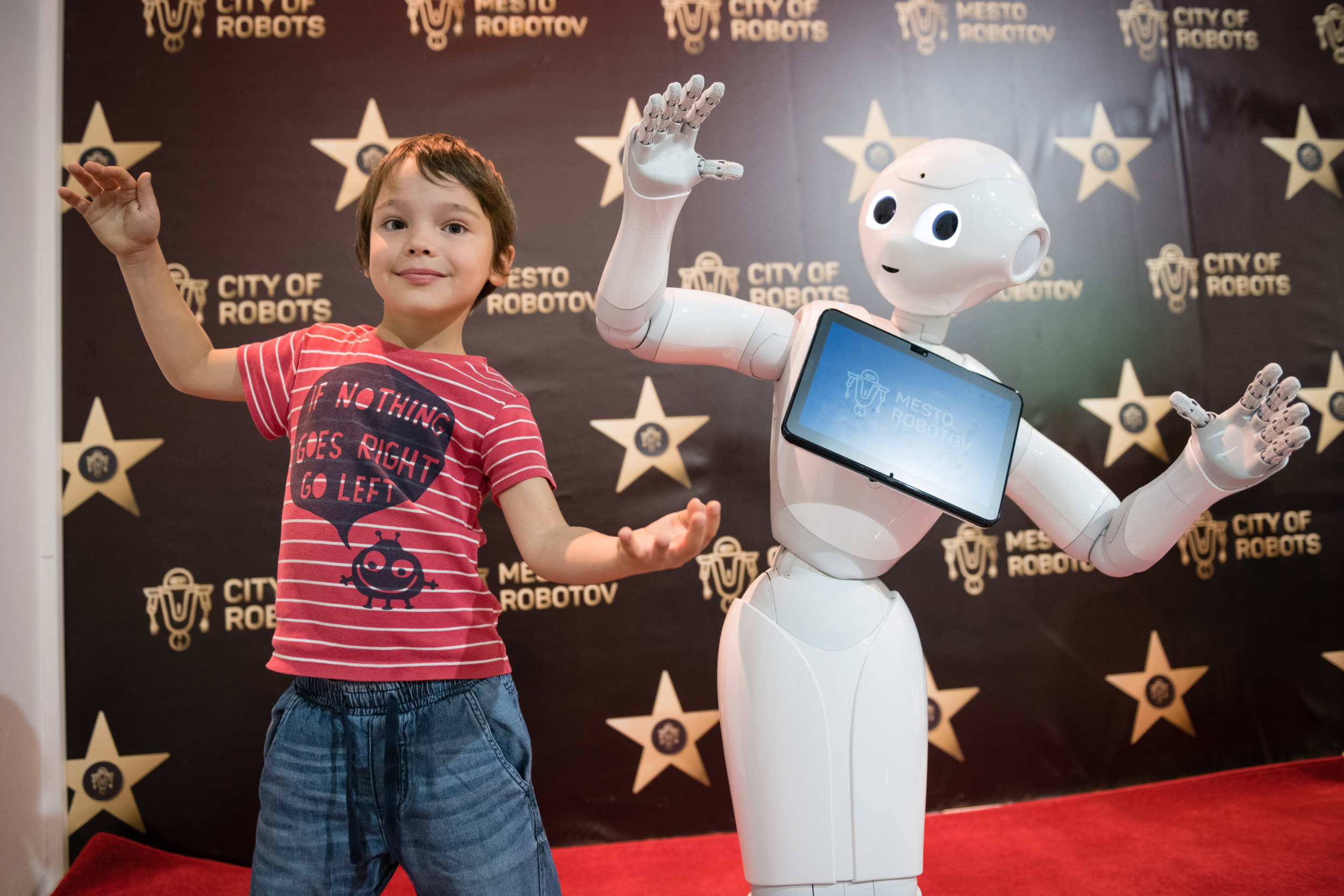

As a professor of education, I study the different ways that teachers around the world do their jobs. To understand how social robots could affect teaching, graduate student Raisa Gray and I introduced a 4-foot-tall humanoid robot called “Pepper” into a public elementary and middle school in the U.S. Our research revealed many problems with the current generation of social robots, making it unlikely that social robots will be running classrooms anytime soon.

Not ready for prime time

Much of the research on social robots in schools is done in very restricted ways. Children and social robots are not allowed to freely interact with each other without the assistance, or intervention, of researchers. Only a few studies have used social robots in real-life classroom settings.

Also, robotic researchers often use “Wizard of Oz” techniques in classroom settings. That means that a person is operating the robot remotely, giving the impression that the robot can really talk to humans.

Limited social skills

Robots need quiet.

Any kind of background noise – class-change bells, loudspeaker announcements or other conversations – can disrupt the robot’s ability to follow a conversation. This is one of the major problems facing the integration of robots into schools.

Ventura/Shutterstock

Students often talk to and interact with ‘Pepper’ robot as if it were a person. Young elementary student interacts with Pepper.

It is extremely difficult for programmers to create software and hardware systems that can achieve what humans do unconsciously. For example, the current generation of social robots cannot interact with a small group and, for example, track multiple people’s facial expressions. If a person is talking to two other people about their favorite football team and one of the listeners frowns or rolls their eyes, a human will likely pick up on that.

A robot will not.

Also, unless a bar code or other identification device is used, today’s social robots cannot recognize individuals. This makes it very unlikely for them to have realistic social interactions. Facial recognition software is difficult to use in a room full of moving, shifting people, and also raises serious ethical questions about keeping students’ personal information safe.

Dialogue is preprogrammed

To get the robot to perform, our students had to master the tutorials that came with the robot. Some students quickly figured out that the robot could respond only to certain basic routines.

Robots act as a bridge in enabling students to understand humans.

For example, Pepper could respond to “How old are you?” but not “What age are you?” Other students kept trying to interact with the robot as if it were a person and got very frustrated with its nonhuman responses.

When a robot fails to answer a question, or responds in the wrong way, students realize the robot isn’t really understanding them and that the robot’s dialogue is preprogrammed. The robot can’t really make sense of the social context.

In our study, students learned to adapt to the robot.

One group of girls would stand around the robot while one kept petting its head. This caused the robot to do either its “I feel like a cat” or its “I’m ticklish today” routine. This seemed to delight the girls. They appeared content to have one person interact with the robot while others watched.

Cannot move around classroom with ease

Students who have seen YouTube videos of robotic dogs that run and jump may be disappointed to realize that most social robots can’t move around a classroom with ease. The teachers in our study were disappointed that Pepper couldn’t bring them coffee.

These problems aren’t limited to school settings.

Service robots in some health care facilities have been programmed to deliver medicine, but this requires special sensors and programming. And while stores and restaurants are experimenting with delivery and cleaning robots, when a grocery store in Scotland tried to use Pepper for customer interactions, the robot was fired after a week.

What social robots can teach kids

While the social robots currently used in schools are finicky and limited in functions, they can still provide useful learning experiences. Students can use them to learn more about robotics, artificial intelligence and the complexity of real human behavior.

As one researcher wrote, “Robots act as a bridge in enabling students to understand humans.”

[Related: 7 AI trends that could reshape education in 2024]

Social robots provide students with learning opportunities about AI.

Struggling with a robot’s limitations gives students real insights into the complicated nature of human social interaction. The opportunity to work hands-on with a social robot shows students how difficult it is to program robots to mimic human behavior.

Social robots can also provide students with important learning opportunities about artificial intelligence. In Japan, Pepper is being used to introduce students to generative AI. Students can link ChatGPT with Pepper’s physical presence to see how much AI improves Pepper’s communication and whether that makes it more lifelike.

As AI becomes a bigger part of our work and lives, educators need to prepare students to think critically about what it means to live and work with social machines. And with a real human teacher’s guidance and oversight, students can explore why we want to talk to robots as if they were people.![]()

***

Gerald K. LeTendre, is a professor of Educational Administration at Penn State. His current research interests include changing work roles for teachers cross-nationally and the impact of online education on teacher professional status.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.