The first and only time Malik Rainey was arrested, he was 16 and charged, as an adult, with possession of a loaded firearm. But instead of serving what could have been up to 12 years in prison, he wound up in a court-mandated program that kept him out from behind bars as long as he stayed away from crime, and got an education and a job.

Rainey, now 22, got that second chance largely because Avenues for Justice intervened on his behalf. As Rainey and his mother sat in a Manhattan courtroom waiting for a judge to hear the teen’s case, an advocate from the nonprofit Avenues introduced himself. Alongside the mom and son, that advocate listened to the details of Rainey’s case, then later explained how Avenues could help.

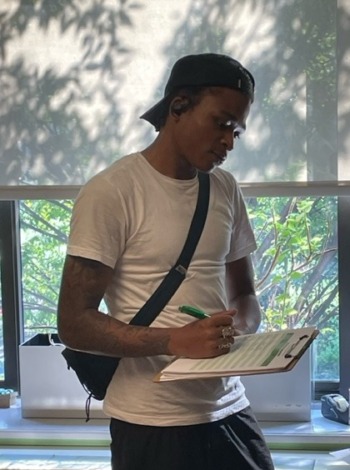

Isidoro Rodriguez/For Youth Today

Malik Rainey completes paperwork at Avenues for Justice’s New York City office.

“He saved me,” Rainey said, of Brian Stanley, the advocate. “If I hadn’t gotten into this program, things could have gone way worse.”

Avenues helped Rainey win a youthful offender adjudication plea deal. Such deals give 14- to 19-year-olds with no prior convictions a chance to avoid having a criminal record. In exchange for his plea deal, the court ordered Rainey to spend 12 months studying for and earning a high school equivalency diploma, completing employment training, observing a strict curfew, and not doing crime or being arrested.

“I had to complete the program or go to jail,” Rainey said.

At Avenues, which is funded by philanthropic and private donations, volunteers and staffers provide computer-coding classes, art therapy sessions, academic tutoring, mental and behavioral health counseling, sex education, job placement, and lessons in resume writing, job interviewing and dressing for success.

“The goal is to allow these kids [the freedom] to fight their cases from the outside, build a good track record and show the court … the progress they have made to prove that they deserve a second chance,” said Stanley, also Rainey’s mentor.

“We give written reports and speak on the record at court appearances about what the youth has been doing — if they have been observing their curfew, attending and advancing through the required amount of programming — and generally making sure they stay on track.”

Fewer rearrests among youth in community-based diversion programs

Of roughly 1,200 13- to 17-year-old U.S. boys who were first-time offenders, 43% who’d participated in diversion programs akin to Avenues were rearrested over a five-year period ending in 2018, according to a study published in 2021 in Development and Psychopathology. By comparison, 66% of boys who were tried, convicted and incarcerated, instead of enrolled in diversion programs, were rearrested during the same period, researchers from Louisiana State, Arizona State and Temple Universities, and the University of California at Irvine found.

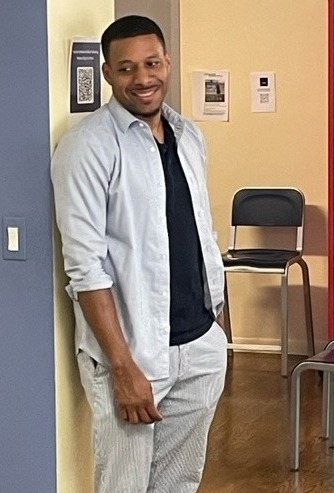

Isidoro Rodriguez/For Youth Today

Brian Stanley works directly with young people as an Avenues for Justice advocate.

In 2021, 6% of Avenues participants were reconvicted of a crime within three years of enrolling in the program, according to Avenues’ 2022 annual report. The Council of State Governments Justice Center has reported that up to 80% of youth who are incarcerated in some states around the country are rearrested within three years of release.

Courtroom advocates like Stanley are on the lookout for cases mainly involving youth and young adults with no prior convictions who, primarily, have been charged with non-violent offenses. They must be interested in turning their life around. Advocates confer with defense attorneys. They try to persuade prosecutors that diversion is better than time in detention for those youth whose charges include drug and gun possession, robbery, burglary, and, in some cases, even assault.

[Related: To end the age of incarceration, three communities pioneer a developmental approach]

“We have decades of research that demonstrate that community programs are not only just as good as locking kids up for public safety but are far, far better,” said Amy Fettig, deputy director of Fair and Just Prosecution.

“Outcomes are consistently better and these programs cost a fraction of what it costs to incarcerate children,” Fettig added. “We know what works. The problem is that these programs don’t get the funding that prisons, jails and juvenile detention centers do.”

Diversion cost less than juvenile detention

According to the National Institute of Corrections, 33 U.S. states or jurisdictions spend $100,000 or more annually to incarcerate youth. By comparison, diversion can cost approximately $75 a day per young person or roughly $27,375 per year.

“We have to think about how we fund these programs in a way that creates the kind of scale we need, so that we have an alternative and our knee-jerk reaction isn’t always more prisons more incarceration,” Fettig said.

In New York, Maryland and Minnesota, as examples, lawmakers have increased funding for diversion programs. Meanwhile, Nevada became the first in the nation to establish diversion courts statewide for at-risk adolescents with autism. Denver launched a program for teens caught with guns that connects them with mental health services, teaches them how gun violence affects a community, assigns them to do community service and requires them to meet with panels that include people impacted by their crimes.

[Related: From the mouth of babes: Letting young people lead us to a new vision of justice]

Since completing Avenues’ program, Rainey has gotten his high school equivalency, a driver’s license and a security guard’s job. He is pondering how to gain better-paying employment in construction, municipal sanitation or IT.

“I never even thought about college before this,” said Rainey, adding that he is considering enrolling. “Participating in the training and workshops kept me active, helped me grow and stay out of trouble. It changed my life.”

Even after Rainey and other Avenues enrollees complete court-mandated diversion activities, they still can avail themselves of Avenue’s guidance and services. Rainey continues to attend training programs at Avenues’ Harlem location, including courses for earning a New York State Career Development and Occupational Studies Commencement Credential certifying him for entry-level employment.

He also promotes the program to other youth who might benefit.

“People in my own neighborhood — younger than me, older than me or my age, whether they need help or not — I tell them about the program,” Rainey said. “It’s all about helping the next person.”

Diversion aims to help participants and the public

Currently, five Avenue participants are training to be plumbers and electricians through Building Skills New York, one of the employment partners with Avenue, which pays interns placed by those employers $15 an hour. The hope is that they’ll be hired full-time.

Stuart Cinema & Cafe in Brooklyn, as another example, hires Avenues participants as cooks, administrative assistants, ticket booth operators, and concession stand workers.

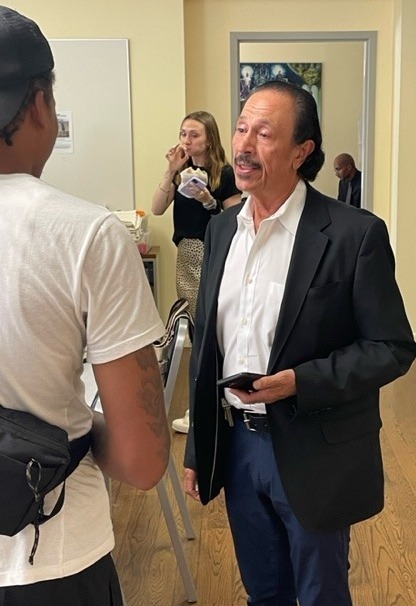

Isidoro Rodriguez/For Youth Today

Avenues for Justice executive director Angel Rodriguez speaks with program participants.

Avenues projects also include weekend seminars on civil rights, race history, social justice, and other topics that many participants know little about, said Angel Rodriguez, co-founder and executive director of Avenues.

“You hear every day that all these horrendous things have happened [because of youth offenders] and that kids need to be sent to jail or prison. And it’s sad that we only portray that negativity because it does a lot of damage,” Rodriguez said.

“So, we’re trying to make the public understand what’s really going on here, what we’re doing to change things. And we have a lot of kids who are doing a lot of really great things.”

Avenues’ program shows young people possibilities that many often feel aren’t available to them because of who they are and where they’re from, said Felicia Forster, business development representative at Building Skills, a nonprofit connecting underemployed populations to construction training and job opportunities

“Employers rule out people who’ve been involved in the justice system, so the first main hurdle for a lot of these kids is just knowing the opportunities exist and that if they don’t want to go the standard route of college, and want to jump into a trade like construction they can,” Forster said.

“This country,” Avenues’ Rodriguez said, “has to start looking at the common denominators that are getting us to this place … [W]hen the kid just ends up indicted and imprisoned for this jail time that these folks are asking for, the damage is done.”

***

Isidoro Rodriguez is a Brooklyn, New York-based reporter who covers police reform and misconduct, juvenile justice, gun violence, and sex work.