ST. GEORGE, UTAH — At the end of the two years he spent at a juvenile detention center in Ogden, Utah, Chase returned to his hometown with a high school diploma and 19.5 college credits, and a plan to earn a bachelor’s degree in business and manufacturing technology.

“I learned tools for life. I learned how to be an adult,” Chase, who asked to be identified only by his first name, said of the classes offered under Utah’s new Higher Education for Incarcerated Youth program. “Really, I learned to believe in myself again.”

He is thankful, said Chase, 18, of Ogden, for that program. Since its May 2022 launch, about 80 youth across Utah’s five long-term juvenile detention facilities have taken classes through the program.

Along with New Jersey and California, Utah is among a growing number of states that are implementing postsecondary programming for incarcerated youth. Utah’s Higher Education for Incarcerated Youth program even goes beyond what’s offered to incarcerated adults in Utah: Most adults in Utah prisons do not have access to free college-level courses.

Jennifer Rodriguez, executive director of the Youth Law Center in San Francisco said it’s hard to pin down exactly how many states offer postsecondary education to incarcerated youth in part because they are held in a variety of facilities — juvenile halls, camps, ranches, youth prisons, and adult jails and prisons.

“Every long-term youth facility should be rehabilitative in nature. That can’t happen if a facility only offers minimal education opportunities,” said David Domenici, executive director at Break Free Education, a nonprofit that develops and advocates for educational programming throughout criminal justice systems.

Young offenders often lag behind academically

Nationally, more than half of all incarcerated juveniles have reading and math skills far behind their peers. And incarcerated youth are identified as needing special education services — or already receiving services — at a rate four times higher than their peers.

About half of the Utah students in the program would not be considered “college-ready” at many institutions.

Hailly T.N. Korman, a partner at education consulting nonprofit Bellwether Education Partners, cautioned against pushing students into college courses before they’re ready.

“If these young people aren’t prepared for advanced course work, they may wind up with an F on their college transcript. They may also be spending down their PELL grant eligibility before they’re ready to work toward a degree,” she said.

Signs of positive impact

Utah’s Higher Education for Incarcerated Youth program, which is funded by an annual $300,000 state appropriation, lets participants study English, social sciences and math classes as well as personal finance, intro to economics, social ethics and other courses.

David Dudley/For Youth Today

Utah Rep. Lowry Snow in St. George, Utah.

To get college credit for college-level English, social sciences and math classes, students must first pass a screening test. Those who don’t pass can take the class for high school credit, said Nate Caplin, the program’s manager. Caplin, a lawyer who previously taught online classes for rural Utahns, proposed the idea for the program to Utah State Rep. Lowry Snow (R-St. George) in 2020.

At any point during the year, an average of 74 youth are incarcerated across Utah’s five long-term facilities. The average length of stay is about nine months.

Thus far, students in those college-level courses have earned about 539 credits in English, criminal justice, biology, political science, philosophy, art, economics and finance, and music, Caplin said. Classes are taught by professors from Utah Tech University, which oversees the program, and from Brigham Young University, Weber State University and Southern Utah University.

It’s too early to determine if that learning has helped those students released from detention find jobs, continue their education or avoid re-arrest. But there are signs that it’s having some positive impact, Caplin said: “One of our young scholars said that, for two hours a day, she forgets that she’s in prison.”

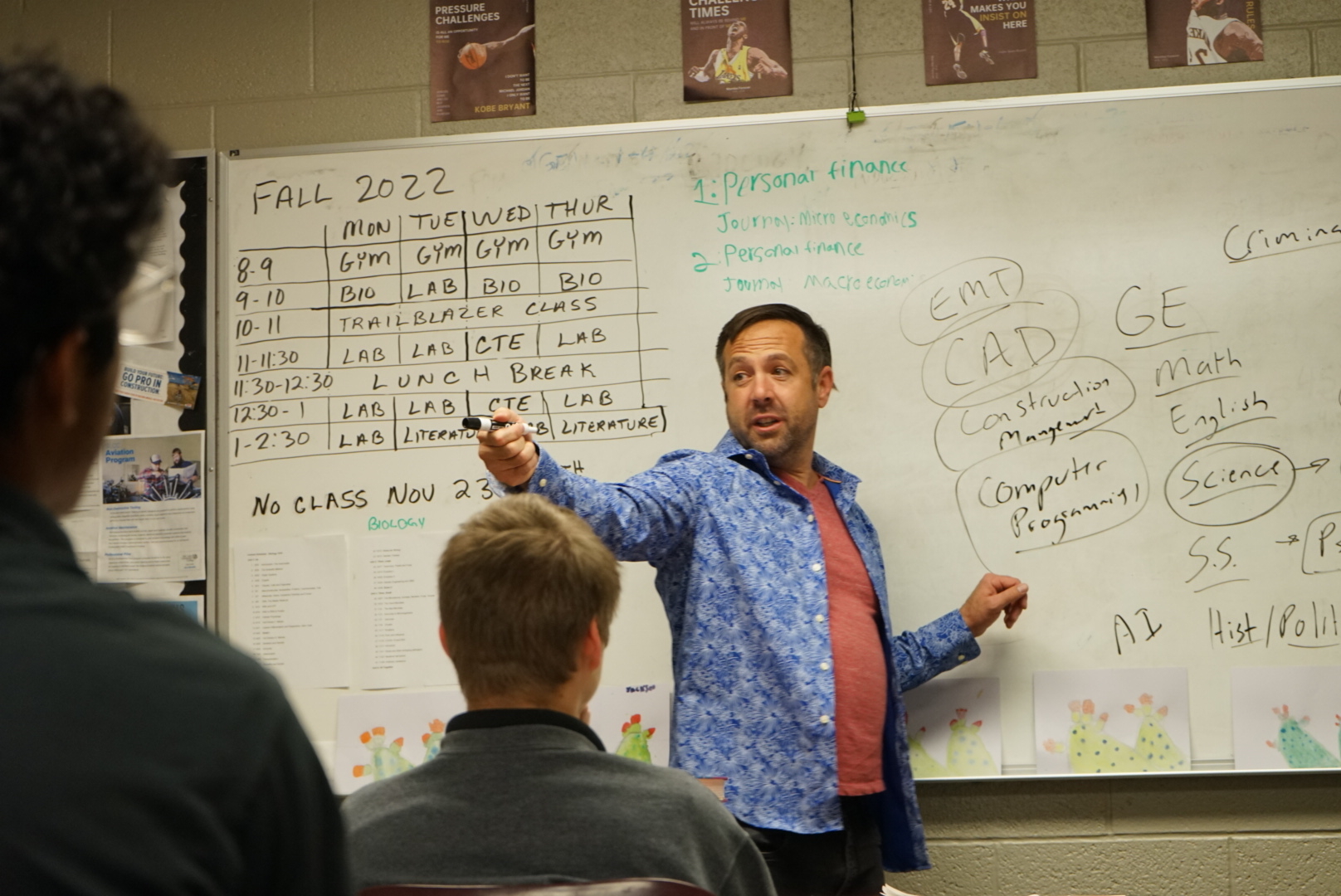

Joe Stewart, who teaches high school classes at Southwest Utah Youth Center in Cedar City, said the program allowed him to focus on students’ individual needs in core high school classes, while the professors teach their specialties.

“It’s lifted a great weight off of my shoulders,” he said.

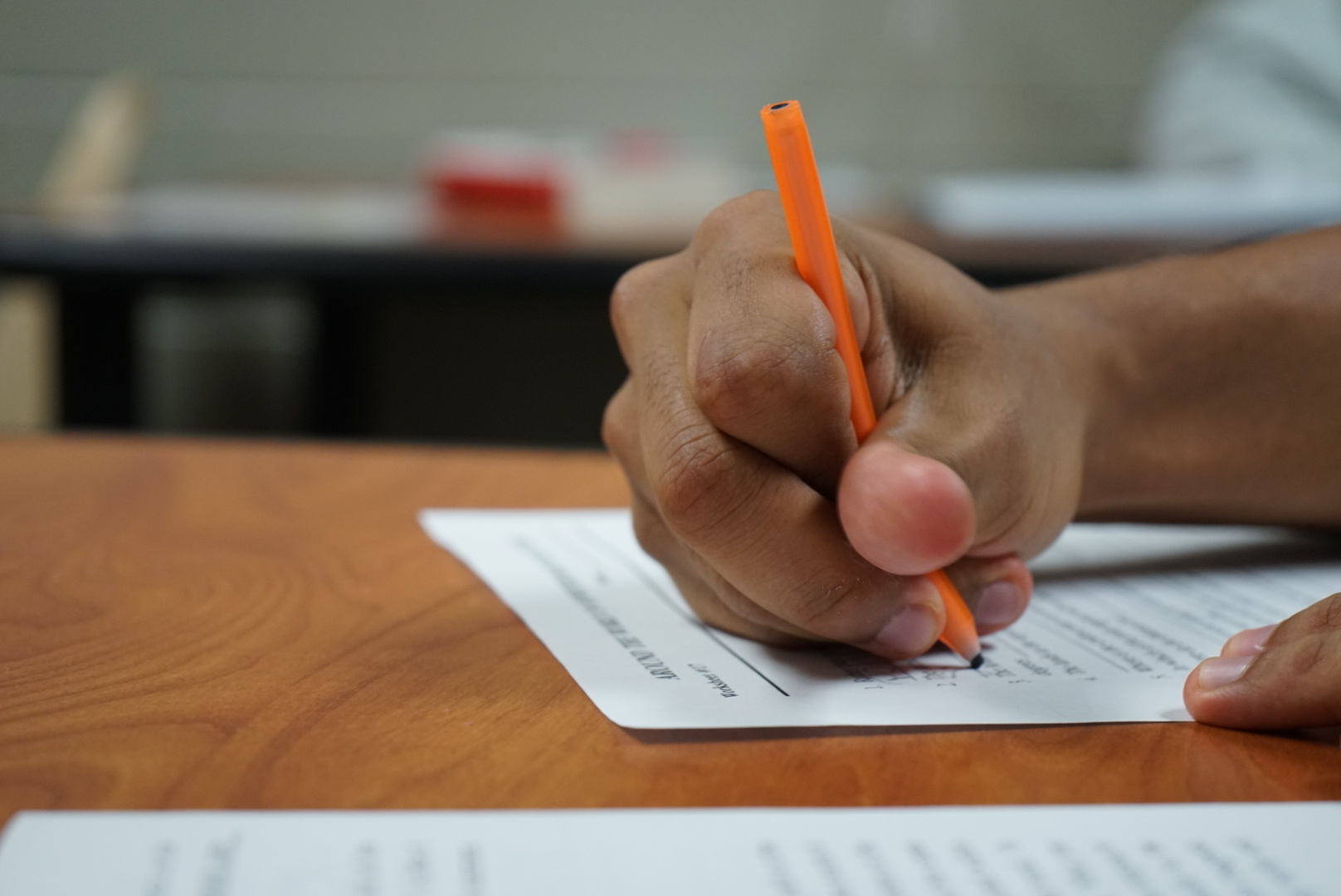

David Dudley/For Youth Today

A student uses a bendy pencil to complete an assignment at the Southwest Utah Youth Center in Cedar City, Utah.

“I didn’t think I was good enough”

Being incarcerated, said Chase, who spent those two years at Millcreek Youth Center, about three miles from home, made it easier to focus on his education.

“At home, I was distracted by getting high,” he said. “Millcreek gave me the structure I needed to be a good student.”

For Chase, education offered an escape from his own inner voices. “I always wanted to attend college, but I didn’t think I was good enough,” he said.

After earning his high school diploma at Millcreek, he began taking college courses through the Higher Education for Incarcerated Youth program and, through a separate program at the facility, training to become a welder.

He took English, finance and art, among other courses, mostly online.

David Dudley/For Youth Today

An incarcerated student works on an assignment at the Southwest Utah Youth Center in Cedar City, Utah.

For most classes, Chase and up to 15 other students sat in front of their Chromebooks in a Millcreek classroom as staff monitored to ensure that no one accessed materials that facility officials deem inappropriate.

“That made research challenging,” he said. “But we had facilitators who would print off materials that we needed.”

And because students aren’t allowed to take the laptops to their cells, they had an extra hour or two per day to finish their online homework in the classroom, said Chase, whose favorite class was philosophy.

“I loved learning about Viktor Frankl and Martin Luther King Jr.,” he said. “But my favorite is Aristotle.”

Credits earned through the program can be transferred to most public U.S. colleges and universities, Caplin said. And students who are released in the middle of the semester can finish their class via Zoom, as long as they have internet and computer access. Caplin also is working to secure scholarships for students to complete their degrees after they’re released.

Weber State University has awarded a scholarship to Chase and accepted the credits he earned at Millcreek.

“I think I can do it”

Southern Utah University English, writing and literature professor Julia Combs teaches English 1010 to boys at the Southwest Utah Youth Center in Cedar City. She accepted the position, initially, to earn money during a summer when she wasn’t teaching at the university.

“It wound up being the most rewarding work I’ve done in 25 years,” Combs said.

She recalled one student whose screening test indicated he was reading at a third-grade level.

“I tried to teach sentence structure to him,” she added. “I said ‘always use a subject and a verb’ — but he didn’t know what a verb was. But he’s reading ‘Percy Jackson.’ He knows all the Greek gods. That made no sense to me.”

Combs asked her students to write a personal essay answering “What does a perfect day look like to you?” But their project was interrupted when one student tried to sneak a laptop into his cell, violating program rules.

“They had to do their writing assignments with paper and bendy pencils,” Combs said. Regular wooden pencils are banned because they can be used as weapons..

Those bendable pencils put calluses on his fingers, said Dom, a student who studied with Combs while serving a 12- to 18-month sentence, and asked to be identified only by his first name.

But he benefited greatly from the program, said Dom, who hopes his soccer skills will earn him a college scholarship. He’s not sure what field of study he will pursue but he is pondering his options.

“Before coming here, I didn’t think about it that much,” he said in an interview at Southwest Utah Youth Center. “Since I started taking these classes, I’d like to become a doctor or a dentist. I think I can do it.”

***

David Dudley is a journalist, educator, and playwright based in southern Utah. He’s written for The Guardian, High Country News, the Christian Science Monitor, and other publications. His work has earned multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists in the Rocky Mountain region. David is a 2021-2022 John Jay/ Arnold Ventures Justice Reporting Fellow.