Growing up in arid Santa Paula, California, an oil town filled with citrus groves, Fabiola Gomez Flores had tricks for dodging the heat. Like many people she knew, her family lived in an apartment without air conditioning, so sometimes, on the hottest days, they would buy a ticket to the movies and cool off in the theater.

Along California’s Central Coast, coping with heat has always been a part of life, and temperatures are only increasing due to human-driven climate change. Towns in Ventura County saw record triple-digit temperatures this year.

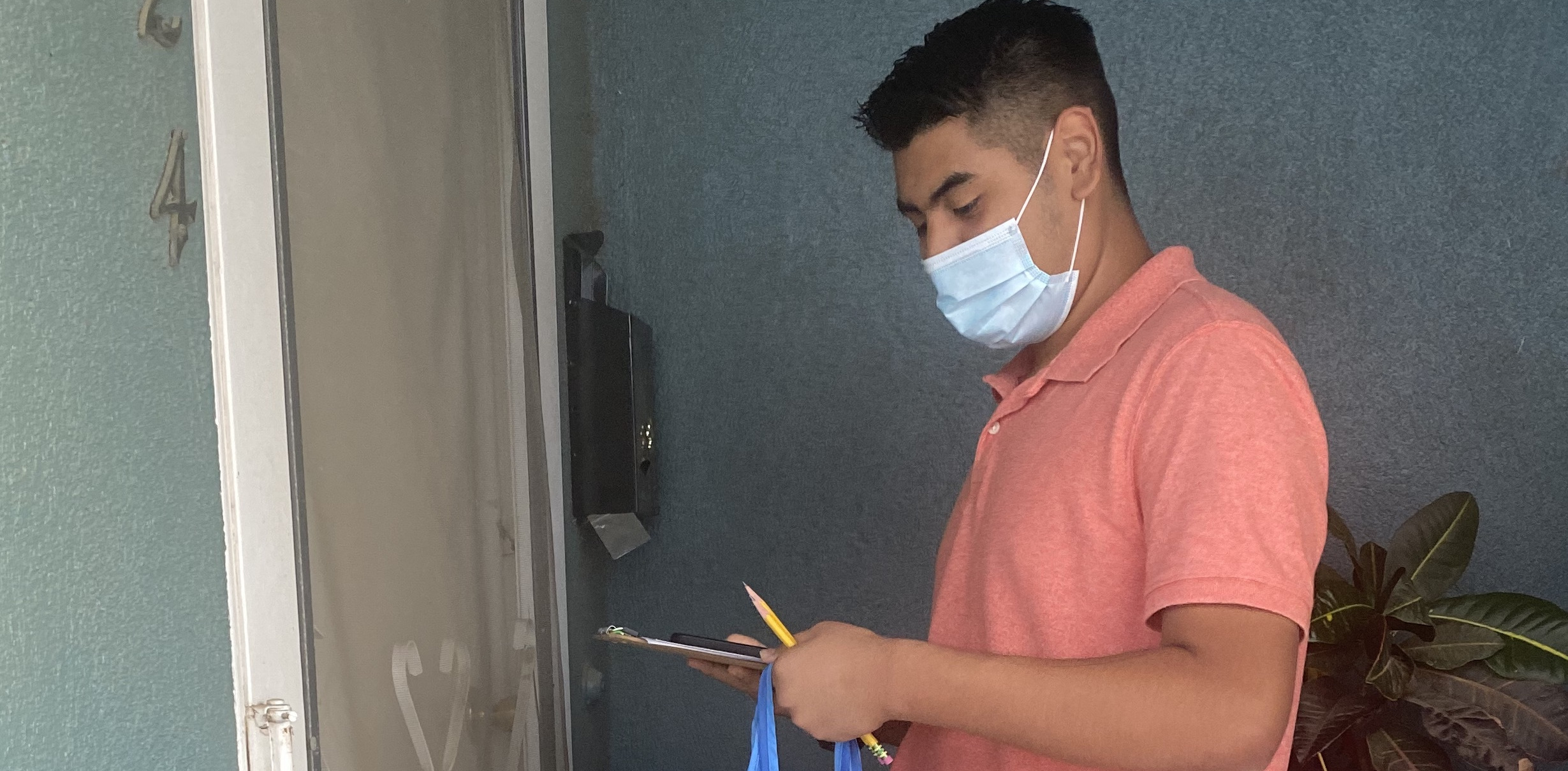

So when Flores, 25, a community organizer with Central Coastal Alliance United for A Sustainable Economy (CAUSE), heard from students over the summer that many classrooms at her alma mater, Santa Paula High School, lacked air conditioning amid the extreme heat, it seemed like the right time to take action.

“It made me feel like, okay, we need to investigate more on which classes do or don’t have AC and how the students feel about it,” Flores said.

Under her leadership, CAUSE members, including three youth fellows, designed a survey inquiring about access to air conditioning, fans and drinking water at the school, and how the heat impacted their ability to concentrate.

Soon, the project expanded into a community-wide survey of hundreds of residents, students and farmworkers who weighed in on how heat was impacting their health, safety and quality of life.

Across the country, young people are banding together to undertake similar surveys and create heat maps that capture their communities’ desire to mitigate and adapt to rising temperatures, which is helping to ensure that interventions are community-led rather than implemented top-down.

‘The area where students gather the most was the hottest’

Courtesy of CAUSE

Fabiola Gomez Flores, center, and other CAUSE members propose locations at Santa Paula High School that would benefit from shade and hydration stations.

In Santa Paula, the student survey inspired CAUSE members to find out how other vulnerable people living in Ventura County were experiencing the record temperatures.

Together, they brainstormed questions for residents of Santa Paula, including those tailored for farmworkers, some 36,000 of whom work in the county. In total, the CAUSE fellows collected over 360 surveys.

Brandon Martinez, a sophomore at Santa Paula High School and summer youth fellow with CAUSE, said the team wanted to find out how the heat was impacting community members’ health, and what people living in the city thought elected officials should do to improve conditions.

When he began his fellowship, Martinez said he didn’t fully realize how extreme heat made life difficult for his friends and neighbors. He was particularly struck by how much farmworkers are disproportionately impacted by the heat.

“Most of the farmworkers don’t get enough breaks … sometimes they’re not given water, [and] they also don’t have shade,” Martinez said.

The findings struck close to home. Martinez’s parents used to be farm workers, and nearly all of his friends’ parents currently work in agriculture, planting and harvesting strawberries, lemons, avocados and other crops.

Those surveyed had strong reactions to the questions, Martinez said. It seemed like the burden of heat “was really in their chest, and they just wanted to get it out,” he said.

“Most of these communities, they want to say their opinion but they’re ignored or not heard from the people in power like the government, or the city, or the school,” Martinez said.

“It really changed [our] perspective … hearing the public mention how it’s not just about AC but also about public areas with more greenspace,” Flores said.

Santa Paula High School students, for instance, mentioned how little shade they had access to during lunch, and how they wanted more trees and plants to take shelter under.

Young people across the United States are involved with many similar projects.

Shalae Clemens is a senior at McClintock High School, in Tempe, Arizona, and a Youth Climate Fellow with the school’s Neighborhood Justice Program. Over the summer, she helped develop a climate justice curriculum, including a lesson in which her classmates partnered with college students at Arizona State University’s design lab to measure temperatures around campus.

It turned out that what was known as the “senior lawn” — a cement and turf-covered area at the heart of campus where students ate lunch and celebrated homecoming — topped the infrared thermometers at 120 F.

“It was definitely ironic that the area where students gather the most was the hottest,” Clemens said.

As part of the program, students also brainstormed solutions, such as installing covered walkways and planting shade trees. Next semester, they’ll be planting a native garden with edible plants grown from indigenous seed banks.

“It really ties back into the intersectionality of it all, how it is underprivileged communities who are the most affected by climate change,” Clemens said. At her school, more than 65% of students are people of color and nearly 20% qualify for free lunch.

“[We’re] just trying to reverse those effects a little bit, within the population of our campus at least, by trying to provide some of those food resources,” she said.

Engaging and empowering communities through youth

Theodore Lim is a professor of urban affairs and planning at Virginia Tech and the co-author of a study on community-engaged heat resilience planning published in October in the journal Landscape and Urban Planning. For that study, Lim designed a two-week, summer STEM curriculum for 12- to 14-year-olds, enrolling nearly 80 students in summer 2021 in lessons that involved interviewing classmates, using mapping technologies to hypothesize temperature differences, and designing heat resilience networks.

At first, Lim said, students understood heat as a phenomenon well out of their control.

Related Stories

• Campus divestment movement targets schools, nonprofit status

• ‘Every day was a bad day’: Children working in agriculture aren’t protected equally

• For youth activists, historic climate law is only the beginning

• Electrical workers union trains Chicago youth for growing solar market

• After a win for U.S. climate change education, classroom implementation is off to a slow start

• Youth find hope restoring Rio Grande wetlands threatened by climate change

• Youth and climate change: How a generation is adapting while fighting for their future

“A lot of people honestly do not think of heat as the first thing that needs to be addressed,” Lim said, in spite of the fact that heat-related illness, which is preventable, is the leading cause of extreme weather-related death in the U.S.

By the end of the program, students reported a new understanding of heat as a problem stemming from public policy decisions that have shaped the built environment. Rather than describing high temperatures as something happening to them, they noted an awareness of a variety of urban planning interventions.

“It’s actually about having people make those connections and feel empowered to make a change in their own neighborhood,” Lim said.

Research led by or involving youth is essential to equitable responses to the climate crisis because young people are some of the major users of public spaces in cities, he added.

“They’re also important because youth are like a vehicle,” Lim said. “You engage youth, and you also start to engage their families, so there’s kind of this diffusion effect.”

Youth leadership is also significant for political reasons. “It gets eyeballs on the topic,” Lim said.

Coordinating with local officials on implementation

Back in Santa Paula, members of CAUSE are now taking a critical next step: discussing their heat survey results with the public in hopes of implementing solutions.

“It’s not just info that we’re gathering, we want [those in power] to see it and acknowledge it,” Flores said.

CAUSE members and residents who were surveyed by student fellows met with city and school district officials in October to present some of their most pertinent findings. They highlighted popular sentiments such as the desire for native sycamores to be planted where non-native eucalyptus trees were removed earlier this year, and identified three city parks in need of more robust tree canopies.

Students also used maps to show elected officials the places on their campus that lack access to water fountains, or where fountains are broken or needed maintenance, and proposed 10 sites where new hydration stations should be installed. They conveyed students’ desire for more shade, ideally from trees, outside of the library and center court area.

Next, students say they are planning to collaborate with elected officials to seek funding for these climate resilience improvements. City and district officials did not respond to requests for comment.

“It’s getting worse and better at the same time,” Flores said. “It’s getting hotter, but there’s more people that are aware of the situation.”

***

Leanna First-Arai is an educator and freelance journalist who covers climate and environmental justice.